This piece highlights key findings from the new report “Global development disrupted: Findings from a survey of 93 leaders,” which can be downloaded here. A launch event will be held at Brookings on April 8. Note: After going to press, the authors realized that the name of an additional respondent was omitted, making the total number of leaders surveyed 94, not 93.

Last year, we interviewed 93 leaders from government, NGOs, private development contractors, corporations, foundations, and multilateral organizations on how they see global development changing, what they forecast in the near and mid-term future, and how their own organizations are adapting. Their perspectives coalesce around a few broadly held themes—and diverge widely on a host of other topics. Overall, we found a fragmented field that is very much in transition. Development organizations are struggling with uncertainty and striving to keep pace with rapid change. Leaders are proud of what they do and the advancements in global development but painfully aware of the lack of progress in many areas and of the development sector’s shortcomings. Changes in the sector elicit both excitement and fear. For leaders, they induce worry about the relevance of their own organizations and the ability of the sector to adapt and add value.

Though we encourage readers to review the full report to appreciate the breadth and richness of the findings, we summarize three top conclusions below:

1. Funding in Flux

The most-mentioned issue is the future of funding for development. There is broad concern over a plateau in official development assistance (ODA), and inadequate financing for development overall as well as for specific areas of need. There is also concern for the long-term financial health of development organizations that are overly dependent on government donors. At the same time, development leaders are excited but uncertain over the prospects of alternative sources of finance. They are encouraged by the potential of domestic resources mobilization—resources generated through tax revenues and private finance within partner countries—and the ability of rapidly growing low- and middle-income countries to take control of their own development. Private finance is seen as offering a sizable new source of funding and there are exciting new efforts by governments to leverage private capital—like the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation created by the BUILD Act. Respondents note that private finance is not available for the poorest countries and doesn’t address certain public goods, but they see new development finance mechanisms as potentially tapping into trillions of dollars. There are also promising new developments related to impact investing, social enterprise, and fee-for-service, but development organizations cannot yet count on these mechanisms as dependable revenue streams sufficient to the scale of the challenges they seek to address.

2. Players Proliferating

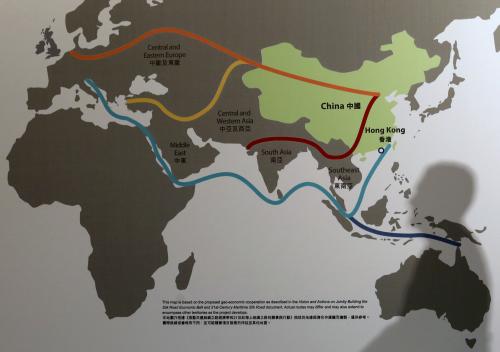

Survey respondents note the proliferation of new actors in the development field—China, India, and other large middle-income countries; foundations and philanthropists; corporations and social investors. This expansion of players is generally seen as positive because they bring more resources, expertise, and alternative approaches to development challenges. But it also raises concerns over new players that bring different norms, expectations, and incentives—particularly China—and the potential for negative outcomes.

3. Shifting Landscape

The whole development landscape is changing rapidly, in ways far beyond the already noted shifts in funding and actors. For development leaders, this adds even more complexity to their missions.

Two-track world

As middle classes grow and more countries enter middle-income status, respondents note stagnation and even backsliding in fragile countries. This is producing an increasing gap between countries that are developing and growing wealthier on the one hand and those mired in poverty and instability on the other. This two-track world leaves the development community with a question of how to add value in the first group of countries and frustration as to what interventions will move the needle in the latter. It produces an uncertainty as to what models development organizations should prioritize going forward and how development organizations ought to position themselves to achieve the greatest impact.

Movement of people

The historic level of refugees and displaced persons in the world—approaching 70 million—is a major challenge for organizations seeking to serve those forced to leave their homes and communities. Since many of these people are dislocated for years or even permanently, old models of humanitarian relief are insufficient and the development community must find more sustainable approaches that go beyond meeting short-term basic needs. In addition to addressing the needs of refugees and displaced persons, there are concerns about a backlash in response to accepting refugees, and frustrations over how to stem this man-made catastrophe.

Localization

Development leaders point to localization as a major positive trend. Increasingly local actors possess the knowledge, talent, and institutions to address local challenges and are best positioned to address them. Foreign donors and implementers can best play a supporting actor role. This leads some leaders to wonder what the future is for international development implementers and where they can best add value, but still welcome the trend.

Demography

Demographics are changing development, even beyond the explosion of migration. Many regions are experiencing an unprecedented youth boom, coupled often with increases in urbanization. While some worry about how to educate and provide employment for the growing youth cohort—and their potential for radicalization if those solutions are not found—more generally, youth in developing countries are viewed positively. Booming youth populations offer the opportunity of more and better-trained workers, changing cultural norms on democracy and women, and new and creative ideas that can fuel growth and positive change. There is also growing attention to the need for societies to educate and empower women and girls, allowing them to play a larger and more constructive role in family, community, work, and political life.

Technology

When we asked leaders what is new and innovative in their organizations and the field, technology topped the list. However, when asked what specific types of technology respondents are excited about, there was no consensus. Indeed, well over 30 different technologies were mentioned. Some see technology as a driver of positive, real change, providing development organizations with better tools to communicate with disparate communities and quicker data-driven interventions. But leaders do not view technology as an unadulterated good. Technology can create jobs but also threatens to displace millions of workers. There is particular concern over autocratic leaders using technology to enforce their rule. There also is great frustration at the inability of development actors to adapt technology and keep up with its rapid change. Along with excitement over technology is the better access to data it brings. Respondents are enthused over the greater use of data and data analytics. They see the power of data in analyzing problems, driving solutions, and empowering people to hold those with authority accountable. The frustration is that development organizations have yet to figure out how to organize and effectively use data, and that funders are not willing to provide investment in the capacity to collect and analyze data.

Commentary

How global development leaders think their field is changing

March 26, 2019