The United States spends more on health care than any other developed country and outcomes are middling. Chronic diseases account for nearly half, 47 percent, of the expenditures. Use of non-traditional health services, such as home visits by a nurse, and enhanced community resources can improve quality and possibly reduce costs. This type of care is focused on keeping people well, not treating them once they get sick. These person-centered services are often best delivered outside of conventional medical care. Recent work on asthma care by the Center for Health Policy and the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA), including an expert roundtable, webinar, and white paper, highlights this issue.

Asthma is a highly prevalent chronic condition that accounts for a large portion of medical expenditures, but effective control for high-risk patients often requires intensive education and home-environmental assessment of indoor air issues. Asthma triggers like mold, dust, smoke, and chemicals are often associated with substandard housing, and as a result, asthma prevalence is highest in racial minorities and low-income households. Although local departments of health, housing authorities, and other community providers can improve asthma care, they are often not well coordinated with clinical services. As the health system transitions to population-oriented health (which can be thought of as the health outcomes of a group of individuals, and the distribution of these outcomes within the group) practices will need to more effectively engage community providers to improve disease management.

What needs to change in the traditional health model?

Care transformation will lead to broader and more patient-centered conception of patient care, but only if three factors are addressed at the practice level (Figure 1).

- First, clinicians need to adopt a team-based approach to care, which allows all providers to practice at the “top of their license”, where each member of the care team contributes to the patient’s care to highest level of their education and training. This approach frees up the physicians’ time to establish care plans and focus on the sickest patients, while delegating less complex tasks to other members of the care team. For example, nurses can teach proper nebulizer technique and develop asthma action plans, and social workers can connect patients with community resources at housing authorities and public health departments.

- Second, engagement with community, social, and public health providers is essential to improving patient outcomes. In the case of asthma, a broad array of national and local partners can help to prevent exposure to asthma triggers and improve patient adherence with their physician’s instructions. These providers have specialized skills outside of the traditional scope of a medical practice. For example, medical care may be more effective when local health departments and community health workers visit homes to perform air quality checks and offer environmental remediation.

- Third, new payment models are needed, which offer health professionals more autonomy and shift the emphasis from paying for volume to paying for value. These models need to reward physicians for engaging with community providers and hold the system accountable for a person’s total health. Alternative payment models can provide clinicians with the resources and flexibility to engage services in the community that address the underlying causes of poor asthma control.

A number of alternative payment models (APMs) have emerged that can support community providers in delivering optimal asthma care. Expanded fee-for-service could be used as an interim model to support community health workers, social workers, or clinical support staff in connecting patients to community resources. Global budgets and capitation, where one payment is paid to the provider for a population of patients over a defined period, can enhance coordination and collaboration by aggregating payments and accountability across providers. Community asthma programs may even incentivize cost savings by financing the upfront investments through social impact bonds, where investors are promised a portion of the savings from avoided hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Practical next steps on how to transform the system

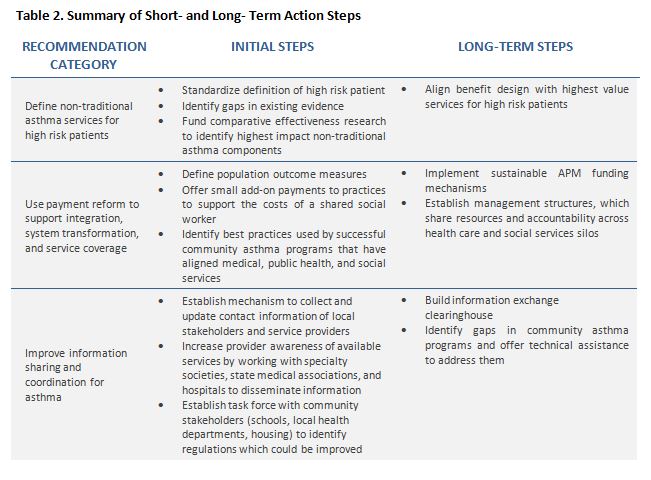

Both practices and systems will proceed through multiple transitional steps to achieve more population-oriented health practice. Improved communication and coordination between the health care, social service, and public health sectors are important opportunities. A shift toward a public health focus, development of meaningful and valid metrics, and APMs that facilitate shared accountability for population outcomes are all important. Below we present a set of actionable recommendations that clinicians, hospitals, payers, and governments can implement in the path toward system transformation.

Commentary

Improving chronic asthma management through population health

September 14, 2015