The one big piece of America’s financial picture that is ripe for reform is tax expenditures. Tax expenditures are provisions of the federal income tax code favoring specified sources or uses of income. Right now they are not part of the budget process but they should be. And here’s why.

In a real sense tax expenditures function like spending programs, designed to promote the provision of publicly valued goods. In some policy areas, tax expenditures are the major form of government subsidy. For instance, of roughly $280 billion in federal spending and tax expenditures for housing in FY 2012, tax expenditures accounted for more than three-fourths of the total, most notably the mortgage interest deduction, other homeownership exclusions, and low income rental housing tax credits.

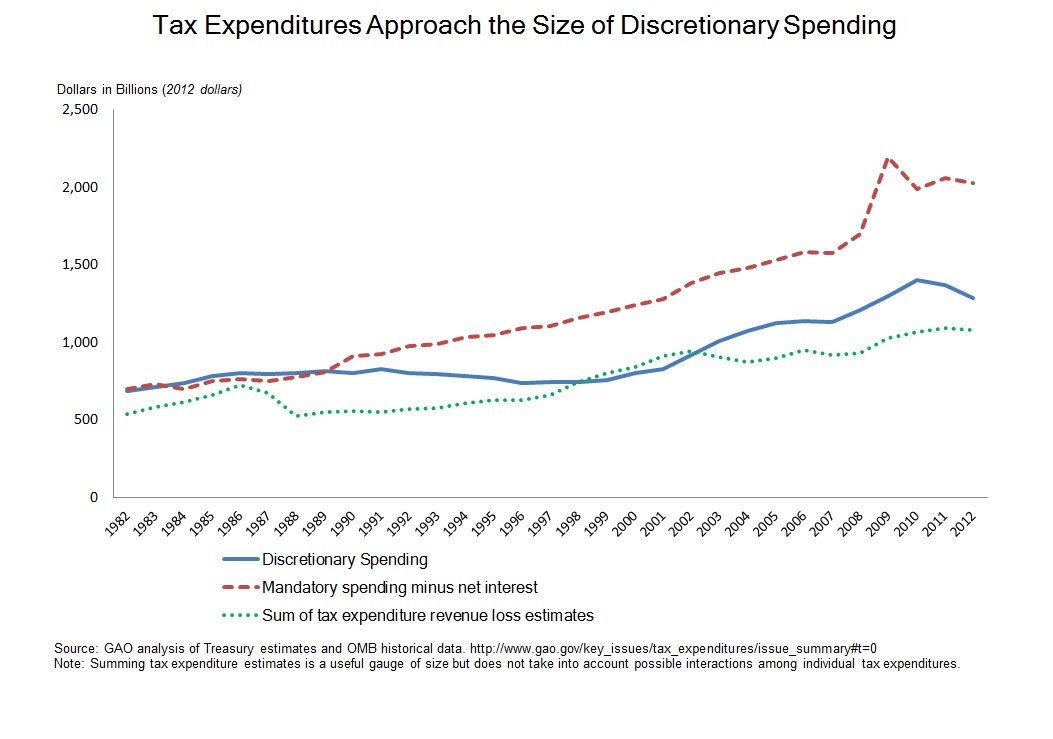

Over the years tax expenditures have quietly assumed major fiscal significance. Donald Marron estimates that they constitute over $1.1 trillion in revenue losses for the income tax alone in FY 2012 — 31 percent of total federal spending, or nearly as much as total discretionary spending that year.

While new tax subsidies are subject to PAYGO like entitlement spending, their invisibility and institutional isolation makes them less subject to review and competition than other forms of spending. They arise in an entirely separate policy world centered in the revenue committees and the Treasury, considered apart from comparable spending programs that share common objectives and purposes and that are part of the budget process. Because they are separate they are not subject to the extensive reviews that regular spending programs come under. HUD, for instance, says little in its annual performance report about the low income housing tax credit, even though it is the single largest federal housing supply program.

