Editors’ Note: This post is based on a forthcoming book by Vanda Felbab-Brown titled “The Extinction Market: Wildlife Trafficking and How to Counter It.”

As the world celebrates World Wildlife Day on March 3, the planet is experiencing alarming levels of species loss—caused, in large part, by intensified poaching. Wildlife trafficking and its associated activities affect national and international security in a myriad of ways: They can provide support to criminal groups, increase risks of health epidemics, and further degrade the already fragile ecological systems on which humans depend. Efforts to combat wildlife trafficking, meanwhile, provide new opportunities for cooperation between the United States and China, among other countries.

Emptying forests, savannahs, and oceans

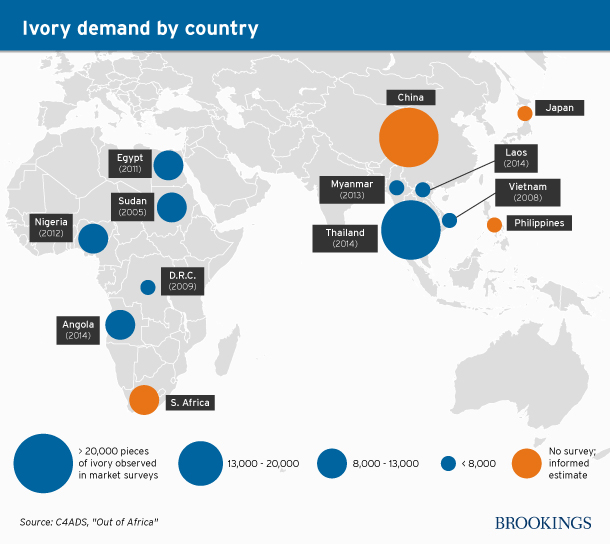

This unrelenting poaching crisis has been under way for well over a decade. It’s stimulated by the greatly expanding demand for animals, plants, and wildlife products particularly in China, East Asia, and among East Asian communities around the world. The crisis has been enabled by extensive and increasing corruption among park rangers and customs officials in many wildlife source countries, including in Southern and Eastern Africa and Southeast Asia. The problem has also been exacerbated by the complicity of local communities living near parks, and facilitated by the sheer scale of legal trade among which wildlife contraband hides. The growing firepower of poachers and desperation of policies adopted in response—such as to shoot poachers on sight—have multiplied the violence levels associated with poaching and wildlife trafficking.

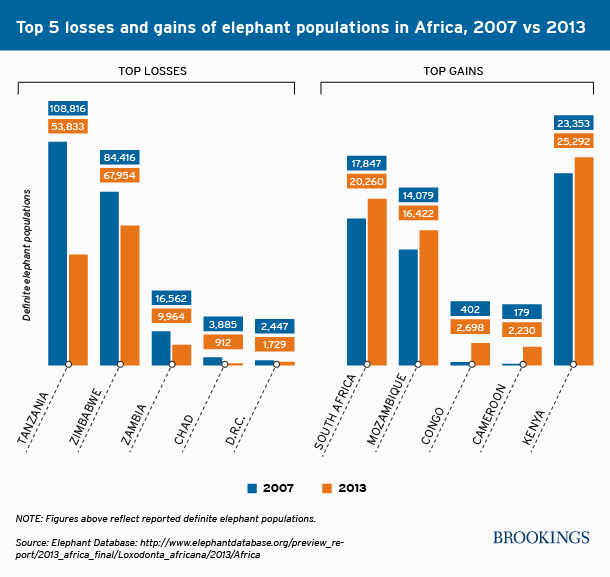

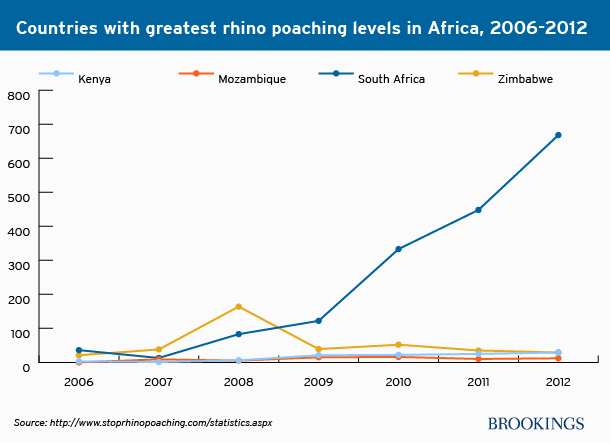

Elephants, rhinoceros, and tigers are being illegally slaughtered at massive rates. Beyond those iconic species, many other animals are captured, killed, and trafficked for trinkets, for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) substances, or for the global pet trade. In combination with habitat destruction and global warming, hunting and poaching might eliminate entire genera of species, further undermining remaining ecosystems.

