School closures and remote learning have propelled children’s ability to learn independently to the forefront of every busy and stressed out parent’s wish list. This ability, often described by education experts as “student agency,” has long held a privileged place in a range of reform movements aspiring to help students develop the breadth of skills needed for a fast-changing world. When young people are actively engaged in what they are learning, they develop a stronger mastery of content and become more creative and critical thinkers. For one thing, learning how to learn is fast becoming an essential skill for any young person—regardless of socioeconomic background—who will need to enter the world of work and navigate multiple shifting jobs over the course of his or her life.

But the ability to learn independently, as many parents around the globe found out amid pandemic-schooling, is not necessarily a skill that every child brings to his or her schoolwork nor one that every school purposefully cultivates. For starters, schools need to give students the space to practice self-directed learning, which is difficult if every minute of the school day is scheduled and directed by adults. Children are learning all the time, as any expert in child development will tell you, but they may not be learning what the adults and educators in their lives want them to learn. The trick is for schools to find teaching and learning approaches that channel students’ natural capacity, using innovative teaching and learning approaches that make lessons relevant to students’ lives, afford them the ability to apply classroom content to the real world, and iterate and experiment with others.

While there are many schools and organizations around the globe that have long practiced and advocated for teaching and learning approaches that employ innovative pedagogies and put student agency at the center, they have until now remained the exception rather than the norm. The question is: will the COVID-19 pandemic help change that? In particular, will parents’ recent insight into their children’s learning be a new driver for change? Many parents from rural communities in Botswana and India to urban centers in the United States and the United Kingdom have seen up close—and likely for the first time—inside the black box of classroom activities. Will parents’ unprecedented exposure to children’s education shape their beliefs about what a good education looks like over the long term?

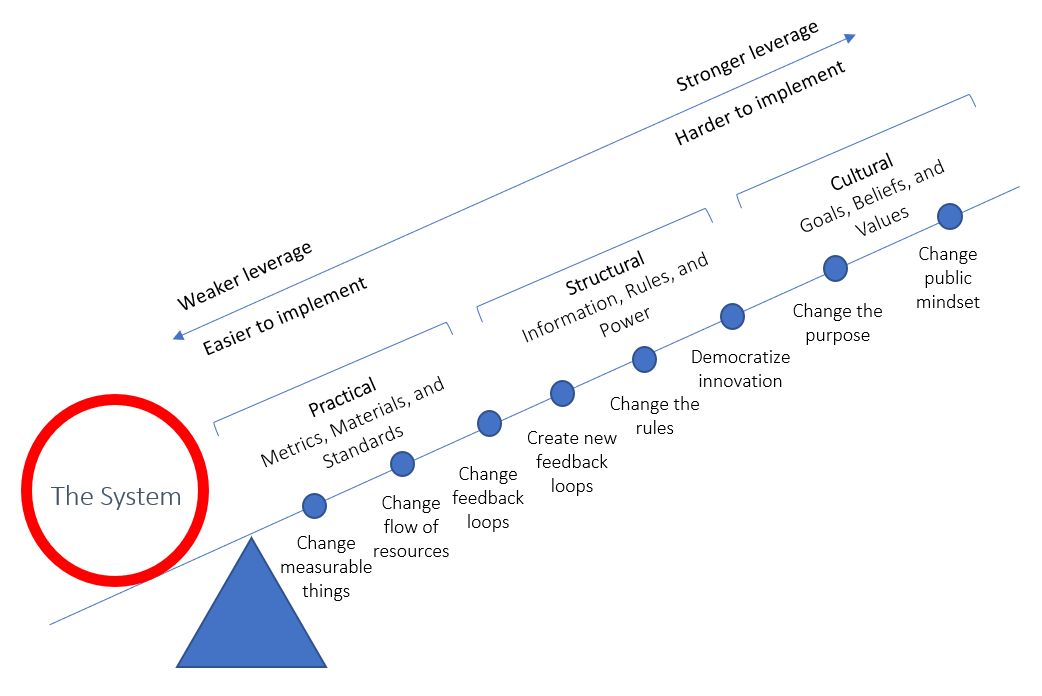

Parents, caregivers, and families beliefs about the purpose of education should be a strong lever for change. Donella Meadows, a seminal figure in system dynamics, argues that there are a range of leverage points for transformation. All are important but not all are equally powerful. For example, changing the flow of resources can remove constraints and is very important, but changing the collective mindsets around the purpose of a system is one of the most high-value leverage points for transformation. Figure 1 portrays a simplified version of Meadows’ classic framework, and we can see that increased family engagement in education has the potential to influence important cultural and structural leverage points. This includes everything from shaping the public vision on the purpose and goals of education to creating new flows of information and feedback loops that substantively bring important but often ignored actors, namely families, to the table.