Leaders in both Congress and the Adminstration have strong incentives to resort to tax expenditures rather than direct spending to pursue their policy objectives. Tax expenditures give proponents the ability to both create new benefits and tax cuts at once while not appearing to increase spending. And those who doubt government’s administrative capacities may prefer to use tax expenditures, which unlike administered spending programs may be directly claimed by taxpayers, free of pesky review and oversight by federal bureaucrats.

Tax expenditures should be reviewed as part of the budget process for several reasons.

First, excluding them from possible cuts means other parts of the budget assume disproportionate shares of deficit reduction.

Second, to hold revenues constant, tax rates have to be higher to cover the costs of subsidies provided through the tax code.

Third, tax provisions often subsidize activities taxpayers would undertake anyway, thus yielding no new policy impact. Because the income distribution of these incentives is ‘upside down,’ they disproportionately benefit those in higher brackets, who are likely to undertake favored activities without the tax break, whether it be saving for retirement, sending their children to college, or buying health insurance. Yet, tax subsidies are not efficient vehicles to influence the behavior of low income people, nonprofits or states and localities with little or no tax liability means direct spending tools are more capable of reaching these groups of taxpayers.

Fourth, to the extent that tax expenditures succeed in shifting investment, many economists argue they reduce economic efficiency by tilting investment toward tax-favored activities, crowding out unsubsidized investments that would yield higher economic returns. Huge examples are housing and health care, two economic sectors whose size and growth are undoubtedly fed by the tax subsidies.

With little coordination between tax subsidies and related spending programs, it is not surprising that overlap and inconsistencies emerge. GAO found that the welter of federal grants, loans, guarantees and tax subsidies for higher education offset one another in unpredictable and confusing ways.

Regular review of tax expenditures should be integrated into the federal budget process. Here are some options:

Accounting – Honest accounting looks through the form to the substance of transactions. In this spirit, tax expenditures should be recorded as outlays and revenues should be raised by the same amount. As Burman and Phaup argue, this would ensure a more honest accounting of these subsidies without changing the estimated deficit.

President’s budget formulation – OMB should include tax expenditures in its reviews alongside spending, inviting Treasury into the review sessions. Tax expenditures should be presented in the budget as alongside direct spending.

Portfolio budgeting – OMB should develop comprehensive budgetary portfolios capturing all federal resources, including tax expenditures, for selected missions and cross-cutting goals. Already working to improve performance for nine government-wide goals such as export promotion and workforce training, OMB should take the next step: budgeting government-wide for those nine areas and possibly others (see Peterson-Pew Commission on Budget Reform).

Agency performance reviews – Tax expenditures should be subject to performance planning and measurement under the framework of the Government Performance and Results Act by substantive agencies with a vital programmatic stake in the outcomes from tax expenditures. OMB and Treasury should work together to ensure that agencies include these subsidies in performance plans and performance reviews.

Congressional budgeting – Fragmented committee jurisdictions complicate integration of tax expenditures into the congressional budget process, but the barriers are by no means insuperable. Just as budget resolutions and reconciliation instructions call for action by authorizing and appropriations committees, such vehicles can be used to prompt review of tax expenditures. Options include:

- As part of a broader reform to strengthen the leadership’s role in the process, chairs of the tax writing committees could be included with appropriators and others in developing a multi-year budget resolution that directs committees to coordinate their annual budget-related actions affecting policy objectives.

- Tax expenditures should be reported alongside program spending in the allocations for each of the 19 budget functions in the budget resolution.

- Budget reconciliation should provide savings targets to revenue committees requiring reduction of selected tax expenditures.

Without tax expenditures, the federal budget process is missing a true picture of the impact of government on policy. Including tax expenditures into the budget process would go a long way towards providing a complete look at federal spending.

Commentary

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Mysterious Case of Tax Expenditures

February 6, 2014