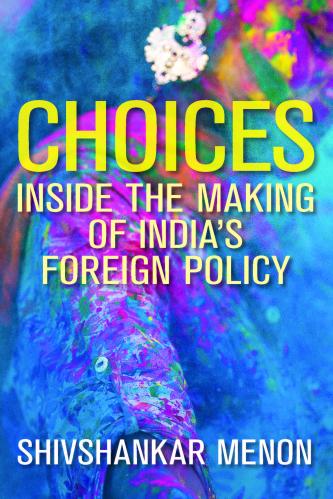

A unique experience in a classroom last year caused me to write a new book, titled “Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy.”

I was leading a study group on Indian foreign policy at Harvard, where one session was devoted to India-Pakistan relations. We naturally discussed cross-border terrorism and the 2008 Mumbai attack. After my customary presentation outlining the issues, the first student to speak said he had lost his father in the attack. From that point on, there was an animated discussion among a group of students from countries around the world—from Argentina to Uzbekistan to India and to China—expressing diverse points of view. The discussion went on well beyond the two hours allotted and seemed to have struck a chord among many of the students, no matter where they were from.

Indeed, as the dialogue in that classroom helped illuminate, choice is the essence of government. These choices are not only about winning or losing, being right or wrong, knowing true from false, or other binary choices. They are choices made in the fog of events, with imperfect knowledge and limited foresight into consequences. Often the policymaker finds himself “mini-maxing,” minimizing harm and maximizing gain, or balancing off different interests and considerations.

“Choices” is an attempt to describe that process, through five examples of choices the Indian government made while I was lucky enough to be a participant in that decisionmaking.

The choices I highlight relate to:

- The 1993 border peace and tranquility agreement between India and China, when both countries agreed—despite having the world’s largest boundary dispute, and having fought a war over it less than 30 years prior—to respect the status quo while they negotiated the boundary and developed the rest of their relationship;

- The Civil Nuclear Cooperation Agreement between India and the United States in 2008—also known as the 123 Agreement—which removed a long-standing obstacle and transformed the relationship

- The Indian decision not to use overt force against Pakistan in 2008, despite conclusive evidence that the terrorists who attacked Mumbai came from Pakistan and were trained by elements of the Pakistan Army intelligence agency (the ISI). I think that another Mumbai-type attack would evoke a different Indian response, and that any government of India would likely have to be seen to use force;

- The final months of the Sri Lankan civil war in 2009, which eliminated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam as a fighting force and made India choose between its strategic, domestic political, and humanitarian interests; and

India’s doctrine of no-first-use of nuclear weapons—which I think is the right policy for India’s set of unique circumstances, but should continue to be regularly reviewed—which forced policymakers to wrestle with the difficult question: Why have a weapon and announce that you will not use it? To date, only India and China have announced such a policy. President Obama is reportedly considering it, however, and it is not surprising that many remain to be convinced of the policy’s utility.

I examine whether one can draw any conclusions about India’s behavior as a great power from the predilections that these and other choices reveal. I conclude, in effect, that India’s foreign policy and national security choices have been personality-driven, strategically bold but tactically cautious, marked by realism, and recognizably Indian (though this is hard to define). The role of the Indian prime minister in these decisions has always been most significant. International relations theory seems to underestimate the role of individuals, (while crime fiction overestimates it), even though choices are always made by people.

[C]hoices are always made by people.

To my mind, there does seem to be an Indian way of dealing with these issues. And the end result—in terms of the primary goal of transforming India into a modern, strong, and prosperous country—has been largely successful.

All in all, this is a practitioner’s book, not a theoretical understanding of India’s foreign policy, though you might argue that there are implicit theoretical and ideological assumptions in any such work. I leave that to others to discover and comment on.

It was only after writing the book that I realized how China runs right through it. China is today a significant factor in every one of India’s major relationships and in most aspects of Indian policy.

The utility of force and diplomacy is another theme that runs through the book, relating to Pakistan and cross-border terrorism, and to Sri Lanka in 2009, and to the use of nuclear weapons.

The book also raises, but does not attempt to definitively answer, several questions which came up in the course of looking at these choices. The morality of choices in foreign policy is one aspect that I think deserves to be further examined. Does national interest or national development justify all means and all acts of state? What makes one choice ethical and not another? It is justified to kill one person to save many? My attempt when writing the book was to follow the historian’s rule: to respect the evidence, and to separate one’s own perceptions from facts and analysis. This is not easy to do. Only the reader can judge whether the attempt has been successful.

Finally, what kind of power will India be? We live today in an age of ultra-nationalism all around us, within India and abroad. I personally consider this dangerous, for it collects the tinder for a new conflagration, while denying leaders the flexibility to compromise and accommodate each other to keep the peace and concentrate on the real business of mankind, improving human welfare, and realizing our potential. Hence the continuing relevance of the quotation opening the last chapter from Gandhiji: “True power speaks softly; it has no reason to shout.” We forget that at our own peril.

Commentary

Inside the making of India’s foreign policy

October 31, 2016