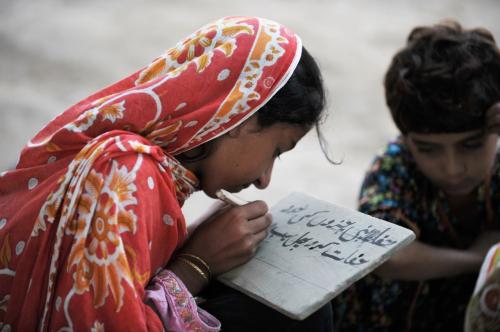

Ayla recalls her early days in Sindh, Pakistan at school, when it was nothing but a strange building. Her home was so different and so was her neighborhood.

I remember my teacher, Ms. Sindhu, who lived three houses away from mine, once asked me to narrate a story about a camel ride. We have many camels around us, so I became excited and wanted to share, but I just couldn’t. I just struggled to say what I knew, what I have enjoyed and wanted to say. It felt like my tongue froze.

Ms. Sindhu asked Ayla to narrate this story in English, a language that was unfamiliar to her at the time. If asked in Sindhi, Ayla would not only have communicated her experience but also received her teacher’s energy of affirmation in return. Language is an invisible source of familiarity in school that children hold on to—it is through language that they have experienced the world so far. In this way, language becomes a bridge between school and home, allowing children to safely cross between the two worlds.

Despite the abundance of literature and experience supporting the benefits of teaching in a familiar language, an estimated half of all children in low- and middle-income countries are not taught in a language they understand. The case of Pakistan is no different. After 200 years of colonial rule under British India, Pakistan was born in 1947. Today, the country is home to over 70 languages, including the official languages of Urdu and English (a language that stayed, even after the British left). Urdu and English are utilized by the government, corporate sector, media, and—most relevantly—educational institutions.

As is the case with many other post-colonial nations, Pakistan is afflicted with “English-medium fever,” a desire to keep English as the medium of instruction in schools due to its perceived superiority and association with wealth, status, and power. This fever has led to a deep disconnect between the languages of the home and the school. Only 2 out of over 70 indigenous languages are formally recognized in schools in Pakistan. Most of the other languages remain “informal” in their usage, given little to no recognition outside of everyday use.

It is crucial to continue to longitudinally study the effects of such solutions, to identify what’s working and what can be potentially scaled up, and ultimately, to create a world where Ayla and the millions of children like her can learn and share their experiences with confidence, ease, and excitement.

Despite the desire for English-medium instruction, for most students “English-medium” schooling only means that the textbooks and exams are in English. Research has demonstrated that a large portion of teachers in Pakistan do not understand English. Instead, teachers rely on local languages to teach and communicate with students, and students memorize and replicate text without comprehension. Students are subjected to learning unfamiliar content in a foreign language by a teacher who has not mastered the language. This places a burden on students, thereby furthering the inequality between themselves and more privileged students.

The gap between policy and practice in the language of instruction

Pakistan’s national education policies provide provinces with the option to use native languages in the early years of schooling and encourage the inclusion of mother tongues.

This leads us to ask why Pakistan’s national policies are not inspiring practice within provincial and private school systems. If the intention to teach children in languages they understand is there, why are a significant numbers of schools continuing to teach children using textbooks in Urdu or English, despite those languages collectively only being the native tongue of 8 percent of the population?

One crucial gap is that while policy details the importance of learning in one’s own language, there is no guidance on how this policy should be implemented. School systems are left on their own to design curriculum and develop the necessary material to implement this policy. Moreover, the examination boards for Matric and Intermediate students are still held predominantly in Urdu and English, thereby discouraging schools from investing in teaching children in familiar languages and instead facilitating the rote memorization of unfamiliar language textbooks that students will later replicate on exams. Parents also fear that their children will do poorly on these exams, lose opportunities if they study in their own language, and forgo learning in the English language.

This is contributing to a growing crisis where children are attending school but struggling to comprehend. When these children decide to no longer pursue an education, we say they “dropped out.” But the truth of the matter is that these children are pushed out due to a systemic failure.

A language ladder can help bridge multilingual instruction

Languages can provide access to opportunities and serve as a bridge between a child and the outside world. However, to ensure academic success, cognitive development, and positive identity formation, children must be taught in languages familiar to them. Research finds that after children have developed proficiency in their familiar language(s), it is easier for them to learn foreign languages like English. Conversely, learning in an unfamiliar language is too demanding for a young child. This disadvantage disproportionately impacts children facing other educational barriers, such as poverty, hunger, and poor learning conditions.

So, how can a mother tongue-based multilingual education policy be translated into the classroom? To answer this, The Citizens Foundation, which operates one of the largest networks of independently run, nonprofit schools in the world, began a research study in 2018 that includes a socio-linguistic survey, interviews and focus groups with stakeholders and experts, and literature reviews. We combined more than five years of research findings to develop a “language ladder” (or language progression plan) that outlines how children can be taught in their native language in the early years and then transition to learning multilingually to optimize learning and future opportunities (see image below).

The language ladder can be adapted to any context; all it requires is that a thorough socio-linguistic survey be conducted in the community to ensure that the aspirations and needs of the community are understood and are reflected in the language progression plan. The development of a language ladder is a first step toward teaching children in languages they understand.

TCF is currently piloting this language ladder across 19 schools and 84 classrooms—from pre-KG to grade 2—in Tharparkar, Pakistan. It will be scaled to close to 100 schools in the upcoming school year. The model adopts the most familiar language as the medium of instruction in the early years (until grade 3), undergoes a gradual transition from familiar to unfamiliar language in the late primary and early secondary years (grades 3 to 7), and finally completely transitions to the language most demanded beyond schooling in the late secondary years (grade 8 onward).

Source: The Citizens Foundation.

The multilingual language ladder puts comprehension at the center. It insists on the use of a familiar language to teach unfamiliar content so that there is a higher likelihood that the student will thrive in their environment. To ensure this goal is achieved, it is not enough to develop a policy that simply endorses mother-tongue instruction. There is also a need for technical guidance as to how multilingual schools can implement such policy on a classroom level.

Designing and introducing a language ladder can support policymakers and practitioners in addressing multilingual teaching within their individual contexts. It is crucial to continue to longitudinally study the effects of such solutions, to identify what’s working and what can be potentially scaled up, and ultimately, to create a world where Ayla and the millions of children like her can learn and share their experiences with confidence, ease, and excitement.

You can learn more about the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Program at The Citizens Foundation here and a recent policy brief related to school language policy here.

Photo credit: Albertina d’Urso.

Commentary

‘Language ladders’ show promise for introducing multilingual instruction in classrooms

December 22, 2022