Turkey is a winner of globalization and economic integration. Opening up to trade and capital flows provided both the engine and the lubricant for Turkey’s economic modernization. In particular, the customs union with the EU, followed by the opening of EU accession negotiations, ensured that Turkey became part of the “European convergence machine.” Just as it has been the driver of progress in the past, economic integration is also central to Turkey’s future prospects. This was the topic of a session at Brookings on Turkey’s trans-Atlantic integration and its prospects to escape the “middle-income trap.” In a previous blog I wrote about that middle-income trap, now let me address the former topic.

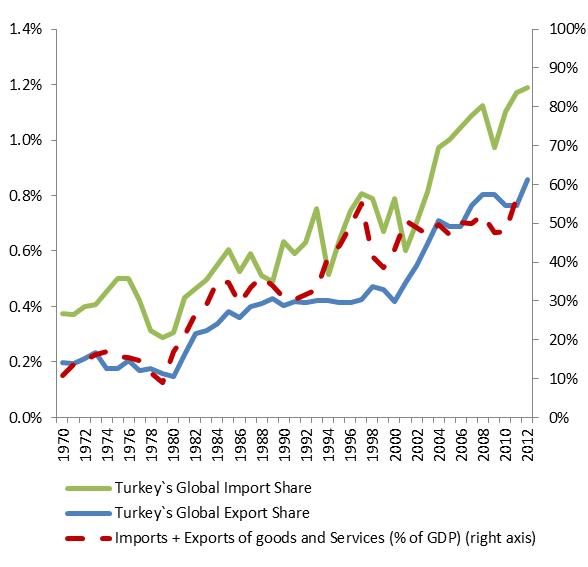

Since the early 1980s, Turkey’s share of global exports and imports has increased fourfold and the share of trade to GDP has risen from barely 10 percent to over 50 percent today (see Figure 1). Turkey’s increasing global economic heft is comparable to developments in other large emerging market economies such as Brazil, India, and Russia, although it does not quite match the performance of China or Eastern Europe.

Figure 1: Turkey’s share of global trade has increased fourfold since 1980

Source: World Bank staff calculations based on World Development Indicators.

Several key policies have contributed to Turkey’s successful integration.

- First, in January 1980, Turkey introduced comprehensive economic liberalization, around one decade before the start of transition in the former Communist bloc. After an initial surge in trade activity, the 1990s were characterized by inconsistent macroeconomic management, culminating in the 2001 financial crisis. Since then, however, liberal economic policies and sound macroeconomic management have allowed Turkey to resume the process of economic convergence and benefit from abundant global liquidity.

- Second, Turkey’s customs union agreement with the EU, in effect since January 1996, has been a catalyst for the technological modernization of Turkey’s manufacturing by forcing the adoption of European quality standards and encouraging the integration into European production networks. Intra-industry trade—one summary measure of the extent of trade within integrated value chains—rose from 30 percent to 50 percent of Turkey-EU trade between 1990 and 2012. Moreover, the World Bank estimates that because it avoided the need for costly rules of origin, the customs union agreement boosted Turkey’s exports to the EU by up to 7 percent relative to a free trade agreement.

- Third, Turkey’s investments in infrastructure have kept up with the needs of a growing economy. Thanks to substantial public and private investments in roads, airports, seaports, and customs facilities, for instance, Turkey’s logistics performance is on par with many high-income countries; Turkey is ranked 31st in the world, ahead of competitors such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Mexico, Romania, or Brazil. Good logistics are essential for an effective participation in global value chains, which is where much of the recent growth in trade has taken place.

Yet in the last three years, Turkey’s economic engine has started to sputter. Some believe that the reason is over-reliance on a weak EU economy, and that group thus favors a diversification by Turkey to other markets. Indeed, as EU markets have slumped, Turkey’s trade with the Middle East has increased and Turkey is successfully expanding to markets in Africa and Latin America. However, it would be wrong to deduce from this that further integration with the EU is unnecessary. Our analysis shows that it is precisely the firms that have successfully established themselves in the EU market that are best at diversifying to third markets. The same firms also have higher productivity growth and pay higher wages than firms without exports to the EU. The European market may not be the most dynamic in the world, but it is still a standard setter for quality that cannot be ignored.

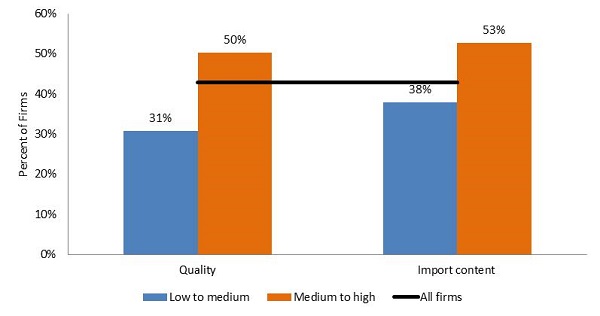

Figure 2: The chances of an exporter surviving increase with higher quality and greater import dependence

Source: World Bank calculations based on Turkstat industrial census. Note: The chart shows the probability of a firm surviving after 5 years in an export market. The blue bars show, respectively, firms with product quality and import content below the sample average. The orange bars show firms with above average product quality and import content.

Others argue that Turkey needs to reduce its reliance on imports to close a chronic trade deficit. Once again, this may be reversing cause and effect. Exporting firms with higher import content in production and firms producing higher quality goods are more likely to survive in export markets (see Figure 2). Turkey needs more integration, not less, to upgrade quality and move up the value chain.

Commentary

European economic integration is the key to Turkey’s past and future

March 11, 2015