The 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong brought over 100,000 city residents out to occupy busy thoroughfares. The movement deeply shook politics in the city, as well as relations with mainland China. And it reinvigorated a political reform process that—while bumpy and ultimately unsuccessful this time around—has the real potential to re-shape Hong Kong-Beijing relations moving forward.

In a new book, “Hong Kong in the Shadow of China: Living with the Leviathan,” Richard Bush—senior fellow and director of the Center for East Asia Policy Studies at Brookings—outlines how political compromise failed in the wake of the 2014 protest movement and why that matters for Hong Kong, mainland China, Taiwan, and the United States. Bush argues that the deep mistrust—not only between pro-Beijing (known as the “establishment”) and pro-democracy (referred to as “pan-democrats”) forces, but also within the democratic camp—caused political reform efforts to break down.

At an event at Brookings on October 4, Ambassador James Keith, former consul general of Hong Kong, provided remarks on the book and emphasized the importance of building political trust for the future of reform.

A politics explainer

While the Umbrella Movement was the most electrifying moment in Hong Kong’s struggle for democratic reform, it was only the middle chapter of a much longer story. In 1997, when Hong Kong’s sovereignty was returned to mainland China from Great Britain, the thriving economic hub that Beijing inherited was already becoming a deeply political city. Why? In his book, Bush points to economic inequality, for one: Due to globalization, technological change, and government policy, Hong Kong residents had unequal access to wealth, education, housing, and employment. That catalyzed demands for policy solutions.

Bush also posits that the “millenialization” of politics played a role. While mass demonstrations are not new in Hong Kong, this form of civic engagement has been dominated by young people in the last decade. The millennial generation in Hong Kong has faint memory of the process of reverting sovereignty to China in 1997. Instead, they are focused on the year 2047, when according to the Basic Law (Hong Kong’s mini-constitution), the “one country, two systems” governing model is set to expire. Gaining a greater say in the political system before this deadline has become a main priority for millennial leaders.

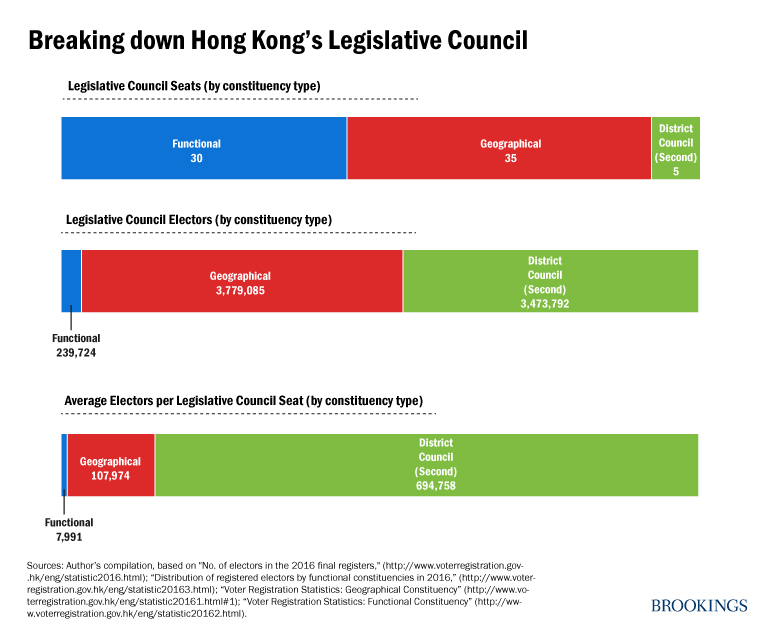

The final reason for the politicization of Hong Kong is China. During the negotiations with Britain prior to the handover of sovereignty, Beijing created a political hybrid for Hong Kong, what Bush terms a “liberal oligarchy” in his book. On the oligarchy side, Hong Kong’s political system fosters asymmetric concentration of power: Almost half of its Legislative Council seats are selected by a small group of functional constituencies who mostly represent business interests (and who are typically allied with Beijing). Even though Hong Kong citizens elect 40 members—for the geographical constituency and District Council (Second) seats—Beijing has been able to keep its allies in power and prevent pan-democrats from winning a majority. Moreover, Hong Kong still does not have competitive elections for the city’s leader, the chief executive, a fact that political reform meant to remedy.

