Europe is growing old. But the typical factors underlying aging—low birth rates and high life expectancy—do not hold equally everywhere. Longevity in particular is markedly different. Since 1960, life expectancy in Western Europe has risen by around 10 years (from 70 to 80 years). The equivalent figure in Central and Eastern Europe is 7 years (from 67 to 74 years). This difference in life expectancy between the two parts of Europe is greater today than it was in 1960.

The difference in longevity means that Western Europe has a greater share of old people in its population. The British monarch, who sends personal greetings to 100-year-olds, is increasingly busy! On its own, the growing difference in longevity should make Western Europe age more rapidly. Paradoxically, it does not. Median age is set to rise more slowly than in Central and Eastern Europe. By 2020, median age will be lower in Western Europe than in Central and Eastern Europe.

There are three reasons for this. The first is the free movement of people within the European Union. Free movement (which was introduced in stages but is now fully effective everywhere) has allowed many young people to relocate to Western Europe to study or work. Immigration is making Western Europe younger, swelling the ranks of those who earn and pay taxes there, while making Central and Eastern Europe older.

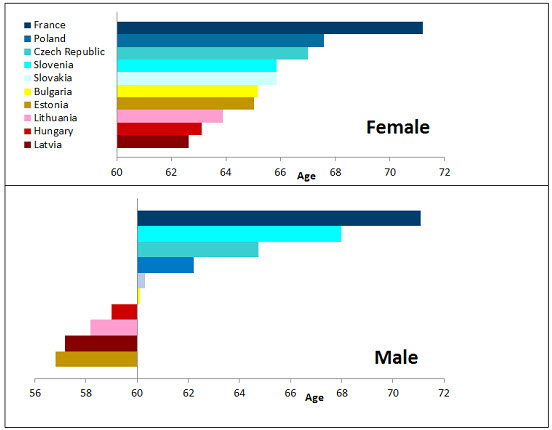

The second reason is the higher level of morbidity and ill-health in Central and Eastern Europe. Morbidity and mortality rates are higher at every age, but the difference is very striking among the middle-aged. Today a 60-year-old in Central or Eastern Europe can expect to live significantly fewer years than his or her Western European compatriots (see Figure 1). For men at 60, mortality risk is higher today than in 1960 in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Hungary, and it is virtually at 1960 levels in Bulgaria and Slovakia. (This is not to be confused with life expectancy at birth, which has risen as previously discussed.)

Figure 1. Men at 60 in Central and Eastern Europe fare worse in 2009 than they did in 1959

How old do you have to be today to have the same mortality risk as a person at 60 in 1959?

Source: World Bank (2015), What’s Next in Aging Europe.

The third reason is lower fertility in Central and Eastern Europe. Many Western European countries, including France, Norway, and the United Kingdom, have seen an upward trend in fertility, and the natural increase of population (births minus deaths) is positive. In contrast, fertility remains stubbornly low in Central and Eastern Europe. Of the nine EU countries where the natural increase in population is negative, seven are in Central and Eastern Europe.

All this means that Central and Eastern Europe is aging more rapidly than Western Europe, even though individuals do not live as long. Does this matter? Yes. Aging of society brings fiscal and growth challenges. The unique features of aging in Central and Eastern Europe mean that the challenges and opportunities are different. Take the case of pensions. Given limited increases in longevity, it will be harder to use increases in the retirement age as a means to control the fiscal costs of state-owned or state-guaranteed pension systems. Countries therefore need to focus more on reducing early retirement which occurs well in advance of the statutory retirement age. Not only would this rein in pension spending, but it would also boost the labor force. The unique demography also provides opportunities. The smaller share of the old (especially those above 80) means countries can plan for the expansion of long-term care before it is needed. Countries can also take advantage of the reductions in fertility and youth cohort size to improve the quality and inclusiveness of education.

The most important implication is for health policy. Much of the greater morbidity and mortality among the middle-aged is driven by preventable conditions such as cardiovascular disease. This is because the health systems, geared to treating in hospital, are not configured to the management of public health with its emphasis on lifestyle changes, prevention, and disease management. Reducing morbidity and mortality would allow the countries to reap a second “demographic dividend” from a healthier and longer-living population.

Milan Kundera, the Czech author, once observed: “Inexperience is a quality of the human condition. We are born one time only; we can never start a new life equipped with the experience we have gained from a previous one…and even when we enter old age, we do not know what it is we are heading for…”

Fortunately, countries are different from individuals. Central and Eastern Europe can learn from the experience of the West and provide for healthier and longer lives for its people.

Commentary

In Europe, life gets shorter for some

April 21, 2015