Today is the International Day for the Eradication of Extreme Poverty. Recent stories about a “new poverty narrative” for the 21st century have captured world headlines. Whether discussing Nigeria, India, or the tipping point of the new global middle class, economists now broadly agree on one central theme: If we want to end poverty, we need to focus on Africa.

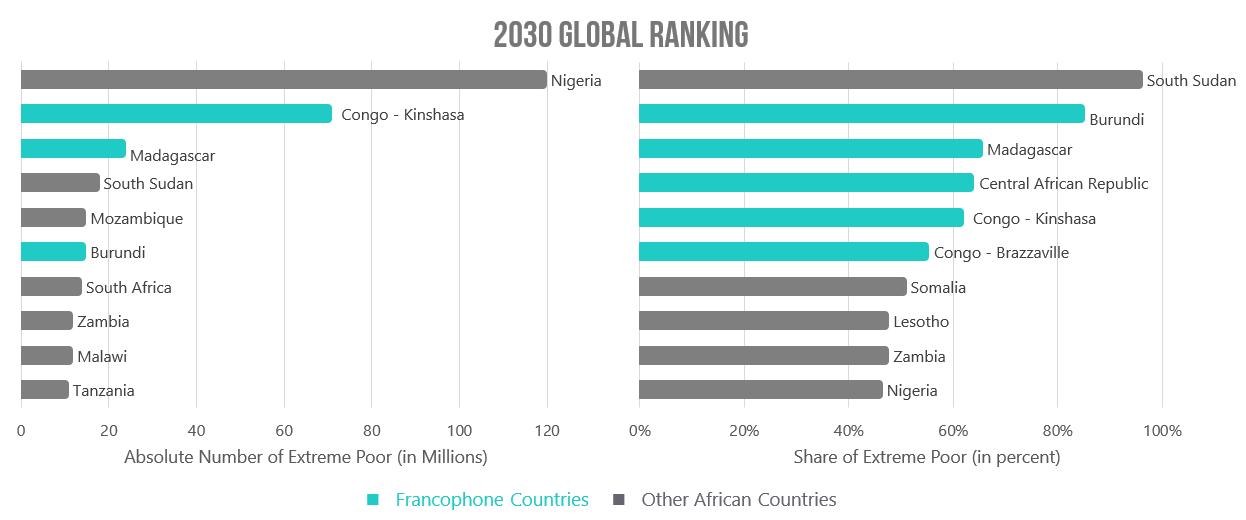

Under current projections, 88 percent of the world’s poorest are expected to live in Africa (some 414 million people) by 2030. Aside from countries like Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, North Korea, and Venezuela, many non-African developing countries can end extreme poverty by 2030. African countries, however, will probably only make modest gains. In fact, if current trends persist, by 2030 the top 10 poorest countries in the world will all be African—both in terms of absolute numbers and share of extreme poor as a percentage of the total population (Figure 1).

Figure 1: African countries will dominate poverty by 2030—Anglophone and Francophone alike

Overall, the number of poor people living in Africa is currently growing by five people per minute. Under current projections, only by 2023, will that number begin to recede. That being said, African countries vary greatly from one another in many ways, including their experience with, and response to, extreme poverty. For example, Ethiopia, the poster child of famine in the 1980s, is now expected to eradicate extreme poverty by 2029. Ghana is expected to follow soon thereafter in the same year. On the other hand, resource-rich OPEC member, Nigeria, is now widely considered to have the highest number of people living in extreme poverty on the planet, and may well see an increase in poverty rates by 2030 as its population continues to grow.

Of course, there are also powerful linkages among African countries, and they could deepen in the coming decade to mobilize local and global support for poverty alleviation projects. For example, the group of 30 African member countries of the Francophonie are largely experiencing the same challenges as the rest of the continent. Out of the 14 African countries currently considered off-track to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SGD) 1, eight are members of the Francophonie. By 2030, one in three people living in extreme poverty—167 million people—will inhabit an African Francophonie member state.

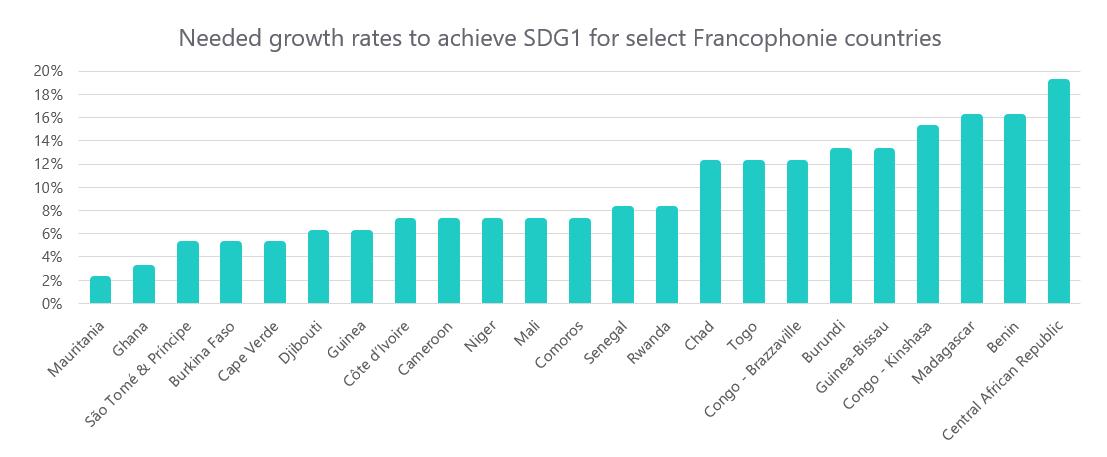

At last week’s Francophonie Summit, the global French-speaking community, led by France, expressed strong support in harnessing African leadership to solve core development challenges such as gender equality and the rights and empowerment of women and children. Such efforts are certainly timely. Current projections suggest that most—but not all—of the African countries of the Francophonie will not have the economic growth needed to achieve SDG1 by 2030 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Growth alone will not be enough to end poverty in Francophone Africa

Needed growth rates to achieve SDG1 for Select Francophonie Countries

Nevertheless, the Francophonie’s overall blueprint for poverty alleviation is similar to the rest of Africa: encourage coalitions of like-minded stakeholders to concentrate their resources on tackling a handful of priorities. In this regard, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s recent Goalkeepers report noted that increasing human capital could make all the difference in changing poverty dynamics in a number of African countries. Of course, even with such targeted support, not every country will be able to eradicate extreme poverty in the coming decade. But for many, it could offer the policy linchpin needed to ensure that many of the 414 million Africans expected to live in extreme poverty will, in reality, have found themselves on much more prosperous trajectories.

Martin Hofer contributed to this blog post.

Commentary

Africa: The last frontier for eradicating extreme poverty

October 17, 2018