To view the PowerPoint slides from the Annual CIES meeting on investing in early childhood development, click here.

The Annual Meeting of the Comparative International Education Society (CIES) took place virtually from April 25-May 2. Although the participants missed the Seattle coffee and beautiful environs that the in-person event would have provided, there were rich discussions held on Zoom under the umbrella of this year’s theme, “social responsibility within changing contexts.” Our four organizations—the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, the ECD Action Network (ECDAN), UNICEF, and World Bank—presented together on how to support countries to equitably and efficiently invest in early childhood development (ECD), including early childhood education (ECE), through various complementary resources and tools.

Strengthening public finance for ECD to deliver results at scale and to protect progress made in recent years is critical. As explained by the World Bank at the start of the session, despite the overwhelming evidence and political momentum built around ECD in the last decades, over 43 percent of children under the age of 5 are at risk of not fulfilling their full developmental potential due to risks of poverty, poor nutrition, and a lack of access to basic services and early enrichment opportunities. In low-income countries, 8 out of 10 children are missing out on ECE opportunities, and less than 2 percent of the overall education budget was allocated to the pre-primary subsector. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has made young children even more vulnerable as services have been disrupted, and parents and caregivers face an increased burden as they become frontline responders in the crisis of care and learning.

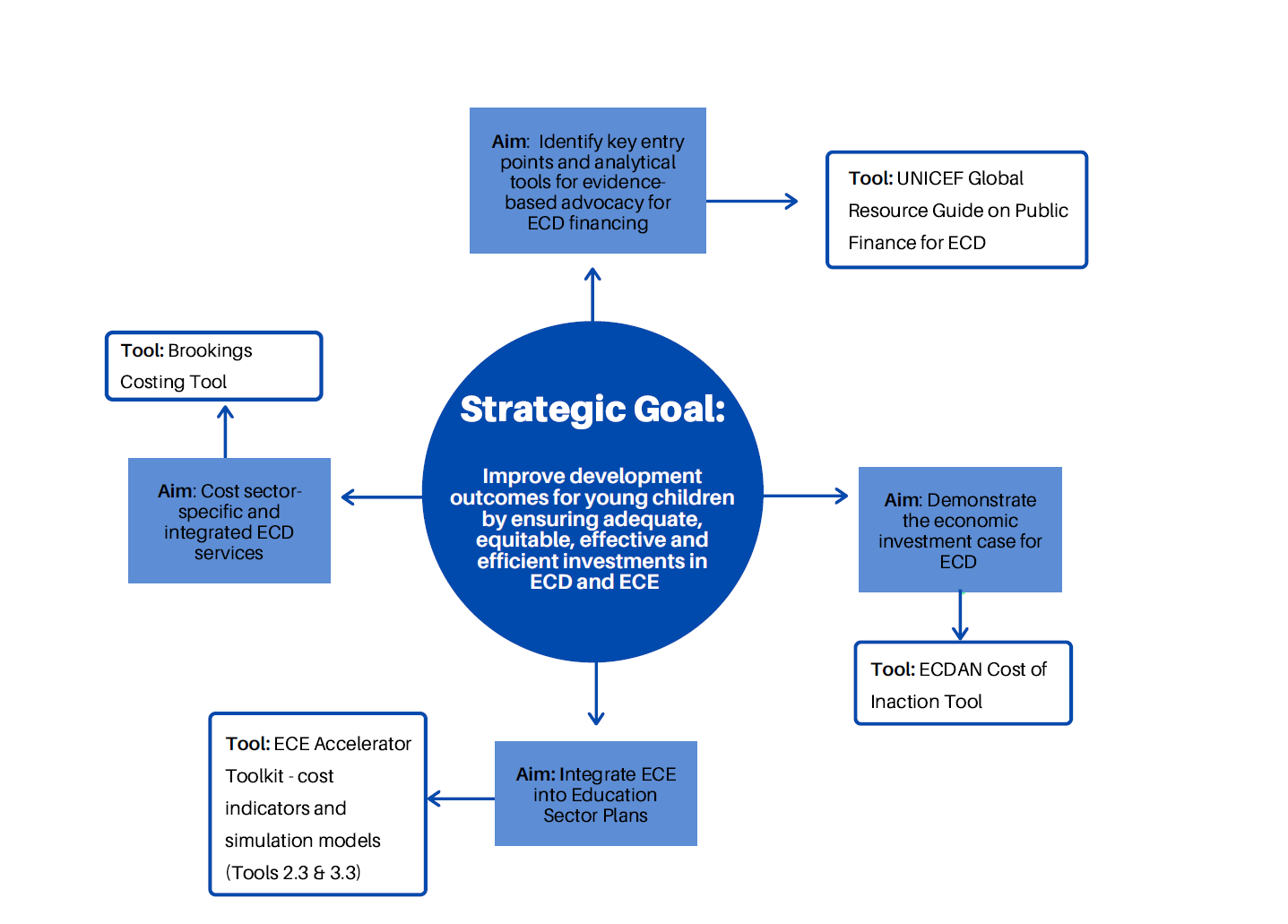

While multisectoral interventions for young children and parents are essential for providing comprehensive opportunities for ECD, these interventions can be difficult to plan, estimate costs, and monitor, as they cover a wide range of services, sectors, and government agencies. Understanding the financial costs and socioeconomic benefits of these services is essential to protect and promote ECD financing as countries grapple with the fiscal crisis wrought by the pandemic. The guidance documents and tools presented in our CIES session and described below demonstrate how the ECD community has worked together to provide concrete solutions to the many pressing ECD and ECE challenges (see infographic below).

Public finance for ECD

The first guidance document, the “Global Resource Guide on Public Finance for ECD,” shared by UNICEF’s ECD and social policy teams, aims to increase government, civil society, and other partner capacity to address financial obstacles and deliver at-scale and sustainable ECD results. It explains how to analyze and diagnose public finance issues in different country contexts, describes core actions and key analytical tools (e.g., costing estimates and public expenditure reviews) to support governmental budget decisionmaking and coordination, as well as provides case studies and examples. The guide also highlights the importance of ensuring that evidence-based efforts target key decisionmakers, including ministries of finance and planning, by generating the “right” evidence and using language that resonates with them.

Mainstreaming ECE into education system planning

Another resource, the ECE Accelerator Toolkit—developed as part of an innovative initiative between UNICEF and the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) to mainstream ECE within Education Sector Plans (ESPs)—was shared by the UNICEF education team. Officially launched in February 2021, the toolkit seeks to promote sustainable systems of quality pre-primary education, and is a globally relevant, interactive, and practical resource to help countries elevate ECE’s focus in ESPs, and thereby address SDG target 4.2. The presentation focused on the two costing and financing tools from the toolkit, which are used in education sector planning and budgeting processes to advocate for domestic resource allocation:

- Tool 2.3 features key cost indicators and drivers related to public costing and financing of ECE.

- Tool 3.3 provides guidance on the use and development of simulation models to create and compare alternative ECE programming interventions and prioritize policy choices. Specific country examples of “need-based projections”—driven by intervention targets (Sao Tome and Principe)—and “intervention-based projections”—driven by intervention components (Lesotho)—are included.

Costing education and ECD

The Brookings team presented its work on costing ECD and education, including a summary of its soon-to-be launched, publicly accessible online cost calculator. This tool, based on the earlier Standardized ECD Costing Tool (SECT) developed in collaboration with the World Bank in 2015, allows policymakers, donors, program implementers, and researchers to enter costing data in a guided survey form that provides a range of calculations, estimates, and simulated costs for both ECD and K-12 interventions. The calculator can inform effective investment decisions such as:

- Is the project feasible within a given budget?

- What are the cost implications of a programmatic change, such as in dosage or scale?

- How do the costs of intervention A compare to those of intervention B?

- What is the cost per beneficiary of an intervention or program?

- How are costs distributed across cost categories, resource types, and/or one time versus recurrent costs for this intervention or program?

Costs of inaction in ECD

A fourth tool, which measures the cost of inaction in ECD or the benefits foregone by not investing in children, was presented by ECDAN. This online “plug and play” tool compares costs to potential monetizable social benefits of an intervention. These benefits are measured in terms of increased individual income that one may receive over a lifetime, based on the intervention’s positive impact on the human capital development of children, such as improved health or cognitive development, which have compounding effects throughout a child’s life. This analysis contributes to the economic rationale for investment in ECD and can help compare different forward-looking scenarios to inform policy decisions—and can be particularly valuable to countries advocating for prioritization of ECD investments in the wake of COVID-19. It can be used to evaluate ECD interventions across different sectors, is available for use in more than 180 countries, and is currently being tested in Brazil and with UNICEF in Madagascar, and Bulgaria.

Together, these complementary guidance documents and tools—developed in a consultative process across several institutions—have enormous potential to greatly strengthen ECD policy interventions and resource allocation decisions. These efforts can greatly improve equitable access to quality ECD and education for the many children impacted today by COVID-19 and for generations to come.

To view the PowerPoint slides from the Annual CIES meeting on investing in early childhood development, click here.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The methodology for the Cost of Inaction Tool was developed by Jere R. Behrman, Florencia Lopez Boo, and Claudia Vazquez.

The authors would like to thank Maya Elliott at UNICEF and Sarah Osborne at the Center for Universal Education for their contributions to this presentation and blog.

Commentary

4 tools to protect and enhance investment in early childhood development and education

Reflections from the Annual CIES Conference

May 10, 2021