Germany faces a glum outlook in 2017, writes Constanze Stelzenmüller. Many disappointed American liberals see it as the last bastion of liberal democracy, but there is real reason to fear a protest vote in the national election next fall. This piece originally appeared on the Washington Post.

Torn between impatience for 2016 to be over already and dread of what might come in 2017? Roger that, America. In fact, if there’s one nation in Europe that feels the same way, it’s my country, Germany.

Across the West, 2016 saw disasters, wars, roiling election campaigns, faltering governments, ruthless meddling by foreign powers, and surging populism fueled by anger, fear and the corrosion of trust in public institutions. A harsh and violent year by any measure. On top of it all, David Bowie and Leonard Cohen died.

Compared to the turmoil in Turkey, or the United States’ raucous election season, Germany seemed an island of (relative) social harmony and security for most of the year. Until December 18, when Tunisian Anis Amri rammed a Polish hAaulage truck into a bustling Christmas market on Breitscheidplatz in the heart of Berlin, killing 12 people and wounding nearly 50 others. That day, Germany joined the ranks of other Western nations that have seen major Islamist terrorist attacks: the United States, Spain, England, Belgium, France.

The attack itself is not a turning point. It was not Germany’s first terrorist incident, and attacks in other countries have claimed more lives. The calm, even sarcastic reactions of ordinary Berliners suggest that people are refusing to be intimidated. The authorities, from the police to Chancellor Angela Merkel, have behaved steadfastly and professionally. It was always understood that Germany was not likely to remain exempt from Islamist terrorism. Not least because its welcoming of Syrian refugees has been a slap in the face for the Islamic State’s false narrative of victimization by the West.

The larger significance of the Berlin attack lies in the fact that it is only the latest instance this year of events puncturing central aspects of Germany’s postwar narrative of itself—something the German journalist Andreas Rinke pointed out recently. He calls them Lebenslügen—life-lies—but that is too harsh. Germany’s 20th-century history of war, genocide, crimes against humanity, fascism, communism, and nearly 50 years of partition gave Germans good reasons to construct their postwar republic on the basis of firm founding principles of separation of powers, protection of minorities, rule of law at home, plus a commitment to Europe and Western alliances abroad. But Rinke is absolutely correct in saying that these foundations were under fire in 2016 like never before.

Postwar (West) Germany cultivated a special relationship with its Western neighbor, France, based on atonement and reconciliation; this hard-won friendship became the motor of Europe. Later, Germany bent over backward to do the same with its eastern neighbor, Poland. But today, France is preoccupied with a deep reform malaise and the rise of the right-wing Front National. And an authoritarian Polish government looks askance at Berlin’s overtures.

As a country that sits at the heart of the continent, shares borders with nine nations and trades with all of Europe, it was only logical for Germany to pursue ever deeper integration of the European Union. This year’s Brexit vote brought those hopes to a shuddering, gasping halt. London was a key ally for Berlin on free trade. That relationship is now badly damaged, too.

True, Germany has done a lot for the European Union: It held together the sanctions against Russia, at no small cost to German business. It faced down the euro crisis, and took on a massive migrant influx almost on its own. Yet it also bred resentment, with unilateral decisions that affected neighbors (such as opening its doors to the refugees), or its high-handed treatment of Greece. If Berlin is more lonely today, that is partly its own fault.

Germany’s hardwired preference for dialogue in foreign policy took a knocking this year as well. In Syria, it tried to support peace talks—to no avail. It took the lead in brokering the Minsk II agreement between Russia and Ukraine in 2014, and volunteered for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe chair in 2016. But at best, it achieved a freezing of the status quo, while violence in the Donbass region continues. It is now scrambling to reinvest in deterrence and defense.

Germany’s other lodestar was the United States. That bred a relationship of co-dependency that was equally cozy and resentful, and let Germany free-ride on U.S. security. Berlin has recently attempted to become a more responsible, capable and strategic partner. It seems the incoming president will be far less appreciative of this development than President Obama was. Donald Trump has rejected free trade, globalization, international law—all essential to Germany’s relations with the world.

[T]here is real reason to fear a protest vote in the national election next fall.

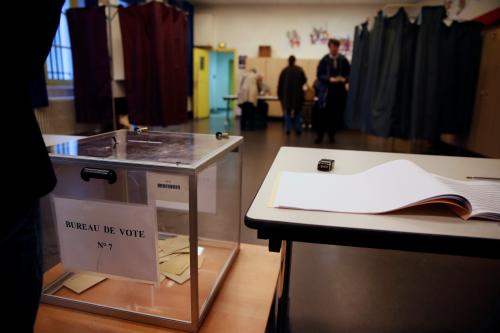

2016 was also the year that punctured complacency about the superior excellence of our democracy. Yes, my country is still doing a magnificent job integrating hundreds of thousands of refugees. It is responding to the Berlin attack by giving domestic security more muscle. But our own right-wing populist party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) now sits in 10 out of 16 state legislatures, and polls nationwide at 13 percent.

All this makes for a glum outlook for Germany in 2017. Many disappointed American liberals see us as the last bastion of liberal democracy. Thanks, but there is real reason to fear a protest vote in the national election next fall (the date is not yet set). Our intelligence services have warned of Russian intentions to meddle. Helpfully, the American alt-right appears to be taking a keen interest as well.

Small wonder Merkel hesitated before announcing that she would run for a fourth term in 2017. One thing is for sure: She, and ordinary Germans, can’t be (in the words of David Bowie’s most famous Berlin song) “heroes forever and ever.” We could use some luck. Or some friends.

Commentary

2017 is not looking so good for Germany

January 4, 2017