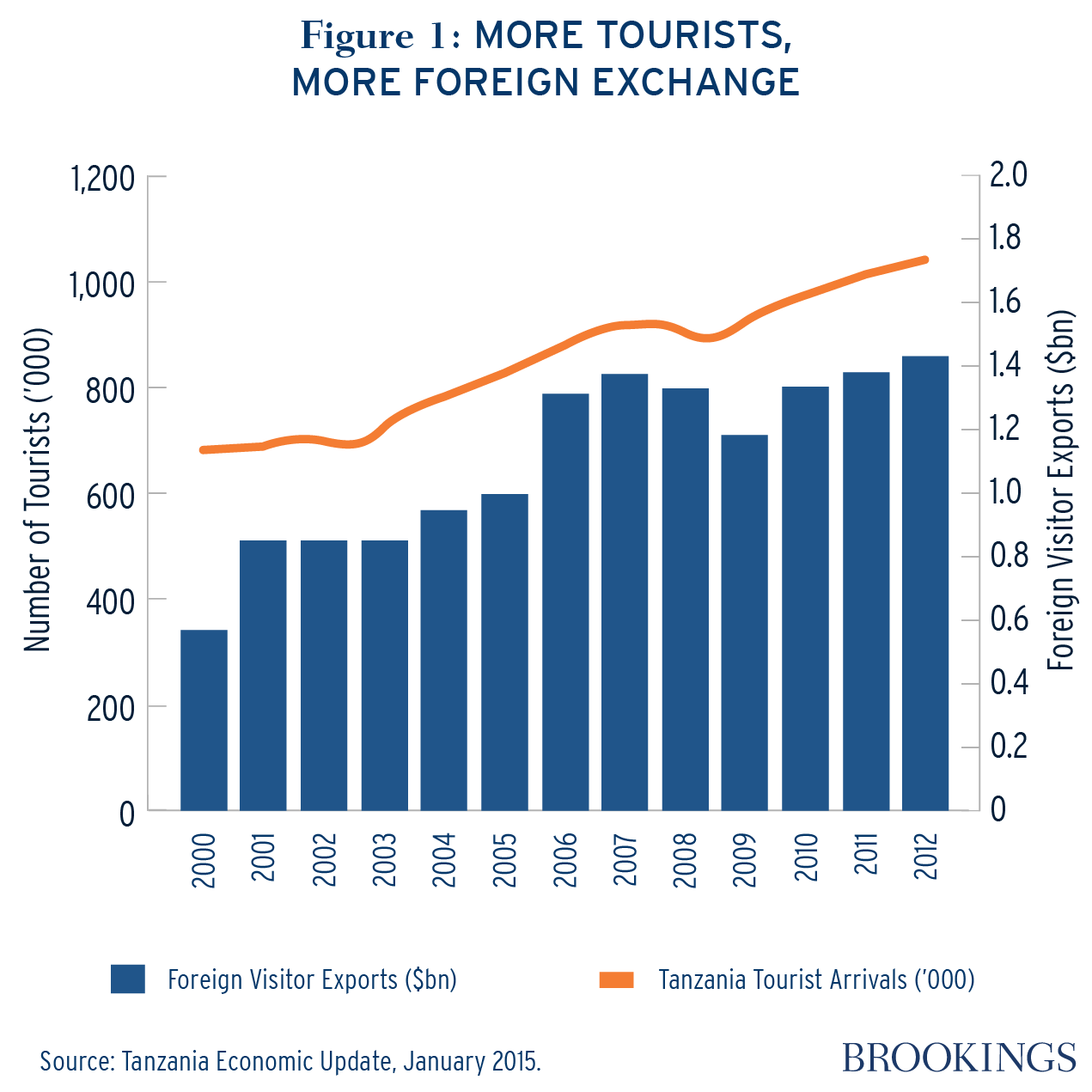

In 2013, Tanzania hosted 1 million visitors, generating almost two billion dollars (Figure 1). These numbers explain why tourism is at the top of the agenda of many playmakers in Tanzania. However, many Tanzanians have not seen the color of this money.

How can the tourism sector bring more benefits to more Tanzanians? The key is that visitors purchase more local goods and services, and that operators hire more local workers and pay taxes. Of course, these mechanisms are not self-supporting; poor services by local suppliers or excessive taxes can drive international visitors and investors to other destinations.

