There have been two serious efforts in the past half-century to impeach and remove a U.S. president from office. The first, which ended in 1974, led to the resignation of its target—President Richard Nixon. The second, which began in 1998 against President Bill Clinton, led to the resignation of the man who had orchestrated the effort—House Speaker Newt Gingrich.

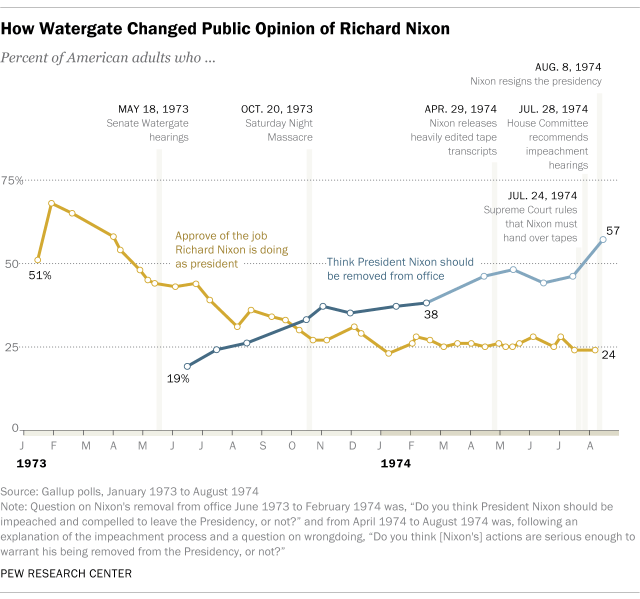

In the former case, opinion shifted steadily against President Nixon and in favor of removing him from office as the public reacted to swirling events at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue and learned more about the details of the Watergate affair. In the latter, new information had almost no impact on the views of the people about removing President Clinton, which they opposed from the beginning of this episode to the very end.

Now we have entered the early phase of a third impeachment and removal effort, this time directed against President Donald Trump. Will it lead to triumph or disaster for Democrats? Will it lead to the end of Mr. Trump’s presidency or pave the way for his reelection? We do not know. But history gives us clues about what to watch for along the way.

First, a president’s standing with the American people as the impeachment inquiry proceeds makes a big difference. As the Watergate hearings unfolded in the summer of 1973, soon followed by the infamous Saturday night massacre in the fall, President Nixon’s job approval fell steadily from 50% in the late spring of 1973 to just 24% at the beginning of 1974. During the next eight months, culminating in Mr. Nixon’s resignation, it barely budged. In short, Nixon was gravely damaged politically long before the House of Representatives voted to impeach him on three counts in July.

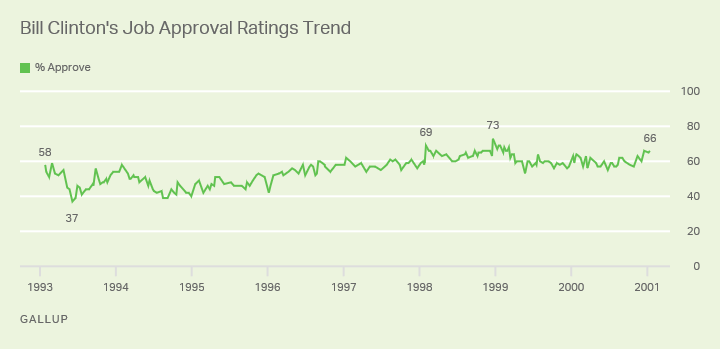

By contrast, President Clinton’s job approval, which stood above 60% at the beginning of 1998, never fell below 60% during that year, spiked upward to 73% at the end of the year, and stood in the high-60s as the Senate failed to approve either of the articles of impeachment in January of 1999.

A second key indicator is public support for the impeachment effort itself. As Chart 2 shows, public support for impeaching and removing President Nixon rose steadily through 1973, roughly doubling by the end of the year, and rose another 20 points from January to August of 1974.

In contrast, again, public support for impeaching and removing Bill Clinton did not budge through the summer and fall of 1998, despite congressional hearings, the explosive special prosecutor’s report, and approval of impeachment articles. On August 8, according to Gallup, 34% of Americans supported impeachment and 63% opposed it. The December 12 survey, which asked the same question word for word, found the identical result—34% in favor, 63% opposed. In the eyes of the American people, Clinton’s accusers had failed to make their case against him.

A New York Times/CBS News poll conducted after the House impeachment hearings and votes also found that these events had “no effect” on the public’s view of the proceedings against Mr. Clinton. Even after approval of articles of impeachment, nearly two-thirds said that the Senate should not put the president on trial but should instead work out a compromise, such as a formal censure. If a trial occurred, 68% said that the Senate should not remove him from office.

This is not to say that the public doubted the truth of the accusations against President Clinton. By the end of 1998, a majority of the American people had decided that Mr. Clinton had lied under oath, engaged in illegal acts, and abused the powers of his office. But as a December 1998 Gallup report concluded, the majority did not believe that these offenses “[rose] to the level of being impeachable.”

