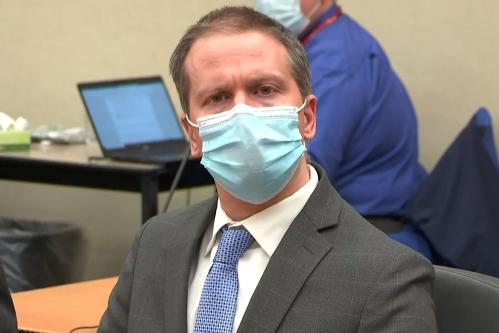

Derek Chauvin has now been sentenced for the murder of George Floyd. He has received a sentence of 270 months (22.5 years). How do we judge whether or not this is a fair decision?

Chauvin’s sentence is 120 months or ten years more than the presumptive sentence of 150 months (12.5) years set by the Minnesota sentencing guidelines and 7.5 years more than the trial Judge Peter Cahill could have sentenced him to while still remaining within the Minnesota guidelines. If Chauvin serves his sentence without getting into trouble, he can expect to be released from prison after 15 years, due to time off for good behavior. He could have expected release after 8 1/3 years, had he received the presumptive sentence for Murder 2.

While Chauvin’s sentence enhancement is substantial, is it substantial enough? The state asked for a sentence of 360 months (30) years, double the presumptive sentence, and many initially reported reactions suggest that Chauvin got off easier than he deserved. The argument most commonly heard for a stiffer sentence is that 15 years in prison, or even the full 22.5, is incommensurate with the harm Chauvin caused. Chauvin can expect some day to be released from prison. George Floyd will not be coming back. While in prison Chauvin will be able to talk to his friends and relatives, and they to him. George Floyd can talk to no one. His young daughter will grow up without a father’s love or support.

The argument that Chauvin got off too easy because George Floyd is gone forever is natural, appealing and legally irrelevant. Anyone guilty of second degree homicide has killed someone. None of their victims will be coming back or able to comfort grieving family members, and none will be there to support children who will forever miss them. These losses are baked into Minnesota’s sentencing scheme. The Minnesota legislature has decided that the ordinarily appropriate sentence for people who unintentionally kill others while intentionally injuring them is between 128 and 180 months in prison. Upward adjustments of up to 480 months or downward adjustments are possible based on the facts of the crime.

Although discretion often plays a role in criminal sentencing, Minnesota, a pioneering state in the sentencing guidelines movement, has attempted to confine judicial discretion within bounds set by law. Legislative judgments, as further specified by the Minnesota sentencing commission, provide standards for determining what a sentencing judge is and is not permitted to do. In the case of second degree murder, Judge Cahill could have issued any sentence that seemed appropriate to him, so long as it was no less than 128 months and no more than 180 months. To go above the 180 month limit, either the judge, with the defendant’s permission, or a jury, if the defendant so chose, had to find that the existence of aggravating conditions had been proven beyond a reasonable doubt. Some of these conditions have been specifically spelled out in Minnesota law, while others are judicial creations, consistent with legislative intent and approved by the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Derek Chauvin opted to have Judge Cahill rather than the jury determine whether any sentencing-enhancing conditions had been shown in the trial beyond a reasonable doubt. The prosecution argued that 5 such conditions existed:

- That Chauvin abused a position of trust and authority.

- That Chauvin treated George Floyd with particular cruelty.

- That children were present during the commission of the offense.

- That Chauvin committed the crime in a group with the active participation of other individuals.

- That George Floyd was particularly vulnerable.

The judge found that the first four of these, but not the last, had been shown beyond a reasonable doubt. This was not, however, the end of the judge’s factfinding. He still had to determine whether any of these factors so differentiated Chauvin’s actions from that of the typical second degree murderer as to justify a higher than guidelines sentence. He found that only the first two of these did. In doing so, he was aided by the parties’ briefs and by his own research on the law. There was nothing special about his approach to the issue. It was a serious attempt to look at legislation and case law. His memorandum explaining his decision reads very much like an ordinary lower court decision trying to make sense of statutes and precedent. This does not mean his decisions were pre-ordained or that another judge would have reached the conclusions that he did. But this is often true of lower court judgments. What matters more is that the memorandum describes a good faith attempt at evaluating facts and applying the law. Most likely it should be sufficient to sustain his judgments if the enhancements are appealed.

The problem that Judge Cahill faced was fitting the facts of this case to prior law since no decided case was parallel to this one. Most prior abuse of trust and authority enhancements had occurred in cases involving criminal sexual conduct or domestic abuse. The defense argued that the exception was limited to such cases or, to accommodate an unwelcome precedent, to cases in employment or employment-like contexts. Judge Cahill rejected the defense position, pointing to language in a prior case holding that the argument that a particular aggravating factor had not previously been applied to a particular class of defendants was an invalid defense.

Having resolved this legal issue, the judge still had to decide whether the circumstances in which this abuse occurred justified an upward departure from the guidelines. Did it, for example, matter that Chauvin was presumably acting within the scope of his authority when he first placed the handcuffed Floyd on the ground and attempted to subdue him. The need was to decide at what point Chauvin’s actions so abused any authority he had that they justified a beyond guidelines sentence. For the judge this point was reached when Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck beyond the time required to subdue him and was further shown by Chauvin’s twice rejecting suggestions by fellow officers to place Floyd on his side and by his failure to render aid or allow others to render aid, especially after Floyd had passed out.