Although East Asian countries—particularly China, Vietnam, and Thailand—are the key consumption and demand markets, the United States is widely believed to be the country with the second-largest consumer market for trafficked wildlife. But new demand (and supply) markets are once again rising in Latin America: Much illegal trade in parrots takes place in Brazil, for example, and many affluent Mexicans love boots made of snake skins. Demand also comes from other places often ignored in the story of the global slaughter, including in various East and West African countries (which are often described merely as source countries). Oceans are being emptied of creatures as well, be they sharks, tuna, sea cucumbers, or seahorses.

At our own risk

The rate of species extinction, now as much as 1,000 times the historical average—and the worst since the dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago—deserves to be seen, like climate change, as a global ecological catastrophe. It merits high-level policy initiatives to address its human causes.

In addition to irretrievable biodiversity loss and economic losses due to ecosystem degradation, wildlife trafficking also poses serious threats to public health. Diseases linked to wildlife trafficking and consumption of wild animals have included SARS and Ebola. Wildlife trafficking could thus be the trigger of a global pandemic.

Wildlife trafficking can also support other forms of organized crime and fuels violent conflict, though the links are often exaggerated. Militancy represents just a sliver of wildlife trafficking.

Thai highway police officers look at a tiger’s skin confiscated from smugglers at an unknown location in Thailand . Credit: Reuters/Wildaid.

Could ivory laundering soon be ended?

At this moment of acute crisis, wildlife trafficking is attaining unprecedented policy attention. The United Nations Security Council has discussed how to stop wildlife trafficking, and the goal of eliminating the problem was incorporated into the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Wildlife trafficking has also been an important subject in the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal. The governments of the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany have increased spending on combating wildlife trafficking around the world, expanding the menu of the diplomatic and law enforcement efforts, as well as plans to provide alternative livelihoods and reduce demand.

Perhaps most important, the United States and China have committed themselves to fighting global poaching. The United States has tightened many of its own rules, trying to close loopholes for the laundering of trafficked wildlife. For years, indifferent and even outright complicit in global wildlife trafficking, Chinese law enforcement agencies have confiscated and crushed illegal ivory and seized other illegal wildlife products—such as rhino horn and Asian black bear paws—in several raids. (However, systematic enforcement of wildlife regulations is not yet frequent or a priority for Chinese authorities.)

Crucially, after years of international lobbying, China promised in 2015 to declare illegal its official market for ivory, which had been a crucial driver of elephant poaching and a facilitator of ivory laundering. China has not said when this will take effect, but there is a widespread expectation that the market will be prohibited by the end of 2016. In January 2016, Hong Kong’s leader, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, followed China’s example and announced that Hong Kong, too, will totally ban the sale of ivory—once again without specifying when. The decision is still welcome, since Hong Kong has long served as perhaps the major hub of ivory carving and laundering.

Paradoxically, China’s economic downturn may be good for wildlife and conservation efforts: with less disposable income, wealthy and middle-class Chinese and East Asian consumers may spend less on wildlife luxury goods, giving animals around the world a breathing pause.

An animal carer feeds a baby female pangolin with liquified food from a syringe at Bangkok’s Dusit Zoo, one of several hundred mammals recently seized in raids by Thai police. Credit: Reuters.

Keeping wild things wild and abundant

It’s not enough to provide temporary reprieve, or to tighten the trade loopholes that allow laundering of ivory, rhino horn, geckos, and many other animals. Nor is it enough to simply beef-up interdiction, or even to vastly improve the economic alternatives to poaching in order to motivate local communities to buy in to conservation.

The bottom line is that demand for wildlife products must be reduced and kept low. To reduce demand, messaging campaigns should emphasize less altruistic appeals and long-term negative public goods consequence rather than the immediate personal costs of consuming wildlife. In particular, this includes stressing the negative effects to one’s health, such as emphasizing high mercury content in shark fins. Visible dramatic health consequences often were the mobilization core of other environmental campaigns, such as against acid rain and ozone depletion. Anti-poaching and anti-wildlife consumption campaigns should further seek not only to debunk the bogus purported benefits of consuming wildlife to one’s sexual life, such as that consuming rhino horn powder will enhance sexual prowess, but in fact emphasize the outright negative sexual effects—namely, that consuming wildlife products or having them in one’s possession will severely negatively affect the prospects for dating. This latter method has been effective in reducing cigarette and drug use. Moreover, campaigns to reduce demand for wildlife should focus on resistance to peer pressure and not rely on general awareness programs.

There is no silver bullet in policy to stop the bullets of poachers. Nor is there a one-shoe-fits-all design, and policy choices are highly contingent on specific settings. But that does not mean that we should give up the efforts to stop poaching. It is our moral imperative as well as in our own self-interest to do all we can to preserve the planet’s species and biodiversity.

Graphics created by Rachel Slattery.

Commentary

The global poaching vortex

March 2, 2016