On the liberal side, Beijing allowed the city to retain the political rights and rule of law established under British rule. China implemented the “one country, two systems” governing model (which Deng Xiaoping originally created for Taiwan) to guarantee these political and economic differences, while maintaining a one-party, Leninist system on the mainland. While the hybrid system allows Beijing to ensure that allies remain in control, Bush argues that the Hong Kong government’s April 2015 reform proposal did provide a narrow path for a pan-democratic candidate to pass the nomination screening process. That proposal would have empowered a nominating committee—similar to the election committee that currently picks the chief executive—to choose two or three candidates to face a popular vote. Therefore, if the democrats had been able to unify and nominate a moderate who was popular among Hong Kong residents (Bush notes that such people do exist), then the establishment camp and Beijing could not ignore such a candidate. This scenario would thus create a genuinely competitive election and a high likelihood that a pan-democrat could win.

.@RichardBushIII unpacks #HongKong's unique political system, democracy living in the #ShadowOfChina: https://t.co/T8CigFWiZ8 @BrookingsInst pic.twitter.com/gLQt37flV7

— Hunter Marston (@hmarston4) October 4, 2016

Is there a demonstration effect on Taiwan?

In his book, Bush examines what kind of demonstration effect the Umbrella Movement and greater political reform process has had on Taiwan. While Beijing hopes that “one country, two systems” could be used for Taiwan if cross-Strait unification ever happens, Taiwan remains reticent. The biggest reason is that “one country, two systems,” as implemented in Hong Kong, only provides a semi-democratic system, but Taiwan has had a full democracy for two decades. The prospect of decreased democratization does not sit well with Taiwan voters.

Ambassador Keith noted that “one country, two systems” was originally implemented to provide Hong Kong with the autonomy to thrive economically and support the mainland. But more recently, Hong Kong has had diminishing economic value for Beijing. This has altered the dynamic within their relationship: Instead of Beijing strengthening autonomy in Hong Kong to support Chinese growth, Hong Kong is now in a more defensive position, with many people fighting now just to protect their quality of life. This change in attitude, Keith argues, is not lost on Taiwan. When things worked well, Beijing liked to use Hong Kong as an example for how a territory can live with the mainland, but recently, Taiwan has viewed Hong Kong as an example of how one cannot live well with the mainland. Ultimately, the future of “one country, two systems” as implemented in Hong Kong will not only impact the city’s relationship with Beijing, but likely cross-Strait relations as well.

What’s next?

In the September 4 Legislative Council elections, 60 percent of all voters supported anti-establishment candidates and even elected six pro-independence “localist” candidates. Bush argues that the growing anti-Beijing sentiment, as these results demonstrate, leaves the mainland government with three options:

- Continue the status quo. In this option, “one country, two systems” will soldier on, but with Beijing increasing its economic and cultural influence in Hong Kong. This scenario, however, does not confront Hong Kong’s basic problems, and will likely lead to continued resentment by Hong Kong resident’s towards the mainland and its policies.

- Restrict political freedoms and legal order. This is the worst option, according to Bush, since it would directly threaten the foundation of “one country, two systems.” Recently, there have been signs that Beijing is in fact chipping away at the governing model, such as the illegal detention of Lee Bo, a small-time bookseller who published incendiary material about Chinese Communist Party leaders.

- Liberalize the political system to popularly elect leaders. This would be a surprise move by Beijing, but would be the first step to stabilizing Hong Kong’s governance. While it is unlikely Beijing will abandon the nominating committee system for the chief executive, it could instill reforms to make that process more competitive.

While Bush acknowledges that the third option, which he hopes Beijing will follow, would require the Chinese Communist Party to implement policies contrary to its self-interest, it could also foster greater stability in Hong Kong. Other problems certainly remain, but this would be a critical first step towards improving Hong Kong’s governance and tackling economic inequality challenges.

But a successful solution does not just rely on Beijing. Bush notes that democratic transitions work best when progressives in the regime work alongside moderates in the opposition to negotiate a transition pact. As Hong Kong politics become more polarized, it will be particularly important for the moderate, radical, and localist forces within the pan-democratic camp to find ways to unify.

Commentary

Looming large: The future of Hong Kong in the shadow of China

October 7, 2016