Finding that Chauvin treated Floyd with particular cruelty and deciding on the implications of this finding required comparing this case with other ones where cruelty enhancements had been granted. Judge Cahill recognized that the cruelty of Chauvin’s conduct was “of a kind not usually associated with the commission of the offense(s) in question,” but that was only the beginning of analysis. Although defense argued that prior cases enhanced for this reason had often involved threats or taunting or assaults that had lasted for substantial amounts of time, Judge Cahill had no trouble justifying his conclusion that Chauvin’s actions met the standard for a substantial sentence enhancement on these grounds. He saw cruelty in the length of time Chauvin pinned a handcuffed and unresisting George Floyd to the ground, in Chauvin’s dismissive responses to George Floyd’s pleas that he couldn’t breathe, including his response on one occasion that “[i]t takes a heck of a lot of oxygen to say things,” and in Chauvin’s unwillingness to take his knee away after Floyd had become non-responsive.

Judge Cahill did not, however, mechanically assume that every aggregating factor he had found justified an upward departure from the guideline sentence. Although minors were present at the scene, he recognized that those who witnessed Floyd’s slaying were free to depart, and that their involvement was unlike that of the children in cases where upward departures had occurred. In those cases children had seen their parents sexually assaulted or otherwise violently attacked. Judge Cahill also recognized that the precise wording of the authorization for upward departures when a killer was part of a group raised legal questions which, although he didn’t say so, meant that he may have been mistaken in finding that this enhancing circumstance had been shown. Because he saw it as unnecessary, he did not attempt to grapple with the legal issue.

Judge Cahill, in addition, rejected an argument that Chauvin’s counsel made for placing Chauvin on enhanced probation, a dispositional rather than a durational departure from the guidelines. To the extent there was precedent for the motion, it was rooted in a case where a young first offender, whom the prosecutor had labeled “an outstanding citizen,” avoided a 24 month guideline sentence and was instead placed on probation for a burglary he committed while inebriated. The difference between that crime and Chauvin’s is enough to show that the motion had no chance of succeeding. Commentators have criticized it not only as absurd but also as likely to backfire by alienating the judge.

I doubt if the judge’s sentence was affected by this motion. I also think there was a reason why counsel made it, apart from technically preserving an issue for appeal. It was the only way that counsel could get on the record for the judge’s and the public eye information Chauvin wished to convey about his prior good character. The fact that Chauvin had no prior criminal convictions could not be advanced in arguing for a downward sentencing departure because the guideline sentence already reflected Chauvin’s lack of prior record. It could, however, be noted in an attempt at a dispositional rather than a durational departure, as could information about Chauvin’s past public service, commendations he had received and the like. But whatever Counsel’s intent, the argument backfired in the court of public opinion, even if it is unlikely to have affected Judge Cahill’s sentence.

When all is said and done, there remains an inescapable degree of discretion in the sentence Judge Cahill settled on, even though he tried to anchor his determination in existing case law. He referenced aggregate practice with respect to departures from second degree murder sentence guidelines, noting that when Murder 2 sentences were enhanced the mean enhancement for convicted killers with no criminal history was 278.2 months. He also referenced the only two cases he found where a defendant with no criminal history had received an elevated sentence because “abuse of a position of trust and authority” and “particular cruelty” were aggravating circumstances. Each of these cases involved particularly vulnerable victims—3-year old children—and the cruelty inflicted on these children was in the judge’s words “horrific.” In one case, as part of a plea deal, the sentence was 300 months, and, while it was greater in the other, that crime had been originally charged as first degree murder, with the charge reduced in a plea detail. Comparatively speaking, a sentence of 270 months for Chauvin’s crime appears reasonable.

Thinking about Minnesota law as it affects sentencing, one can conclude from Judge Cahill’s sentence that justice was done, even if one might have said the same thing had Cahill sentenced Chauvin to 20 years in prison, or 25. For those who nevertheless think Chauvin got off easy, there is another factor to consider. The defendant alluded briefly to it in his sentencing brief, but the judge ignored the issue for good reason. If Chauvin were released into the general population of a medium or maximum security prison, his prior profession and current notoriety might mean recurrent physical assaults and a likelihood that he would never leave prison alive. The situation might be different in a minimum security prison, but at least in the near term political considerations make such a placement unlikely. This leaves solitary confinement of the kind Chauvin experienced while awaiting sentencing as the most likely way to accommodate both safety concerns and the seriousness of Chauvin’s crime. Research indicates that extended solitary confinement is torture, and it has been shown to adversely affect the brain. Chauvin’s conditions of solitary confinement would not be like that of those who are placed in solitary for punishment. He is likely to be allowed more contact with the outside world than those placed in solitary for disciplinary purposes and to have access to reading materials, entertainment media and, to the extent feasible, other resources that would be available to him if he were part of the general prison population. Nevertheless, being alone in a cell, having limited exercise time and, for the most part, being unable to communicate with others will make any time Chauvin must serve in solitary particularly hard. He will not have gotten off easy.

Commentary

The Derek Chauvin sentencing decision: Is it fair?

July 1, 2021