Data is crucial for education planning and student monitoring, all the way from the classroom to the education ministry. Without relevant data, teachers and officials cannot adapt their methods to contextual problems and children will not develop to their full potential. What is less evident, however, is how governments can promote rigorous assessments across a broad spectrum of domains and use the data to actually improve education. With the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, building the bridge between data collection and learning outcomes is the key to ensuring that “access plus learning” does not exist in rhetoric alone. This requires expanding the emphasis from more traditional academic domains such as literacy and numeracy to include the skills children and youth need in a changing world—creativity, critical thinking, conflict resolution, social skills, and responsible citizenship, among others.

Over the past year, the Learning Metrics Task Force (LMTF) has helped 15 Learning Champions collaborate to develop their educational assessment capabilities and improve their knowledge of how to use the amassed data. Under the LMTF framework, the Buenos Aires Ministry of Education and UNICEF gathered education experts together for a meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina this past August to discuss how teaching, learning, and assessments can be improved to promote quality learning for all children. Representatives came from over a dozen countries, including nearly all Latin America countries and the Learning Champions from Ethiopia, Kenya, Zambia, Ontario (Canada), Bogota (Colombia), and the host, the city of Buenos Aires. The participants came together to learn from each other about how to tackle assessment challenges common to all education systems.

At the meeting, the Buenos Aires Ministry of Education presented its innovations and achievements from the past five years. Drawing upon the trio of guiding questions of the LMTF consultations, the ministry focused on three facets of its education system: 1) what is worth learning? 2) how can we teach it? and 3) how can we tell that learning is actually occurring to further inform teaching practices? Although there is no single solution to improving learning, the experiences of Buenos Aires demonstrate a possible path forward to achieve the goals set out for the next 15 years.

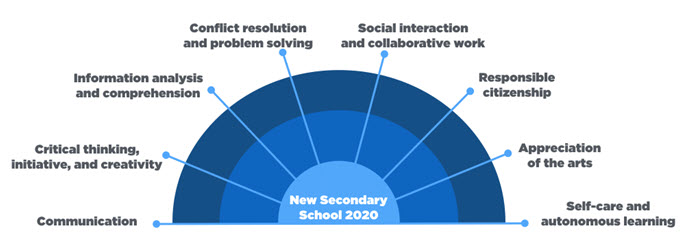

As the first part of its three-pronged approach, Buenos Aires has initiated a comprehensive curriculum reform through a consultative process involving students, teachers, superintendents, families, education experts, and public officials. The ministry included an adaptation of the seven LMTF domains of learning into the new secondary school curriculum and is working towards including them at the primary school curriculum in the near future. Thus, the students of Buenos Aires will learn a wide variety of skills to prepare them for the challenges of the 21st century.

Figure 1. The Buenos Aires adaptation of the seven domains of learning

Note: The eight domains identified for the City of Buenos Aires’ Nueva Escuela Secundaria (New Secondary School) 2020 include communication; critical thinking, initiative, and creativity; information analysis and comprehension; conflict resolution and problem solving; social interaction and collaborative work; responsible citizenship; appreciation of the arts; and self-care, autonomous learning, and personal development. Source: The Buenos Aires Ministry of Education.

Buenos Aires recognized, however, that changing what should be taught will not improve learning unless how it is taught is also changed. Teachers are critical to the success of the reform process, and Buenos Aires has worked hard to ensure that teachers are directly involved at every level of change. At Escuela de Maestros, the teacher training institution of Buenos Aires, teachers are trained in ways to teach and assess 21st century skills across the new curriculum.

In keeping with the reforms in curriculum and teacher training, Buenos Aires also updated its evaluation tools and capacity in order to understand fully the state of learning in the city. The Ministry of Education began its assessment reforms by first creating a decentralized Unit of Education Assessment and Evaluation. The unit makes information accessible and useful for the entire education community: at present, for example, it is working with teachers to familiarize them with education data and train them in using data to understand what and how students are learning. Escuela de Maestros has designed trainings for teachers that are tailored to specific areas where data from assessments have shown the need for improvement. The unit is also developing the capacity of education administrators to use data to identify areas across the curriculum that need to be improved.

By synthesizing these key portions of the education system, the city of Buenos Aires is connecting assessments to better learning outcomes. The assessments themselves are linked directly to the curriculum, teachers are trained in both areas, and the Unit of Education Evaluation ties all three approaches together and continuously informs the Ministry of Education on the efficacy of its policies. Thus, when a school is assessed, principals and teachers can use the resulting data to adapt instruction to the school’s specific needs; when an entire district is assessed, the ministry can adapt its approach according to the district’s strengths and challenges. Symbiotically combining curriculum, teacher training, and assessments allows Buenos Aires to promote better learning.

The city of Buenos Aires has pursued important education reforms over the past five years inspired by the Learning Metrics Task Force, the exceptional community of the LMTF Learning Champions, and multiple practitioners and specialists from all over Latin America and the world. These connections were crucial to the accomplishments of those goals; their support and experiences provided invaluable knowledge for our own policies. For that reason, a learning network was proposed this past August to ensure all children learn what they need to become the architect of their own futures in a changing world. The hope now is that we all continue to work together to improve learning outcomes for these children.

Commentary

How Buenos Aires adapted the LMTF seven domains to improve the relevance of secondary education

November 5, 2015