Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

A colleague once noted that when people ask him what Iran might do under any given circumstance, he usually has one of two answers to offer: “I don’t know” or “It depends.” When it comes to India’s relationship with Iran, perhaps the best answer to most questions is “it’s complicated.” This is not, however, usually the way the relationship is portrayed. Indian policymakers publicly tend to emphasize the historical and civilizational ties that India and Iran share. In the U.S., especially outside the executive branch, it is India’s oil imports from Iran and high-level India-Iran visits that get (mostly negative) attention. This week, one of those visits is taking place, with Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif traveling to India, seeking to “open a new chapter” in the relationship. While viewing his trip, it’s worth keeping in mind the complexity of the relationship and the fact that there are not just elements driving India’s ties with Iran, but some that limit it as well.

There are certain factors that have driven India’s desire to maintain a relationship with Iran and that are likely to persist. The role of the first factor often mentioned—historical and civilizational ties—is often overstated. They do provide a link, but these ties neither prevented a frosty India-Iran relationship through most of the Cold War nor led to a close one after the 1979 revolution.

India’s Energy Needs

India’s energy needs are a crucial element. The country today is the fourth largest consumer of energy in the world, soon likely to become the third. Oil constitutes nearly one-fourth of Indian energy consumption. Over three-quarters of that oil comes from abroad—a share that is only expected to increase. India has significantly reduced its oil imports from Iran, mostly as a result of sanctions, but also because of the availability of other import sources and India’s preference for diversifying its dependence as much as possible. However, Iran still accounts for 6% of total Indian oil imports.

India is also increasingly looking abroad for natural gas. It does not import any from Iran, but there have been (unsuccessful) discussions in the past about a long-term supply contract, as well as an Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline. These kinds of deals could be back on the agenda, depending on how various bilateral, regional and global factors—including the nuclear negotiations—play out. Additionally on the energy front, Indian companies, especially state-owned ones, continue to have investments or interest in investing in the Iranian energy sector. Till recently, Iran also was a major export destination for Indian refiners.

The potential development of non-energy bilateral economic ties is another factor. Ironically, sanctions might have given additional impetus for the exploration of such interaction. With Indian companies finding themselves having to pay Iran for oil in rupees, which can only be spent in India, there has been a felt need to find things that Iran can buy in India. While sanctions relief has meant that companies can potentially pay Iran a certain amount in dollars, these cannot cover all they owe Iran. Even beyond this, the government and Indian companies would like to explore economic opportunities with and in Iran.

Attractive Corridor to Central Asia

Potential access to Afghanistan and Central Asia through Iran is another crucial reason for India’s ties with Iran. Since Pakistan is not currently a feasible transit option to the region, New Delhi finds the prospect of using an Iranian transit corridor attractive. India’s desire to invest $100 million to upgrade the Iranian port of Chabahar is linked to this need, as well as to China’s investment in the Pakistani port of Gwadar. The impending drawdown, if not withdrawal, of NATO troops from Afghanistan has made this Iran route—as well as potentially broader India-Iran cooperation in and on Afghanistan—even more crucial for the Indian government.

A fourth element in play is domestic. India houses 10-15% of the world’s Shia population, much of which is concentrated in electorally-significant areas. This community and the even larger Sunni one also make the Indian government sensitive to any Sunni-Shia tension in the Middle East that could potentially spillover into India.

These factors don’t just constitute the backdrop for Zarif’s visit, they will be items on the agenda as well. They are also the reasons that New Delhi would like to cooperate with Tehran and to see a normalization of Iran’s relations with and standing in the international community. However, even if the latter occurs, there are also factors in play that will serve to limit the relationship from India’s perspective.

Regional Complications

First, India’s energy relationship with Iran hasn’t been without strain. New Delhi has had doubts about Tehran’s reliability and stability as a supplier. Iran is thought to have reneged on some deals, tried to renegotiate others, and given China and its companies better terms in the Iranian energy sector. While an Iran under the pressure of sanctions has shown slightly more inclination to offer India and its companies better terms, Indian officials note that the Iranians remain tough negotiators in this arena. Tehran has also not been above using India’s oil and gas needs to pressure the Indian government in the foreign policy realm. This was perhaps most evident when Iranian officials seemed to link energy deals to India’s votes at the IAEA. This did nothing to increase New Delhi’s confidence in Iran and reinforced its general tendency to diversify its dependence partly in order to limit any one country’s leverage on it.

