Despite a crisis of confidence at the national level, a significant majority of Americans still believe in the ability of their local governments to deliver. This is good news, because U.S. cities are increasingly responsible for taking on local challenges with global implications, such as pollution, violence, climate change, and economic opportunity and security.

Local actions, global lessons

As municipalities go about their business, they are increasingly turning to their peers, engaging in city-to-city networks and communities of practice (an estimated 300+ globally) to share best practices, experiment with innovations, and design new solutions. It reflects a problem-solving mentality that has earned many U.S. city leaders a reputation for pragmatism over politics.

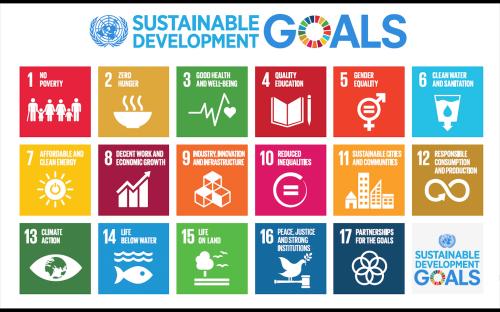

This is the way American cities such as Los Angeles, New York City, and Pittsburgh come to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs, collectively agreed by the world’s nations in 2015, reflect national commitments to end poverty, achieve economic prosperity, and reduce inequality and injustice while promoting environmental sustainability and tackling climate change.

Yet cities worldwide and in the U.S. are taking on the SDGs themselves, viewing the goals as a planning tool for prioritizing, measuring, and mobilizing social, economic, and environmental progress. On November 29 at Brookings, leaders and experts from these three cities will explore the local value proposition of the SDGs to U.S. cities along several dimensions:

Common Language: As the SDGs have grown into the lingua franca of development globally, they give city officials, stakeholders, and even residents a common and immediate frame of reference when engaging counterparts. The globally accepted and vetted framework offers the potential for comparability, allowing cities to measure themselves against other communities using a holistic vision of sustainable development.

Clear Diagnosis: The SDGs help to view at once the multiple dimensions of development that administrators often pursue through separate offices and stand-alone initiatives. This offers the opportunity to integrate plans to improve—among other things—infrastructure, equity and inclusion, economic growth and jobs, resilience, and the environment. It can also help identify gaps and interdependencies that would otherwise go unnoticed or unexploited. New York City, which developed its OneNYC city strategy before the SDGs were adopted, recognized the overlap and mapped its local milestones to the global goals. This year it became the first city in the world to submit a review of its progress to the United Nations. This advance in accountability allowed city leadership to report on the city’s progress using a recognizable framework accessible to residents and other stakeholders.

Concrete Objectives: As a set of timebound, outcome-based targets, the SDGs give meaning to metrics. It is rare for elected city leaders and their communities to commit to the level of specificity contained in SDG targets. For example, while many communities might endorse a commitment to reducing poverty, it can be much more powerful—and motivating—to commit to reducing poverty by 50 percent by 2030 (SDG target 1.2). The ambition of the goals translates into a universal imperative to “leave no one behind,” forcing municipalities to focus on its most vulnerable residents. While the perception lingers that the SDGs have limited relevance for high-income countries, just the simple combination of target 1.2 with target 10.1, which commits to achieving and sustaining income growth of the bottom 40 percent at a rate higher than the national average, demonstrates that the agenda directly addresses the economic dynamics buffeting many communities in the U.S.

Concerted Action: This type of data-driven goal-setting is embodied in the commitment made in 2017 by Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti to decrease the number of unsheltered Angelenos by 50 percent in five years, and functionally end homelessness in 10 years. This predates the city’s commitment to the SDGs, but it demonstrates the mobilizing effect of aligning policy and budget against a publicly accountable goal: a county bond issued for $355 million annually for services and programs, a city bond issued for $1.2 billion for supportive housing, and a mayoral executive directive given to expedite the process of standing up temporary shelters. At the global level, the SDGs have been catalysts for new partnerships among government and the private sector, universities, civil society, and citizens. Investment managers such as PIMCO and Calpers are analyzing how the SDGs measure environmental, social, and governance factors critical to financial performance, while businesses are seeking ways to highlight their leadership.

Another way for America to lead

As cities cooperate through networks such as C40 to address climate change, 100 Resilient Cities to deal with shocks and stresses, and Strong Cities to end violent extremism, they have increasingly found a collective voice on tough global issues, separate from their national government. While the full implications of this political shift are unclear, it has provided an alternative path for American global leadership. One of the most compelling virtues of the SDGs reported by cities globally is their ability to excite and engage citizens, including youth and millennial leaders. This may help cities deal with the trickiest part of their global engagement: getting their residents to care about—or at least see the value of—their forays on the global stage.

Adopting the SDGs is quite easy; serious implementation is much harder. Cities will always need to find customized ways to manage and prioritize. But the SDGs offer a blueprint and useful metrics for city leaders to advance local economic, civic, and environmental imperatives. They give U.S. cities an incentive to play a prominent role in solving the world’s problems while solving their own. At a time when traditional forms of global cooperation are under pressure, this may be a good way for the U.S. to retain the mantle of leadership in development, both at home and globally.

Commentary

Can US cities help the world achieve the Sustainable Development Goals?

November 29, 2018