A third key indicator is the extent of bipartisan support for impeachment in the House of Representatives. When the House Judiciary Committee voted on impeaching President Nixon, 6 out of 17 Republicans supported the charge that he had obstructed justice, and 7 agreed with the charge that he had abused the powers of his office. This presaged the dramatic trip of a Republican senatorial delegation headed by Barry Goldwater to the Oval Office to inform President Nixon that support for him had collapsed, even among members of his own party. Informed that he would lose an impeachment vote and that the Senate would vote to convict him, Nixon resigned before either vote happened.

Events played out very differently in 1998. When the full House voted on articles of impeachment, only 5 Democrats out of 205 voted to support any of these articles. When the Senate voted on the two articles that had received a majority in the House, no Democrat supported either one, a result foreshadowed by the sharp partisan divisions in the House.

Measured against these three key indicators—presidential job approval, public support for impeaching and removing the president, and bipartisan support in Congress, where do matters stand as efforts to impeach President Trump begin in earnest?

Presidential job approval

An NPR/PBS/Marist poll conducted after Tuesday’s revelations but before the release of the whistleblower’s complaint puts approval of President Trump among registered voters at 45%, within the narrow band it has occupied for most of his presidency. Republican support for the president still stands at 90%. Two other polls, HuffPost/YouGov and Politico/Morning Consult, also found presidential approval remaining largely unchanged, with Republicans standing staunchly behind the president. If neither of these numbers changes as this saga unfolds, the Democrats will likely suffer the same fate as did the Republicans two decades ago.

Support for impeachment

The NPR/PBS/Marist survey shows a country sharply divided—along partisan lines—on the merits of proceeding. Overall, 49% support impeachment while 46% oppose it, figures that include 88% Democratic support and 93% Republican opposition. (In evidence of partisan intensity, 61% of Democrats “strongly” approve, while 80% of Republicans strongly disapprove.) 82% of Democrats regard this as a very serious matter; 85% of Republicans dismiss it as pure politics. Still, there are signs that the Republican wall of opposition may not be completely impregnable: 52% of Republicans think that the whistleblower should testify before Congress, and 27% regard the president’s telephone call requesting Ukrainian cooperation with an inquiry into Joe Biden’s conduct as a serious matter warranting further investigation.

A HuffPost/YouGov poll taken between Tuesday night and Thursday morning sheds some early light on the dynamics of a rapidly changing situation. There has been a modest uptick in public support for impeachment, from 42% to 47%. This gain is almost entirely attributable to increased support among Democrats, which has risen from 74% to 81% during the past two weeks. Support among Independents has remained stable in the mid-30s while declining among Republicans from 16% to 11%.

A Politico/Morning Consult poll, also taken between Tuesday and Thursday, found similar results. Although support for impeachment rose by 7 points, most of the increase is attributable to a 13-point jump among Democrats, and the country remains divided on the matter, 43 to 43, with 13% unsure.

Support for impeachment in the House

At this point, sentiment among House members divides starkly along party lines. More than 90% of House Democrats have indicated their support for an inquiry that almost certainly will culminate in articles of impeachment, while as of now, not a single House Republicans has come close to voicing support.

As many commentators have noted, a public statement by newly-elected moderate Democrats from swing districts helped crystallize pro-impeachment sentiment within the party. Based on a close analysis of the 1998 and 2000 election results, veteran analyst Ron Brownstein concludes that House Republicans who defied sentiments in their districts by voting to impeach President Clinton paid at most a modest price, suggesting that moderate Democrats may not suffer much either in 2020. On the other hand, the Monmouth survey looked at swing counties, decided by less than 10 points in 2016, and found that only 32% of voters in these contested areas supported the impeachment and removal of President Trump, with 60% opposed, while just 22% thought that the Senate was likely to remove the president after the House voted to impeach him.

The evidence suggests that these voters are right about the Senate’s likely response to articles of impeachment. Senate Republicans have remained mostly in lockstep behind Mr. Trump since he assumed office. Of the 53 Senate Republicans, 45 hail from solidly red states. Of the remaining 8, just 4—Susan Collins of Maine, Cory Gardner of Colorado, Martha McSally of Arizona, and Tom Tillis of North Carolina—will face the voters in 2020. Most Senate Republicans need fear primary challenges but not serious general election contests. Unless sentiment about President Trump shifts sharply among Republicans in their states in the coming months, their political calculus points toward sticking with him. The imponderable factor in this equation is the number of Republican senators who will decide to buck the preferences of their supporters in favor of what they have decided is the constitutionally required course of action.

Persuading the public to support impeaching and removing a president is a two-step process. The public must be convinced that the charges are true—and that they are weighty enough to justify overturning the results of a presidential election. Mr. Nixon’s accusers met both these tests, and he was forced to resign. By contrast, Mr. Clinton’s accusers met the first test but not the second. As the Senate trial began, 79% of Americans thought the president had committed perjury and 53% that he had obstructed justice, but only 4 in 10 believed that either charge warranted Clinton’s removal from office. The Senate vote fell far short on both counts of the indictment, and their target served out the rest of his term as a popular chief executive.

As the impeachment effort against President Trump gets underway, the American people are divided on both these tests, and his accusers must meet a weighty burden of proof. It remains to be seen whether the Democrats’ announced determination to proceed swiftly to impeachment will give the people enough time to assimilate new information and perhaps change their minds.

Commentary

Impeachment and public opinion: Three key indicators to watch

September 27, 2019