Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

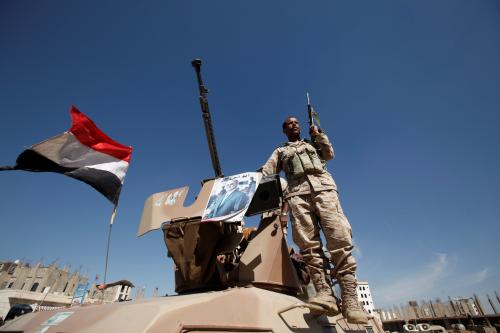

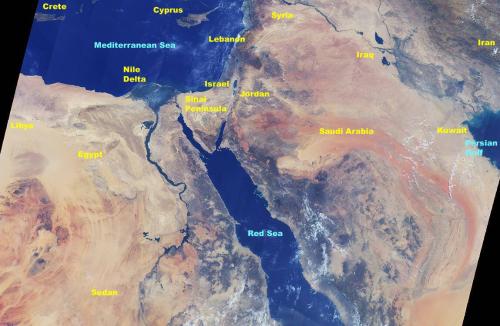

While Yemen was barely mentioned during President Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia last week, there is no doubt about its centrality to the U.S.-Saudi alliance. Trump warned against the Iranian threat to Yemen and the region. He also praised the Saudi-led coalition to fight the Houthis. The deaths of thousands of innocent Yemenis, however, were not mentioned once during Trump’s visit.

The $110 billion arms deals signed by Trump and King Salman is yet another example of the appalling lengths some will go to in order to benefit from a lucrative war business without acknowledging the death and destruction that such deals cause. These arms deals were initiated under the Obama administration, which later halted the deals following reports of violations by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. The Trump administration, on the other hand, sealed the deals in Riyadh last week.

The Saudi-led military coalition that has been fighting the Houthis and former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s allies in Yemen since 2015 has largely failed in its mission. The Houthis remain in control of many of the strategic parts of the country, including its capital Sanaa. Plans by the Saudi-led coalition to attack the highly strategic port of Hodeida would worsen an already bad situation—70 percent of food and aid was previously delivered via Hodeida. Following earlier attacks against the port, the delivery of such aid was significantly hampered and has contributed to the humanitarian crisis that has gripped the country. Moreover, the Houthis seem unfazed by attacks on Hodeida, where they receive many of their arms.

The argument for Saudi strategic military gains in Yemen to force the Houthis to the negotiating table thus no longer holds. More than 10,000 Yemenis have died, most of them innocent civilians, and millions are malnourished, starved, and have been displaced. The country is on the brink of famine and a cholera outbreak has recently gripped large swaths of the population.

Trump hailed the arms deals as “tremendous investments” that would create “jobs, jobs, jobs” for Americans. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson pointed to the importance of the deals in fighting “Iranian-related threats which exist on Saudi Arabia’s borders on all sides.” Nothing was said about the millions of victims of the war—and of the arms deals—who continue to suffer.

UNICEF estimates that one Yemeni child dies from starvation every ten minutes. That means the lives of 6 Yemeni children ended during Trump and King Salman’s hour-long speeches last week.

The U.K. has also been cashing in on the war in Yemen since 2015 through its arms sales to Saudi Arabia, worth £3.3 billion. This despite repeated calls for a halt to the arms sales, particularly in light of mounting evidence of violations of international humanitarian law by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

While Yemen has long suffered from a water crisis and other environmental pressures, the war there does not stem from a faceless humanitarian crisis. It is a man-made disaster, fueled by the lucrative military-industrial business made up of large-scale arms deals such as those signed in Riyadh last week.

Yemen’s so-called “forgotten war” is actually the proxy war that just keeps giving, creating jobs for the Americans, the Saudis, and the British, one Yemeni child at a time.

At a United Nations meeting in Brussels last month, donors pledged $1.1 billion in aid for Yemen—half the amount that the United Nations considers necessary to avert a famine. While such aid is important, given that Yemen is now the world’s largest humanitarian crisis since 1945 in which seven million people do not know where their next meal will come from, it is ultimately a Band-Aid solution.

A political settlement that requires an end to the violence is crucial if Yemen is to get back on its feet. A halt to the arms sales by both the U.K. and United States is a critical first step. Lifting the blockade of ports such as Hodeida to allow humanitarian aid in is another step that must be implemented urgently. A serious revival of the peace negotiations where all parties to the conflict could participate is another obvious priority.

Given the resilience of the Houthis and their allies, as well as their superior familiarity with the landscape where battlegrounds could emerge, continued air bombardments are highly unlikely to be successful. Bombing the Houthis into submission also means further displacement, increased food insecurity, and thousands more dead. The last two years have shown the tragic human cost of such a ruthless air campaign. It is time to divert the billions of dollars spent on this thus far failed war toward solutions that prioritize humanitarian aid and political negotiations to end the violence. However, external powers such as the U.K., the United States, and Saudi Arabia must also seriously pursue negotiations if they are to have any chance at success. The war in Yemen has not made the region any more secure. Feeding more weapons to the war will further destabilize Yemen and the region.

The culprits in the war in Yemen are many, as are the drivers of the conflict. Resource distribution, tribal rivalries, so-called counterterrorism initiatives, and a geo-political wrangling over Iranian versus Saudi dominance have all claimed the lives of innocent civilians. Many of these deaths, along with the cholera outbreak and widespread starvation, are preventable. The entirely unethical multi-billion dollar arms deals, however, continue to be signed without so much of a mention of those directly affected by their deadly consequences.

Fahad Al-Dahimi provided research assistance for this post.

Commentary

Reaping the fruits of war in Yemen

May 30, 2017