As expected, July’s employment numbers suggest that the road to recovery will be long. The economy as a whole lost 131,000 jobs as layoffs of temporary Census workers continued. Private sector employment increased by 71,000 jobs, building on June’s increase of 31,000 jobs. So far this year, the economy has added 654,000 jobs, with 630,000 coming from the private sector.

In past blog posts, The Hamilton Project has explored the “job gap,” which measures the number of jobs the economy needs to create to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the 125,000 people who typically enter the labor force each month. This month, we also explore how employment levels resulting from the Great Recession compare with the employment impacts of previous recessions.

How Do Employment Levels Compare?

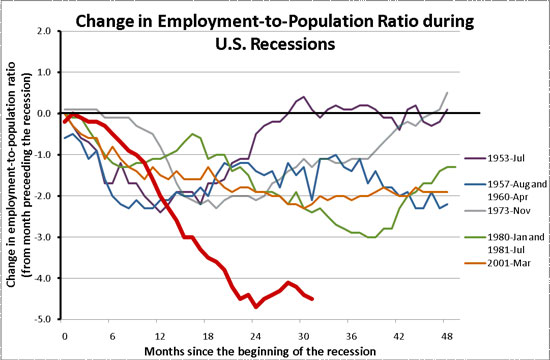

To get a sense of how long the current recovery may take, we compared this recession to past recessions. The ratio of the number of people employed to the total working-age population, often called the employment-to-population ratio, is the broadest measure of employment. This ratio captures both employed and unemployed workers as well as discouraged workers who leave the labor force. Consequently, it is a more comprehensive measure of the health of the labor market than the unemployment rate alone.

The graph below plots the change in the employment-to-population ratio from the beginning of each recession for the six U.S. recessions with the largest declines in the employment-to population-ratio since 1948–the first year with data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (The 1957 and 1960 recessions and the 1980 and 1981 recessions are combined because of their close proximity.) A lower employment-to-population ratio means that more members of the working age population are unemployed or have taken themselves out of the labor force.

We can see that the drop in the employment-to-population ratio for this recession is already far more severe than the drop for any other recession in the past 50 years. At the lowest point, the employment-to-population ratio declined 4.7 percent during the Great Recession (in December 2009), more than fifty percent larger than the second biggest recorded decline during the combined 1980 and 1981 recessions in which the fraction of Americans employed fell 3.0 percent.

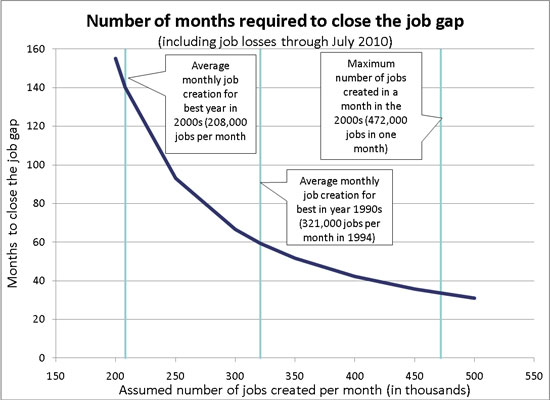

Just as troubling as the depth of the decline in employment is the duration of the decline—more than 24 months. In many earlier recessions, employment resumed steady growth within two years of the start of the recession. We saw exceptions to this when the economy experienced a double dip and fell quickly into another recession—as in the 1957 or 1980 recessions. Another notable exception is the recession that started in 2001, which was not followed by a strong rebound in employment. Indeed, the 73-month period from the end of the 2001 recession to the beginning of the current recession was the weakest rebound in payroll employment growth after any recession since at least 1948. As the updated jobs gap graph shows below, these factors imply that restoring employment to pre-recession levels will require far stronger job gains than we experienced during the last recovery.

The Job Gap

After today’s employment numbers, the job gap stands at 11.6—an increase from last month’s 11.3 million job gap.

The U.S. economy will need more robust growth to close this gap. If future job creation reaches about 208,000 jobs per month, the average monthly job creation for the best year for job creation in the 2000s, it will take almost 140 months (about 11.5 years) to reach pre-recession employment levels. In a more optimistic scenario with 321,000 jobs created per month, the average monthly job creation for the best year in the 1990s, it will take 59 months (almost 5 years). The chart below shows the amount of time necessary to close the job gap for different rates of job creation.

The employment situation continues to be an issue of key concern to policymakers and the American people alike. How the burden of unemployment has been distributed throughout the workforce is also emerging as an issue of focus. In the coming months, The Hamilton Project will explore the uneven impacts that the Great Recession has had on different types of workers and their communities. As part of this work, we will release several proposals focused on ways to aid “distressed communities” during an October 13 policy forum in Washington, DC. These proposals are intended to target some of the hardest hit communities and provide a range of options for helping their residents get back to work.

Commentary

The Long Road Back to Full Employment: How the Great Recession Compares to Previous U.S. Recessions

August 6, 2010