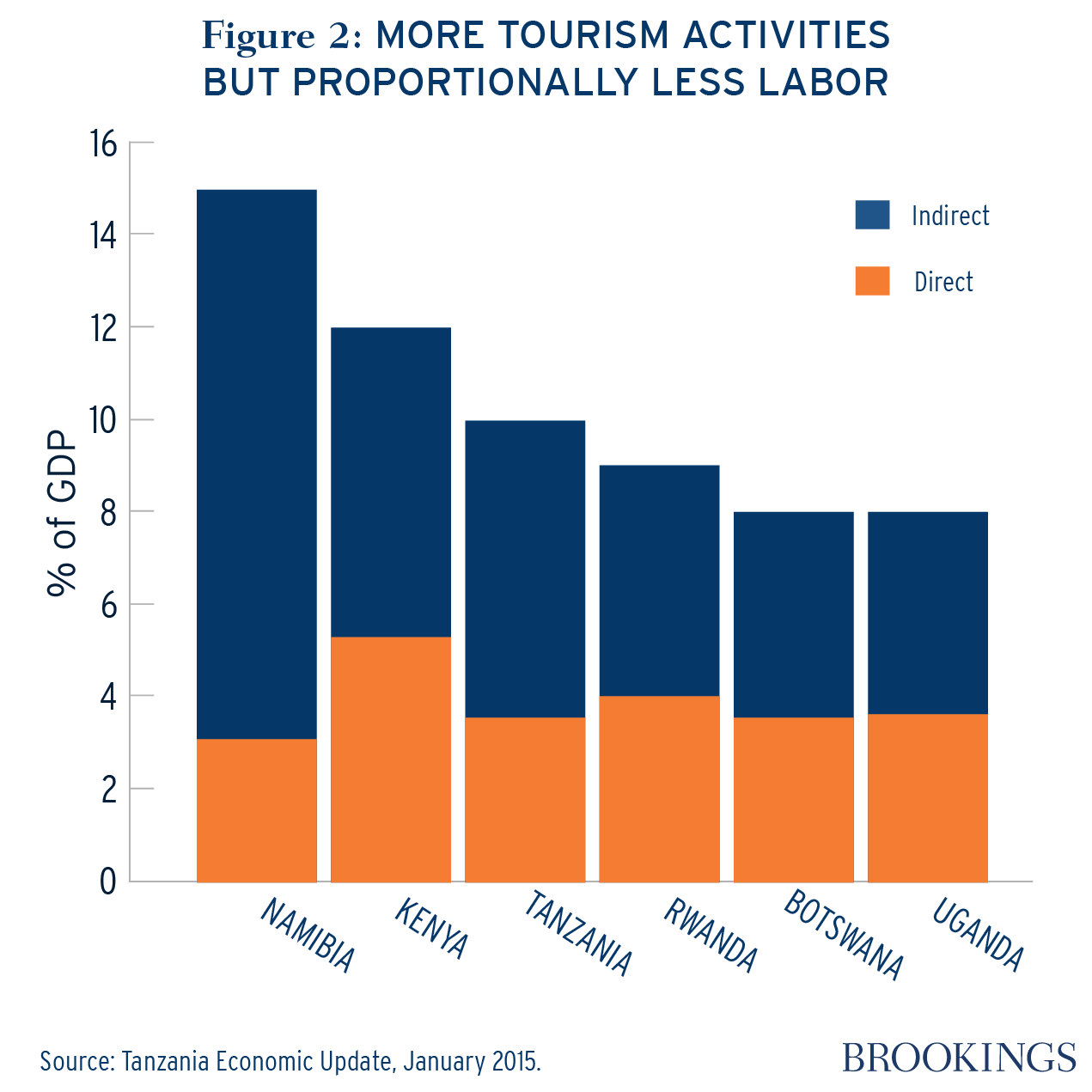

Indeed, recent experience in Tanzania has shown that enticing visitors to spend on the local economy and private operators to hire local staff may not be practical; hotels and restaurants in Zanzibar find it easier to bring in chicken from Brazil and many lodge owners rely on expatriate managers. This is also why the share of labor in tourism production has declined over the past decade in spite of the rapid growth of the industry (Figure 2).

Lack of quality is commonly cited as the problem for using local resources. High-end tourists, ready to spend thousands of dollars, demand top quality and may not be willing to compromise. Not only are unhappy visitors unlikely to return but they are very likely to share the unpleasant experience with friends and relatives who in turn may be equally put off.

The government benefits from the tourism industry directly through taxes and fees. After all, tourists enjoy public resources and should pay for this. Furthermore, tourists should also contribute to the treasury and thus, to schools and hospitals for better public services. However, in leveraging maximum benefits from the sector, the government ought to be careful to avoid so many taxes as to kill business. The revenues collected from taxes should also be used efficiently and transparently.

Unfortunately, Tanzania’s performance on taxes and redistribution mechanisms has been below par. The country’s current tax system is highly fragmented (with over 25 different taxes levied on tour operators), while the use of the revenues collected from the tourism industry is almost impossible to track. Take, for example, the revenues from hunting licenses that travel through various accounts including the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry account, the Treasury, the Tanzania Wildlife Protection Fund, local governments, and local communities. It is no surprise that even the Controller and Auditor General has not been able to confirm the utilization of these revenues.

Upgrading local skills and streamlining the tax system in tourism should be two priorities for Tanzania. Hiring and buying local will only happen if local workers and suppliers can match international standards. The temptation to make it mandatory to hire local managers or use local goods and services can provide short-term relief but it could be detrimental in the longer term. The success of Costa Rica, Tunisia, and several East Asian countries has demonstrated that joint programs between the private and public sectors can be very effective in upgrading skills and raising local standards. These programs range from establishing vocational schools for young Tanzanians interested in the tourism sector to providing technical assistance toward local community efforts aimed at upgrading the quality of their food production. Such programs do indeed exist in Tanzania, but only at a small scale. The challenge is therefore to transform these pilot projects into national initiatives that can really make a difference on the ground.

Streamlining the tax system is a must. Most private operators accept paying taxes to a system that is simple and fair. Simplicity reduces transaction costs (as it is always more expensive to pay multiple and complex taxes) and it also reduces the opportunities for illegal payments and corruption. Fairness? There is no worse feeling than to pay taxes or fees when others are not, explaining why so many businesses decide to remain or to move into informality. Last but not least, the Tanzanian government should make sure that the revenues collected from the industry reach their intended beneficiaries by streamlining the existing redistribution mechanisms and implementing credible checks and balances along the way.

Only by improving skills and taxation will the level and distribution of benefits from the sector increase. Nothing really new, but it is time for Tanzania to “walk the talk,” and accelerate her pace beyond her competitors so that an increasing number of citizens gain from the country’s bountiful natural resources.

Commentary

Tourism In Tanzania: The Elephant In The Room

February 3, 2015