Inflation affects the price of everything we buy these days, and a college education is no different. But everyone pays the same price for eggs. Not everyone pays the same price for college. The availability of need-based financial aid means that those who can afford more pay more and those with fewer financial resources pay less.

As college prices rise with inflation, everyone will likely pay more, but will that burden be shared equally? In the current environment, there is reason to believe that price increases may be greater for those who can afford it the least. Such an outcome would be unfortunate given the role that higher education plays in promoting social mobility.

Sticker price vs. net price: Who pays what?

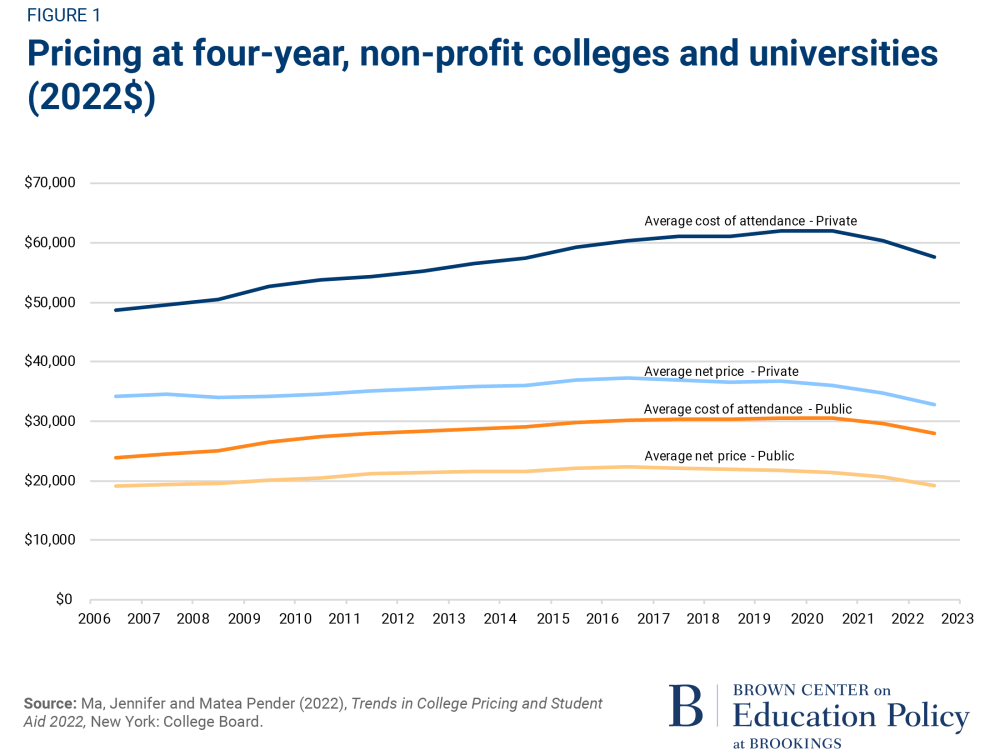

Even before the latest bout of inflation, public attention has focused on the “skyrocketing” cost of a college education. It almost tripled between 1979-80 and 2020-21 at four-year public and private institutions even after accounting for inflation over the period. The pace of growth has slowed, though. Between 2006-07 and 2019-20, the full cost of attendance jumped 27% at both types of institutions

But most students pay less than the full cost of attendance, sometimes labeled the “sticker price.” They receive some form of financial aid, reducing their price. The resulting amount they actually pay is labeled the “net price,” which equals the sticker price less grant-based aid. The only students who pay the full sticker price are those who are not eligible for financial aid. They mainly come from higher-income families.

Tracking net prices over time provides a different picture of the trend in college costs. Overall average net prices have risen at a considerably more modest pace. Between 2006-07 and 2019-20, they rose by 13% and 7% at public and private four-year institutions, respectively. But the average net price for all students includes those who receive financial aid and those who pay full price. We know that the latter group has experienced larger price increases. This means that the rate of increase in net prices for those who receive financial aid has to be lower than this national average.

