Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) announced recently that he plans to scale back the chamber’s traditional August recess from four weeks to one. But will the Senate actually remain in session during the dog days of summer?

McConnell’s stated reason for keeping the Senate in town involves its workload; there are appropriations bills to be passed and presidential nominees, including judges, to be confirmed, he argues. But it’s unclear if accomplishing either of the goals requires keeping senators in Washington. While senators may claim that they want to follow “regular order” and take up individual spending bills, institutional factors are working against them. As Peter Hanson has argued, the Senate is less likely to hold individual votes on spending bills when the majority party is small, divided, and distant from its minority colleagues. With Republicans holding only 51 seats (only 50 of whom are regularly voting, given John McCain’s (R-Ariz.) illness) in a polarized chamber, keeping members in session may do little to actually advance McConnell’s stated goal.

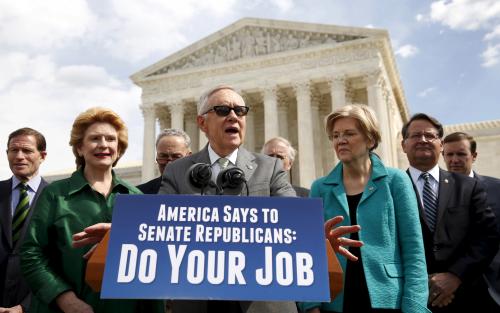

On nominations, meanwhile, what McConnell may actually be in the market for is a deal. Last summer, during the first of what were to be two “extra” workweeks, McConnell and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) reached an agreement to confirm dozens of nominees without recorded votes and with that, the Senate left town, losing only a few days of the originally scheduled recess.

Will Schumer agree to such a deal again? One key potential difference that may affect Schumer’s calculations this year versus last involves the type of nominations to be considered. Last year’s nominations push focused on confirming non-judicial nominees; none of 73 nominees confirmed without a recorded vote during the Senate’s extra time were for district or appeals court seats. (One judge, Kevin Newsom of the 11th Circuit, was confirmed during that week, but only after a cloture vote and a recorded vote on confirmation.) On one hand, we might expect lifetime judicial appointments to be more politically salient—especially in an election year—making Democrats less willing to accept a confirmations-for-recess trade. Many of Trump’s judicial nominees, however, have received some support from Senate Democrats. Between January 2017 and June 1 of this year, 37 judges were confirmed by the Senate with recorded votes, with an average of 23 Democrats voting in favor. (Independents who caucus with Democrats aren’t included in this calculation.) Democrats did frequently “run out the clock” on these nominees—that is, insist that all time for debate allowed under the rules pass before holding a final vote. But given the willingness to vote for many of the underlying nominees, it’s not clear that Democrats would insist on staying in town to consume similar time in August if a reasonable deal was on the table.

The electoral landscape also suggests that a nominations deal might be sufficient to save the recess. Of the 35 Senate seats being contested this fall, 26 are held by Democrats and only 9 by Republicans; the set of seats Democrats are defending include 10 in states won by President Trump in 2016. By keeping the Senate in Washington, many have argued, McConnell will be keeping these senators off the campaign trail, making it more difficult to defend their seats. As a result, some Democratic senators may value time in their districts enough to agree to confirm a number of nominees in exchange for maintaining the recess. At the same time, however, those same senators may be willing to skip votes on which they are not pivotal in exchange for time in their states, believing that their constituents won’t punish them for a handful of missed votes. This combination—Democrats’ desire to campaign and a potential willingness to miss some votes to do it—may increase McConnell’s willingness to make a deal for what he really wants: confirmed judges.

Commentary

Will the Senate actually stay in Washington this August? Ask again later

June 12, 2018