Figure 1. Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system

Evidence for the important role of parent engagement in education

Until the novel coronavirus pandemic, the global education community spent comparatively little time thinking about the role of parent engagement in education, often focusing most of their attention on pressing topics such as teacher professional development, school finance, curriculum reform, and student assessment strategies. In fact, a quick scan of the education research in March 2020 found over 220,000 citations since 2001 with the search term “teachers,” approximately 57,000 with the term “parents,” and only around 6,500 citations with the term “parent attitudes.” One U.S. foundation supporting work on parent engagement estimates that only 4 percent of the U.S. philanthropic funding to education prior to COVID-19 went to family engagement.

But in March 2020—the month when almost all of the world’s countries shut their school doors—engaging parents moved quickly to the top of the agenda. Educators and education leaders around the globe developed new and creative ways of substantially engaging parents in their children’s learning. The state of Himachal Pradesh in India pivoted to an electronic parent teacher meeting strategy in which the vast majority of students’ families and caregivers participated. NGOs Pratham in India and Young 1ove in Botswana used SMS messages and phone calls to support parents as essential interlocutors helping their children stay engaged in learning by, for example, sharing activities and problems students could do around their homes that involved math. The Cajon Valley Union School District is using community liaisons to meet with parents, specifically parents whose children are in Kindergarten and are English learners, on a weekly basis to maintain meaningful relationships with families to directly support their children’s academics. Liaisons also ask parents to watch a short daily video teaching children letter names and sounds via song. Parent education hotlines were set up in western Pennsylvania and Buenos Aires, Argentina giving families an easy and accessible place to seek advice, get information, and connect to needed educational resources.

These innovative strategies emerged out of necessity but are likely to prove beneficial after the pandemic subsides. The evidence around family engagement in education, much of which comes from the United States, shows that more trusting relationships between families and schools are an essential foundation for building productive partnerships. It also shows that parents and caregivers can be an important ingredient in children’s achievement in school. When parents are involved and supportive of their children’s learning at home by, for example, asking questions about their children’s schoolwork, all children—but especially children who are from marginalized and low-income communities—benefit. With involved parents at home, children are more likely to attend, complete, and do well on academic achievement.

As the world contemplates a new year with the potential of a COVID-19 vaccine and a return to normalcy, there is a risk that this much welcomed transition would mean a departure from the innovative and helpful education strategies that have emerged amid the pandemic. Shuangye Chen, associate editor of East China Normal University’s Education Review journal, recently emphasized this risk, noting that as China is emerging out from under the pandemic, education systems seem to be reverting to pre-COVID-19 ways of operating.

CUE’s family engagement in education work

It is in this context that we at the Center for Universal Education (CUE) are delving deeply into the topic of parent and family engagement in education. We see the wide range of different emerging approaches—some tried and true, others new and novel—that could hold great potential for building stronger learning ecosystems for young people. We are interested both in strategies that build the strong relationships needed to help students advance along traditional academic measures but also the potential of this moment to build family and community demand for an educational approach that puts student agency and the range of accompanying 21st century skills young people need to thrive at the center of systems.

Our family engagement in education project* is grounded in the global research we have done on harnessing education innovations to “leapfrog” or accelerate education progress so that all young people, not just the lucky or well-to-do, are given education experiences that help them thrive in work, life, and citizenship. We are pleased to embark on this effort together with 16 project collaborators representing jurisdictions and organizations across 10 countries: Argentina, Australia, Botswana, Canada, Colombia, Ghana, India, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Together, with our Family Engagement in Education Network, we are surveying parents and teachers, conducting focus groups, documenting promising family-school engagement strategies, reflecting on how to harness this moment to emerge stronger than before COVID-19, and developing a playbook for decisionmakers from government, civil society, and funders to implement these strategies.

Ultimately, we see this work as an important contribution to the global effort to transform education so it can provide all young people with the skills they need to thrive in work, life, and, citizenship in the 21st century. In the long term, the impacts of this project could help enable parents to better support their children’s learning, teachers and schools to better understand the perspectives of parents and develop effective ways of collaborating, and policymakers to transform education in their jurisdiction to more effectively work with parents. In the long run, demand from parents and their children for the types of teaching and learning experiences that characterize a 21st century education is one of the best ways to enable sustained system transformation in education.

As we embark on this work, we will provide regular updates along the way. We welcome colleagues around the world who are grappling with these issues and who have questions to reach out to us. If you have insights on how COVID-19 has changed engagement with students’ families or what new family engagement practices and/or policies have resulted from COVID-19 that will continue after the pandemic is over, please do share—we would love to hear from you.

*The family engagement in education project examines primary caregiver’s beliefs about education. The project defines primary caregivers as the adult who assumes the most responsibility in caring for the health and well-being of the child. Thus, terms like parents, caregivers, legal guardians, and families are used interchangeably throughout.

Note: The author is grateful to her colleague Todd Rose for the robust discussions they have had on system transformation and education.

Commentary

Can new forms of parent engagement be an education game changer post-COVID-19?

October 21, 2020