On March 18, 2018, a young Black man named Stephon Clark was killed by police in my hometown of Sacramento, California. He was unarmed, standing in the backyard of his grandmother’s home, and he was shot eight times. The disturbing body camera footage and the resultant social media outcry have become an excruciatingly common part of contemporary news, but the events themselves are, in many ways, as old as America. In a new paper, my coauthors and I situate the Black Lives Matter movement in a centuries-long history of targeted state repression in Black communities, and of Black organizing to document and resist that violence.

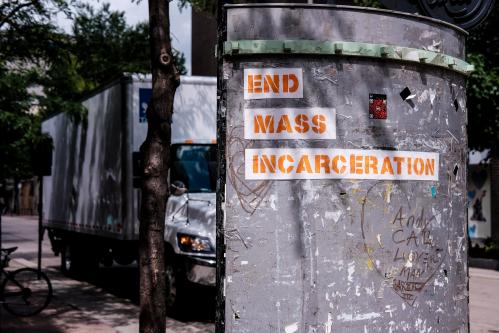

The scope of the criminal justice system in the United States is unique among developed democracies, and almost unique among nations. Over two million people are incarcerated in America, almost one in one hundred adults, with about five million others on probation or parole. The people who bear the brunt of the criminal justice system are disproportionately Black. There is documented racial inequity in police stops, in sentencing, and in deaths at the hands of police.

These statistics are no accident of history. Major expansions of the criminal justice system came in intentional reaction to advancements in the civil rights of Black people. For instance, when the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery, an exception was made for those being punished for a crime. Southern states responded by creating new laws against crimes of poverty, such as “vagrancy,” that shuttled thousands of poor people, and especially poor Black people, into a new system of forced labor. Convict leasing, as it was called, made up a critical component of the Jim Crow system intended to strip black people of the political and economic gains made during Reconstruction. So, too, was the racial terror campaign of lynching, which—tolerated and sometimes abetted by law enforcement—killed nearly four thousand Black people in the South between 1877 and 1950.

Just as long as the history of repression is the history of its resistance. One of the galvanizing issues in the long campaign for civil rights was protection against state-sanctioned violence; anti-lynching campaigns made up some of the earliest work of the NAACP. The Black Lives Matter movement should be understood as the latest iteration of this history, a modern counterpart to the campaigns of Ida B. Wells.

In a new paper, my coauthors and I document how Black Lives Matter (BLM) has responded to police violence. We hope other scholars will make use of the data we assembled, including information on 780 Black Lives Matter protests that occurred in 44 states and 223 localities. We find that BLM protests were more likely to occur in localities where more black people have previously been killed by police. The correlation holds even when controlling for a wide array of other factors, including the size of the city, the size of the local black population, poverty, education and other factors that might influence a community’s capacity to protest.

The result demonstrates that, at least under some conditions, localities can respond to the most extreme aspects of the carceral state with increased political engagement. One might expect that communities that have experienced more frequent deaths at the hands of police might be especially unlikely to take the risk of public protest. Instead, we find evidence of mobilization. This is especially important given the role the carceral state plays in disenfranchisement.

The next step in our research agenda is to assess how and where Black Lives Matter activism has shaped political views and policy change. For instance, do larger or more frequent protests correlate with the passage of police reforms? Are Americans’ attitudes about the police different after a local protest has occurred?

There could even be electoral outcomes. In Sacramento, Clark’s death has mobilized BLM activists to campaign against the local District Attorney, Anne Marie Schubert, who is up for re-election this year against criminal justice reform advocate Noah Phillips. Schubert is a Republican running for re-election in a blue county. To date, she has not filed charges against the police officers who shot Stephon Clark. In response to nonviolent Black Lives Matter protests outside, the District Attorney erected a fence around her office. But, while we know that communities with a history of police violence were the most active sites of “Black Lives Matter” protests, it remains an open and critical question whether and when those protests translate into political change.

Commentary

New data show that police violence predicts Black Lives Matter protests

May 17, 2018