This post is part of series by Brookings experts on Trump in 2018.

Election night 2016 was demoralizing for the Democratic Party. Though they picked up two Senate seats and six House seats, they lost the presidency and continued to be relegated to minority status in both chambers of Congress. Democrats who woke up on that Tuesday confidently believed they were heading to the polls to see through the inevitable: electing the first woman as president of the United States. Those Democrats, however, went to bed shell-shocked by the reality that Donald Trump would succeed Barack Obama.

The reaction to Mr. Trump’s election was swift, and among Democrats 2017 was the year of the resistance, as protests and marches became routine. As the president’s popularity fell throughout his first year in office, the voices of opposition grew in number and intensity. The resistance of 2017 will also lead to an energized Democratic Party, ready to fight back.

Data already show that Democrats are done drying their tears and are standing up and doing something: they’re mobilizing. Record numbers of people are running for office, donations are soaring, political action committees are training volunteers and would-be candidates. And while there was a schism in the Democratic Party, still raw from the presidential primary battle, one man has risen and shown that his leadership alone is powerful enough to unite the Democratic Party.

That man is President Donald Trump.

Mr. Trump was elected to office as a popular vote loser. While he is not unique in that regard—the last Republican president was as well—he lost the popular vote by a larger margin than any president in American history. That lays the foundation for many Americans to be unhappy with the Electoral College winner. However, popular vote-losing presidents can have some first-year successes. George W. Bush did. At the end of his first year in office, aided in large part by his response to the 9/11 terror attacks, President Bush’s job approval rating stood at 87 percent.

Mr. Trump has done nothing, nor has anything happened, that would increase his popularity since he took office. In fact, his highest job approval rating was in his first month in office and his popularity has declined since. As the chart below shows, President Trump has the lowest job approval rating of any president at the end of his first calendar year in office since the Second World War. Such a lack of popularity is and can be dangerous for a president’s broader legislative agenda. But more to the point, that unpopularity damages the electoral prospects of president’s party in Congress.

With few exceptions, presidents lose seats in a midterm election. Unpopular presidents can see massive swings in their party’s electoral fortunes. Bill Clinton in 1994 and George W. Bush in 2006 saw their parties lose majorities in both houses of Congress and Barack Obama saw the Democrats lose the House in 2010 and the Senate in 2014. In each case, those presidents had higher approval ratings in the days before those wave elections than Mr. Trump has right now. Those realities have led the Cook Political Report’s Charlie Cook to say that 2018 is shaping up to be a wave election. Though approval ratings and reliable cycles of discontent are just a popular subset of indicators, a healthier sampling of the political environment only strengthens the claim.

Concerning the federal level, voters are responding by openly wanting a change in party control in Congress. Over the past few weeks, Democrats have set records in their advantage in what is called the ‘Generic Congressional Ballot’—a poll asking people which party they want to control Congress. As the table below shows, Democrats currently have between a 9 and 18 percentage point lead over Republicans.

| Generic Congressional Ballot | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Poll | Democrat-Republican | Advantage | Date |

| CNN | 56-37 | D+18 | Dec. 20 |

| Reuters | 39-27 | D+12 | Dec. 20 |

| Economist/YouGov | 44-35 | D+9 | Dec. 20 |

| Quinnipiac | 52-37 | D+15 | Dec. 19 |

| NBCNews | 50-39 | D+11 | Dec. 17 |

| PPP | 51-40 | D+11 | Dec. 14 |

| Source: RealClearPolitics | |||

Evidence of Democratic mobilization persists in elections at the state level. In Virginia, Democrat Ralph Northam outperformed expectations, winning the governor’s race by nine points, while Democrats made historic gains in the Virginia House of Delegates—a recount of the sole outstanding race ended in dramatic fashion, leaving the chamber split right down the middle. In a special election for a Tennessee state senate race last week, a Republican won by only two points in a district Donald Trump carried by over 40 points.