How recent inflation affects college revenue

Then inflation hit in the wake of the pandemic. Academic year inflation, from July to June, hit 5.3% and 8.5% in 2020-21 and 2021-22, respectively. But institutions adopted moderate price increases, and some froze tuition. This was partly due to the lingering effects of COVID-19 recovery and partly due to public pressure regarding “skyrocketing” college costs (though this pressure may have been misplaced; see above).

After accounting for inflation, college prices are now dropping. In the last three years, the cost of attendance and average net price at public and private four-year institutions have actually fallen by around 10%. This is good news for students, both those with higher and lower incomes.

That trend may not continue, though. Lessons learned from the experience of the Great Recession may be relevant here. Inflation was low, and even negative at points, during the recession. But institutions struggled to make ends meet. Public institutions lost state funding and endowments at private institutions shrank. But a college’s bills need to be paid. To replace lost revenue, institutions raised sticker prices and cut financial aid, increasing net prices as a consequence.

In today’s environment, institutions again find themselves in a situation where their revenue is restricted, but this time it is because their prices have not kept pace with inflation. Federal COVID-19 stimulus funding provided to states and directly to students helped bridge the gap in the past couple of years, but those funds are no longer available.

Inflation’s impact on college costs may not be equally shared

That leaves revenue from students as a primary source of support to fill in gaps moving forward. But how much students pay differs by family finances. The public’s focus on the sticker price, the amount paid by higher-income families, makes it difficult to increase those much. Increasing costs by, say, 8% would be received very poorly. Several public institutions continue to freeze tuition in nominal dollars, which will amount to a significant drop in real revenue in a high-inflation environment.

These limits on the ability to increase tuition at a level large enough to keep pace with inflation will place higher education institutions in an even more difficult financial position. Of course, the handful with vast resources will work around this problem in the short term. Their finances are influenced by large endowments, making them less susceptible to these problems. Most institutions, though, will struggle.

What are the alternative approaches institutions can take to overcome the revenue shortfall? They certainly can reduce costs, scale back maintenance and renovations, and/or cut academic programs, for instance. Doing so, though, is difficult and perhaps even counterproductive. Those changes are also noticed and garner public criticism. It may also reduce their ability to attract students who pay full price.

To make ends meet, there is an easier alternative for them–cut financial aid. Public understanding of college costs after factoring in financial aid is so limited, nobody will notice. Despite its harmful effects, it is a much easier policy to adopt.

In fact, research supports the assertion that higher sticker prices and greater availability of financial aid go hand in hand. One study finds that public institutions provide more financial aid when they increase their sticker price (in real terms). They have greater resources available to do so. The opposite is likely to be true as well. When colleges are limited in their ability to raise sticker prices, they may resort to reducing the amount of financial aid available.

Beware of limiting access to higher education

All of this leads to the question of which students should be the focus in discussions of college costs. Traditionally, we highlight the price paid by higher-income students who pay the sticker price. That is the easiest number to know. And it would be better for these students if they could receive a quality education at a lower price.

But what about students from lower-income families? They are likely to be considerably more price sensitive. A higher price for them may mean the difference between attending college or not, the type of college that they attend, and the amount of debt they encounter if they do attend. Providing them with a price they can afford enables them to take advantage of the economic opportunity that a college education offers. The price they pay is the more important number to know, though it is obscured from public view.

In a high-inflation world, we risk missing the trees for the forest in our discussion of college pricing. It is unclear how long inflation will continue above traditional levels, but if it persists, it may limit college access. Restricting growth in sticker prices to maintain college affordability will benefit affluent students while possibly making college less affordable for those lower-income students for whom costs matter most. We should not lose sight of the goal of maintaining college access for those students as an integral component of the social mobility that we desire.

Commentary

Inflation affects the price of everything—including a college education

February 28, 2023