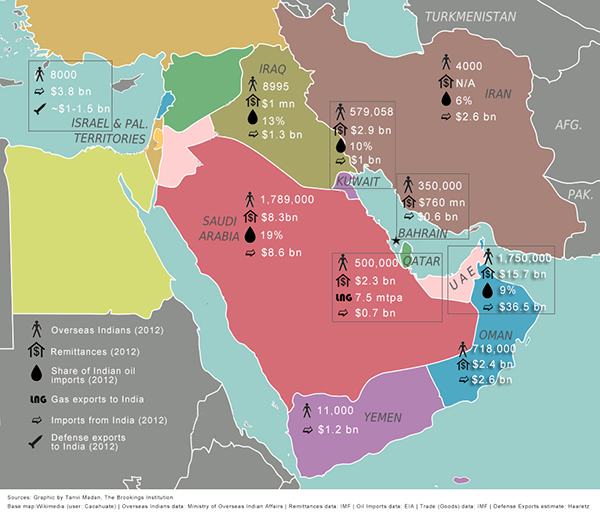

Second, even as India has ties with Iran, it also has a number of other key relationships in the region that will keep it from getting too close to Iran. Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Cooperation Council states supply a significant amount of the oil India imports. Qatar is also its largest source of imported natural gas. The large Indian diaspora in these countries, which is a major source of remittances, and the significant Sunni population in India (over 120 million) also make these relationships crucial. In addition, there are existing and potential trade and investment ties at stake with these countries. For Delhi, a relationship with Riyadh is also particularly critical because of the leverage the Saudi government is thought to have with Islamabad.

There is an overall sense in India that these countries are taking it more seriously—partly thanks to Iran, partly in the Saudi case because of American urging, but also because of India’s potential as a market as other consumers drop off the list. These countries’ interest in India has been evident in the fact that in the ten days before Zarif’s trip, Delhi saw visits from the king of King of Bahrain, the Saudi crown prince, the Omani foreign minister and the chairman of the Kuwaiti national security apparatus.

India’s Relationship with the United States and Israel

Beyond these Arab states in the Middle East, India’s relationship with Israel has also become crucial. That country has become one of India’s largest defense defense suppliers, and is also seen as a major source of agricultural technology and tourism revenue. Furthermore, Indian companies are keen to invest in Israel’s technology sector. The two countries are also negotiating a free trade agreement. Since the Mumbai attacks, shared concerns about terrorism have created additional space for bilateral cooperation.

Finally, India’s relationship with the United States, and American (especially Congressional) concerns about Iran have also affected the India-Iran relationship. Indian officials resent pressure from the U.S. on India-Iran ties to Iran—they especially find public pressure to be counterproductive, but they realize that these links with Iran do create complications in the critical India-U.S. relationship. India has not been above using U.S. concerns about Iran as well—for example, with officials advocating for U.S. natural gas exports to India suggesting that it’d help ease India’s energy dependence on countries like Iran.

Keeping Each Other at Arms Length

There have been additional causes for strain in the India-Iran relationship—some that have played out quite publicly, thus shaping the Indian public’s view of Iran. In 2012, a terrorist attack on an Israeli connected with the embassy in Delhi raised hackles. The Indian foreign ministry played down the Iran connection publicly. The Indian home ministry and law enforcement authorities, however, implicitly or explicitly linked the attack to Iran and complained about the lack of cooperation from Iran in investigating it. Beyond concern about such acts of terror per se and about the impact on India-Israel relations, if there is another such attack, it puts the Indian government in a tight spot—finding itself calling on other countries to criticize Pakistan for allegedly supporting terrorism on Indian soil, while staying silent on Iran. More recently, Iran found itself in India’s bad books as a result of its nearly-month-long detention of an Indian ship transporting crude oil from Iraq to India. Finally, over the last few years, there has been a negative reaction whenever Iranian officials and commentators criticized India for its relations with third countries. A glimpse of this was evident in the reaction to an Iranian’s Iranian’s comments to Indian counterparts during a Track-II dialogue that included the critical assertion “your qibla is Washington.”

Even as Zarif’s visit is an opportunity for India to get an update on Iran’s perspective on the P5+1 negotiations and explore avenues of greater cooperation (especially if those negotiations succeed), the persistence of these concerns will likely limit the extent of that cooperation. Barring a bilateral shock, India will continue to seek to establish a relationship with Iran that’s not too close, not too far, but just right. This is likely to be the case regardless of who takes office in India after the national elections that’ll be held over April and May—though a third front (i.e. non-Congress party-led or non-BJP-led) coalition government might place somewhat different emphasis especially rhetorically.

Commentary

India’s Relationship with Iran: It’s Complicated

February 28, 2014