It is well recognized across the health care industry that the major goals of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) include not only expanding health insurance coverage, but also improving the quality of care and the patient health care experience. A key strategy in achieving these goals is improving the efficiency and delivery of care through innovative financing mechanisms and new delivery models, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), bundled payments for acute and post-acute care, and population-based models that aim to improve the health of entire communities. These alternative models emphasize quality and outcomes, while moving care away from the traditional and predominant method of fee-for-service (FFS).1

The Frontline Work Force

Many conversations focused on the implementation of these models typically emphasize the role of physicians. However, the success of these models relies heavily on the support and manpower of a multidisciplinary team; particularly “frontline health care workers.” Frontline workers may include medical assistants (MAs), medical office assistants, pharmacy aides, and health care support workers. Oftentimes, they provide routine, critical care that does not require post-baccalaureate training.2

For example, MAs can play an important role in a medical home model. Upon discharge from the hospital, frontline workers can provide direct outreach to patients that are at high risk for readmission, and discuss any lingering symptoms, worsening of conditions, or medication issues. If necessary, MAs can assign a high-risk patient to a social worker, care coordinator or nurse.3

In a team care environment, frontline health care workers are essential for taking over routine tasks and allowing physicians to employ their specialized skills on their most complex patient cases, which allows all team members to work at “the top of their license”.4 Frontline workers can also bridge the gap between patients and a multitude of providers and specialists; help deliver care that is culturally and linguistically appropriate; and provide critical patient education and outreach outside of regular office visits.

A Workforce in Need of Reform

While team-based care is widely accepted as an industry norm, its current infrastructure is not well-supported. While the frontline workforce represents nearly half of all health care professionals, they are markedly underpaid, underappreciated, and lack formal training to transition into higher-skilled and/or higher paid positions.

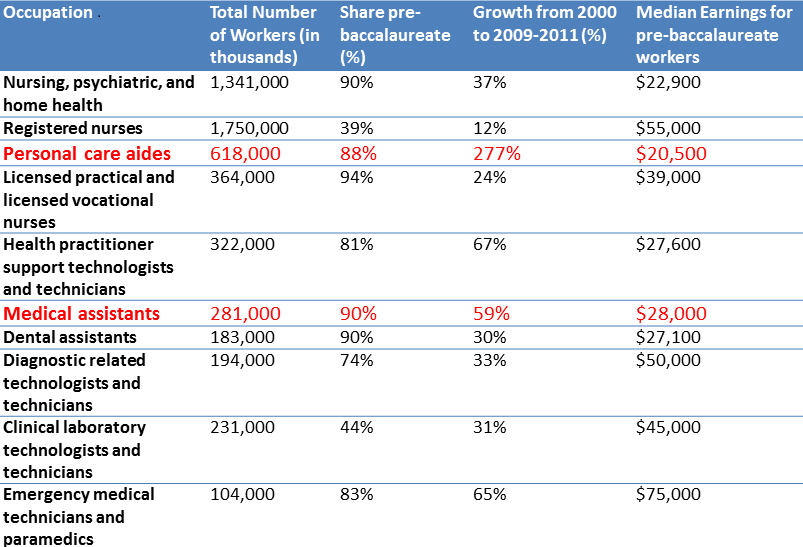

A recent study by the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program “Part of the Solution: Pre-Baccalaureate Healthcare Workers in a Time of Health System Change” demonstrates this glaring disparity between current frontline workforce investment and its value to health reform efforts. The study analyzes the characteristics of the top ten ‘pre-baccalaureate health care workers’ (staff that holds less than an associate’s degree) within the US’s one-hundred largest metropolitan areas (see Table 1).

Table 1: Top ten pre-baccalaureate health care workers in the US’s top one-hundred metropolitan areas

Personal care aides represent a striking example of the underinvestment in frontline workers. The study shows that personal care aides have the lowest levels of educational attainment compared to their peers (32% have no more than a high school diploma), and have the lowest median earnings ($20,000 annually). Meanwhile, The Center for Health Workforce Studies’ (CHWS) estimates that this profession is among the top three national occupations with the highest projected job growth between 2010 and 2020. They are also in highest demand: between 2010 and 2020 there will be an estimated 600,000 personal aide vacancies.5 According to this study, MAs are also among the least educated and lowest paid frontline professions. Ninety percent lack a bachelor’s degree and a significant share (29%) are classified as ‘working poor.’

Policy Solutions

A number of policy solutions can be applied to enhance the frontline worker infrastructure. Our recommendations include:

Invest in front line health care workforce training and education. Case studies from a recent Engelberg Center toolkit, outlines how providers are training their frontline workforce to master fundamental skills including care management, patient engagement, teamwork, and technological savviness.

For example, a New Jersey ACO carried out clinical transformation by investing in new frontline staff, and by redefining the role of medical assistants to include health coaching. The return on investment for employers is potentially large. After injecting a substantial initial investment into this project, this ACO saw a 12.3% decrease in net health care costs within the first year of the program’s implementation; as well as significantly improved efficiency, quality of care and patient experience. As the educational curricula for frontline professions are largely variable, more attention should also be spent on the quality of educational content to train these occupations, as well as on developing an understanding of how delivery systems are augmenting traditional educational curricula.

2. Active inclusion of frontline health care workers in payment reform. Although the services of frontline health care workers are beginning to play a role in new payment models, typically frontline staff does not benefit directly from any bonus payments or shared savings incentives. However, their increasingly valuable role in the care team may warrant allowing frontline health care staff to be included in the receipt of shared savings and/or bonus payments based on the achievement of specifically tailored performance and outcomes targets.

The increasing demand for frontline health care workers, driven in part by the ACA’s payment and delivery reforms, will likely spell out a brighter future for these occupations, whose services had routinely been undervalued and underpaid. Future policy efforts should be focused on extending educational grants that have been aimed at primary care and nursing to frontline workers, as well as considering dedicating portions of shared savings to enhancing the earning potential for frontline workers. Some efforts, such as the U.S. Department of Labor’s recent rule to grant wage and overtime protections to home health and personal care aides, are early suggestions of a shift toward greater respect and empowerment for these occupations. It is yet to be seen what effects the continuation of such efforts will have on their high projected attrition trends.

1 United States Senate Committee on Finance. Testimony of Kavita K. Patel.

2 Hunter J. Recognizing America’s Frontline Healthcare Worker Champions. National Fund for Workforce Solutions Blog. November 2013.

3 Patel K., Nadel J., West M. Redesigning the Care Team: The Critical Role of Frontline Workers and Models for Success. The Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform, March 2014.

4 Patel K., Nadel J., West M. Redesigning the Care Team: The Critical Role of Frontline Workers and Models for Success. The Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform. March, 2014.

5 The Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS). Health Care Employment Projections: An Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Projections 2010-2020. March, 2012.

Commentary

What payment reform means for the frontline health care workforce

August 5, 2014