| Special House Elections | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seat | Republican vote share, 2017 | Republican vote share, 2016 | Vote Swing |

| Ga. 6th District | 51.8 | 61.7 | R-9.9 |

| Kan. 4th District | 52.2 | 60.7 | R-8.5 |

| Mont. At-large | 49.7 | 56.2 | R-6.5 |

| S.C. 4th | 51.0 | 59.2 | R-7.8 |

| Utah 3rd | 58.0 | 73.5 | R-15.5 |

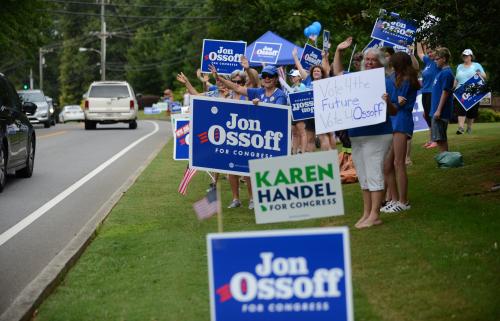

Even in U.S. House special elections, Democrats have outperformed expectations. While they came up short, the formerly demoralized Democrats showed the ability to recruit quality candidates and run competitive campaigns in reliably Republican districts. As the table above shows, in the given special House elections this year Democrats swung the electorate by between 6.5 and 15.5 percent. Most of these special elections happened because of vacancies due to presidential appointments, a risk Republican leaders likely wouldn’t take in districts they didn’t feel confident retaining.

In those special elections, Democrats, in many cases, recruited high-quality candidates who were disciplined (even if newcomers) and effective fundraisers. The ability to recruit candidates, however, was not isolated to a few off-time elections. Party organizations and political action committees are reporting huge increases in interest among potential Democratic candidates for Congress. In October, Michael Malbin wrote on this blog about both the number of Democratic challengers relative to previous years and the fundraising capacity those candidates have shown early on. He noted, “These numbers tell us that Democrats are poised to take advantage of a wave if one develops. And based on past experience, a wave election would likely sweep out some incumbents who are not yet even challenged.”

Reports from the liberal group EMILY’s List that recruits and funds female candidates for a variety of offices have shown the impact of the women’s resistance movement thus far. The organization noted that they are expanding in order to gear up for 2018. Part of the decision to expand was based on a figure that should scare Republican officeholders: 16,000 women reached out to their organization with interest in running for office! Many of the same women who participated in a march in Washington, DC, the day after the presidential inauguration—filling the nation’s capital with crowds that dwarfed the president’s the prior day—are no longer marching. They’re running.

Taking advantage of this political enthusiasm will require an organized and well-funded party. If 2017 is any indication, the two central campaign committees most responsible for midterm elections—the DCCC (Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee) and the DSCC (Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee)—will be able to support challengers and shore up incumbents in every state and district. First-quarter fundraising blues have quickly become record-breaking hauls as Democrats react to life under Mr. Trump. The DCCC—the House half of the team—has outraised its Republican counterpart (the NRCC) for seven consecutive months, amounting to a $15M edge as of the latest FEC filings.

A competitive edge in fundraising doesn’t necessarily signal enthusiasm up and down the board, though. Sometimes it’s just a few wealthy, well-connected bundlers or transfers from members of leadership with massive war chests. But the DCCC’s fundraising operation has been propelled by an online program that managed to surpass its 2015 total—itself a personal best—by May this year. Through September, about 40 percent of donations to the DCCC came from online fundraising, typically between $17 and $20 each, and a full 60 percent came from donations under $200. Small-dollar donations generally signal grassroots energy and eventually turnout, and it’s clear Democrats have an abundance as we approach campaign season.

Finally, the Democrats appear as unified as a habitually fractious party can be. The Democratic Party’s Unity Commission, established by the 2016 Democratic Convention to sort out party issues between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders supporters, finished its work in December amid expressions of unity (to the surprise of many.) Intraparty conflict remains 2016’s most enduring collateral effect on the Democrats. But the respective political institutions have broken bread, and this makes unity moving forward all the more likely.

So a wave is inevitable, right? Not quite. Yes, it’s true that the White House and congressional Republicans have done themselves very few political favors over the past year. They have fumbled top agenda items like “repeal and replace” and an ever-receding version of “the wall.” They have solidified a public impression of corruption, racism and amateurism while producing a nearly-constant negative news cycle. It’s no surprise the fundamentals all point towards a Democratic resurgence.

However, Republicans have plenty of time to reverse this course with their own voters, and Democrats have plenty of time to mishandle the bounty they have been given. Republicans will surely begin with a messaging campaign to recoup the public opinion drag from tax reform. While House Speaker Paul Ryan’s “wonkiness” is surely overrated, he has been effective at messaging and institution-building within the party. Yet, these tactics are unlikely to shrink, in absolute terms, the broad base of Democratic enthusiasm. No party likes to be in incumbent protection mode, but eleven months from the midterms, Republicans face real challenges while Democrats transfer resistance into mobilization.

Commentary

Trump in 2018: The year of the mobilized Democrat

December 27, 2017