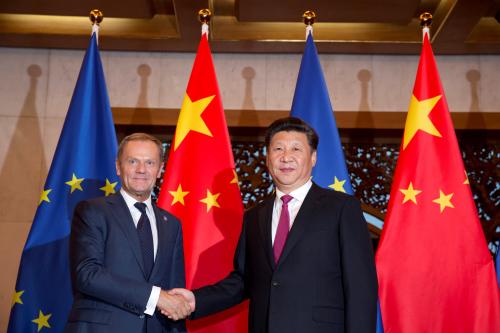

On both sides of the Atlantic, governments have been discussing separate bilateral investment treaties with China, write Philippe Le Corre and Jonathan Pollack. But without a more coordinated strategy between the EU and the United States, mounting dissatisfaction will continue to rise. This article originally appeared in Nikkei Asian Review.

The election of Donald Trump has led to widespread speculation about what the U.S. president-elect wants to do with and about China. Will he impose high tariffs on Chinese imports if Beijing doesn’t “behave,” potentially triggering retaliation? Will he strike a deal with President Xi Jinping on freedom of navigation in the South China Sea? Will he reduce the American military presence in Asia or might he increase it?

There are many questions, but few answers. Trump’s unexpected, taboo-breaking phone conversation with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen on December 3 has led to even more speculation, as well as dismay, in Beijing which considers Taiwan a renegade province.

One thing for sure is that Trump has no choice but to recognize China’s global rise. Over the past few years, the country’s global economic footprint has grown ever greater and more visible. As the world’s second-largest economy and the prime engine of global economic growth, China will soon mark 15 years of membership in the World Trade Organization.

Trump has no choice but to recognize China’s global rise.

China’s gross domestic product increased to $10.86 trillion from $1.33 trillion between 2001 and 2015. It is now the EU’s and America’s second-largest commercial partner. China is also now the second-largest source of outward foreign direct investment worldwide.

Officials and experts on both sides of the Atlantic wonder about China’s economic intentions, and Trump and other political leaders are contemplating how to deal with this increasingly important player. On December 2, U.S. President Barack Obama blocked China’s Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund from completing its 676 million euro ($714 million) buyout of German chipmaker Aixtron following a review by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States which found the deal posed a risk to national security. Fujian Grand in turn dropped its bid on Thursday.

Washington’s move, which was based on Aixtron’s U.S. subsidiary, confirmed Berlin’s own worries about the acquisition of sensitive technologies by Chinese companies. Amid concerns about sensitive data and technologies, the German Ministry of Economics in late October withdrew its previously issued approval of the sale of Aixtron. German political and business circles had been engaged in an intense debate over Chinese buyouts of high-tech companies since the 4.5 billion euro acquisition earlier in the year by Midea Group of Kuka, a cutting-edge robotics manufacturer.

The United States and Europe have become recipients of substantial Chinese investment. According to New York-based consultancy Rhodium Group, Chinese direct investment in the United States totaled $80.9 billion for 2000-2016. By comparison, data provider Dealogic tracked $90.1 billion worth of announced Chinese acquisitions in Europe in just the first 10 months of this year, boosted by China National Chemical’s $43 billion offer for Swiss agro-business group Syngenta. Chinese state-owned enterprises have also taken substantial stakes in European energy, port and airport infrastructure, including China Ocean Shipping Group’s purchase of a two-thirds interest in Athens’ Piraeus Harbor.

Limited access

The EU and U.S. chambers of commerce in China have been calling increased attention to the growing difficulties of their members’ gaining market access in fields ranging from construction to insurance and many high-tech sectors.

Amid these complaints, foreign investment in China is declining. But Chinese companies continue to undertake massive overseas investment, though officials recently indicated that large acquisitions will be scrutinized more closely in a move to reduce currency outflows.

Beijing’s long-term strategy, “Made in China 2025,” explicitly encourages major enterprises, especially state-owned companies, to acquire foreign technologies and brands to feed the country’s economic engine. These companies have encountered few obstacles, especially on the European continent, where cash-starved governments have welcomed investment offers.

The official Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States however has identified potential national security risks involving a number of planned Chinese investments in the United States. A $3.3 billion buyout of a U.S. lighting unit belonging to Dutch manufacturer Philips by a Chinese-led consortium was blocked in January. Other Chinese bidders have, like Fujian Grand, pulled back in the face of official opposition. Tsinghua Unigroup withdrew a planned $3.8 billion investment in data storage company Western Digital after CFIUS flagged the deal for review.

A lack of transparency has been an additional complication. Early this year, China’s Anbang Insurance Group decided to give up a $14 billion bid for Starwood Hotels after Wall Street analysts began to question the company’s ownership structure and ties to the Chinese state.

After years of opening their doors to Chinese investors, Europeans have also started a debate about how to protect national brands, especially in the IT sector. In the U.K., Prime Minister Theresa May stunned China by deferring approval of the planned 18 billion pound ($22 billion) construction of Hinkley Point nuclear power plant. The project was to be financed by China General Nuclear Power, with the backing of Chinese sovereign wealth funds.

In the end, London reaffirmed the original agreement, but the government insisted, “There will be reforms to the government’s approach to the ownership and control of critical infrastructure to ensure that the full implications of foreign ownership are scrutinized for the purposes of national security.”

On both sides of the Atlantic, governments have been discussing separate bilateral investment treaties with China. With a new U.S. administration about to take office, there is little chance an agreement will be signed in the coming months. Despite widespread talk this year in the EU of a “Sino-European strategic partnership,” negotiations here too have made slow progress.

The lack of reciprocity between China, the United States, and other major economies is worrisome. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission recommended last month that Washington consider limiting acquisitions by state-owned enterprises from countries with which the Untied States does not have a bilateral investment treaty.

Continental disgruntlement

European politicians are also speaking out. Before visiting China in November, Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s vice chancellor and minister of economics, asked his ministry to prepare proposals for giving EU institutions greater power to block takeovers in strategic industries by companies from outside the bloc. The next French government is also likely to look into this issue.

Ideally, the EU would agree on a mechanism to protect industrial and technological assets, but getting its 28 members to do this will be challenging. A more promising approach would be to establish domestic agencies to scrutinize inward foreign investment in each recipient country. But a much more serious and sustained transatlantic dialogue on managing China’s global economic rise seems long overdue.

Without a more coordinated strategy between the EU and the United States, mounting dissatisfaction will continue to rise. The new U.S. administration and next year’s incoming crop of European leaders need to engage much more fully on common challenges. Major issues, including investment, cybersecurity and China’s market economy status, seem appropriate places to begin.

Commentary

The U.S. and EU both want to trade with China—But they shouldn’t go it alone

December 15, 2016