The UK’s Liberal Democrats are the lineal descendants of the Liberal Party, which held power under leaders such as Gladstone, Asquith, and Lloyd George and led the country for much of the half-century preceding World War One. After the rise of the Labour Party in the 1920s, the Liberals kept the flame alive as a third party that enjoyed more affection than popular support—and more popular support by far than seats in parliament.

After joining forces with a breakaway Labour faction, the Liberals saw their share of the popular vote rise to 25% in 1983, although Britain’s first-past-the-post district system gave them less than 5% of the total seats. By 2005, however, they had tripled their representation in Parliament to 62 seats. And after holding their gains in the 2010 general election, they entered into a coalition government with the Conservatives, who had received the most votes but had fallen well short of a parliamentary majority.

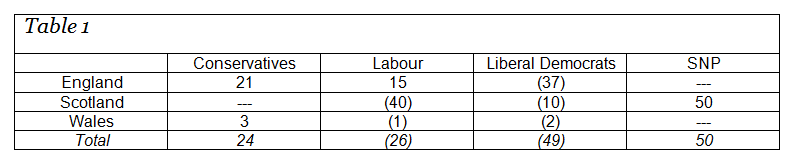

For reasons that my colleague Richard Reeves explored in his FixGov post earlier today, this alliance worked out poorly for the Liberal Democrats. In yesterday’s general election, their share of the popular vote fell by nearly two-thirds from 23.1% to only 7.9%, and their parliamentary caucus collapsed from 57 seats to only 8. The LibDems lost 37 of their 43 seats in England, 10 of 11 in Scotland, and 2 out of 3 in Wales. Their long-time leader Nick Clegg held his seat but resigned his leadership post this morning.

Where did the vanished support for the LibDems go? The answer points to the structural implications of the 2015 elections.

Overall, only a small share of the LibDems’ 15- point popular vote loss ended up in the hands of the major parties: Labour’s share increased by only 1.5 points, the Conservatives’ by a scant 0.8 points. Most of the gains accrued to the principal minor parties: taken together, the vote share of the Scottish National Party (SNP), the United Kingdom Independent Party (UKIP), and the Green Party rose from 5.7% in 2010 to 21.1% today. Although the Conservatives did manage to gain a slim majority of the seats in parliament, the vote share of the two major parties is continuing its downward course, shifting British politics ever closer to the multi-party European model.

The distribution of the seat gains and losses was even more significant, as Table 1 below shows:

In theory, the shift of Scottish LibDems seats to the left-wing SNP could have accrued to Labour’s advantage—if Labour had made a strong enough showing in England. On the eve of the election, the polls suggested that Labour was in a good position to challenge the Conservatives’ grip on at least two dozen English seats. In the event, however, Labour netted almost no Conservative seats: of Labour’s 15-seat gain in England, fully 12 came from LibDem constituencies. If Labour cannot narrow the huge edge that the Conservatives enjoy among English voters, its chances of regaining power anytime soon are remote. And if Labour continues its leftward shift, it is hard to see how it can expand its support.

The ability of the Conservative to surmount the surge of support for the anti-immigrant, anti-Europe UKIP was impressive. It is as though the Republicans had maintained their majority in the House of Representatives despite the decision of its Tea Party faction to form an independent party. But the Conservatives have promised to hold an in-or-out referendum on its membership in the European Union by 2017, a pledge its leader, the once and future Prime Minister David Cameron, repeated in his victory speech this morning.

Within Mr. Cameron’s next and final 5-year term, then, Britain will make two fateful decisions—one about dealing with the upsurge of Scottish nationalism, which will require a substantial measure of devolution and new constitutional arrangements, the other about the upsurge of English nationalism, which could lead to its exit from Europe. The election debate this year may have been petty and dull; its aftermath will be anything but.

Commentary

UK elections: Where did support for the Liberal Democrats go?

May 8, 2015