Teach For America (TFA), the staffing organization that selectively recruits recent college graduates and midcareer professionals to teach in high-need schools for a two-year commitment period, has shrunk by nearly two thirds from its peak just 10 years ago. TFA has long attracted its share of criticism for its operational model, with allegations that it reinforces disadvantaged students’ low access to qualified teachers and accelerates staff turnover in settings that need stability. On the other hand, the organization has also been praised for bringing individuals from elite backgrounds into the classroom, filling critical vacancies, and even initiating a new cadre of leaders in the nation’s education system.

In light of the pandemic and warnings of crises among the teacher workforce, how should we view TFA’s shrinking footprint? In this post, we update the evidence on TFA’s impact in public schools and situate the organization in the context of broader trends in the teacher workforce. We also include discussion of our own study of TFA in Miami-Dade County Public Schools. We argue that TFA has clearly had a positive impact on students and worry that its diminished stature creates space for less-rigorous and less-tested alternative certification programs to expand, possibly undermining teacher quality.

Reviewing TFA’s record

TFA’s history spans more than 30 years, famously born out of founder Wendy Kopp’s senior thesis at Princeton. From its founding cohort of nearly 500 corps members in 1990 to its peak at nearly 6,000 in 2013, the organization had only experienced meteoric growth. Since then, TFA’s retreat is hard to overlook.

These declines are happening despite the plethora of evidence documenting TFA’s efficacy. Multiple random assignment evaluations have been done on the program, showing TFA corps members are at least as good as—and in math, often better than—peer teachers in the same high-need schools. Several other studies have used rigorous empirical methods on administrative data across many different settings (and subjects). They all tell a similar story.

Our own study in Miami showed similar TFA performance advantages against peer teachers in the same schools in math and in English Language Arts, the latter of which is atypical in the TFA literature. TFA corps members also showed a modest improvement in other outcomes beyond test scores, such as students of TFA teachers being less likely to miss school from absences and suspensions. These improvements persisted one year after exposure to TFA, showing students may benefit in a variety of ways.

Principals in schools employing TFA corps members consistently report satisfaction at 80% or higher in recent waves of national surveys, including during the pandemic. Also, one survey found that 86% of these principals would hire another TFA corps member if they had a vacancy at their school. This squares with findings from our interviews of school administrators in Miami, where all expressed satisfaction and most would consider hiring TFA corps members again.

Some scholars have tried to open the black box of TFA’s operations to better understand what might be driving their performance advantage and concluded that it is primarily a story about the selection process. One examination found TFA’s highly selective screening process did a good job of selecting candidates prepared for both teaching in challenging settings and future leadership. Another found that much of the TFA advantage in math can be explained by measures such as college selectivity and teacher licensure scores. Another recent study found that a revamp of TFA’s selection process in 2005 created a stronger performance advantage among later cohorts.

Retention is still TFA’s Achilles Heel

The primary drawback to TFA is the limited two-year commitment. National estimates indicate just over half of TFA corps members leave their placement school once it’s fulfilled and about 15% remain in place at the five-year mark.

This low retention brings two disadvantages. First, teachers improve rapidly in the initial years of their careers, and the two-year commitment means that being in a TFA classroom is strongly associated with being exposed to a novice teacher. However, several different studies have found that the TFA advantage is large enough to offset the lack of experience, including ours in Miami, where post-commitment retention rates among corps members (around 25%) was significantly lower than national rates. Additionally, our analysis showed that corps members who stay beyond the two-year commitment were especially effective in their first two years.

Second, high turnover rates burden school administrators and students. Turnover imposes costs on schools both in the form of searching for replacements and in disrupted instruction, exacerbating inequalities. TFA’s retention rates are also lower than other teachers in high-poverty settings, though turnover in these settings is high even without TFA. New teachers also require support from school leaders and peer teachers, though TFA’s local offices provide considerable induction support to mitigate the burden on school personnel. Indeed, in our interviews, administrators did frequently cite low retention as the primary drawback of hiring TFA. However, this did not prevent these same administrators from reporting satisfaction with their overall TFA experience. Further, not all corps members leave after two years, with those who are older when they start being more likely to stay in schools long term, often eventually moving into school leadership roles.

Caution warranted for programs filling TFA’s void

Many principals have struggled to hire teachers in recent years, as schools have gone into overdrive to counter pandemic learning losses. Those in low-income schools have disproportionately experienced the most trouble filling vacancies–and especially in the STEM subjects in which TFA teachers appear to excel. The circumstances might be expected to represent a growth opportunity for TFA, but instead it is shrinking.

Why is that? Recent reporting on TFA points to recruiting challenges being the primary drag, with fewer candidates willing to undergo the selection process for a position in a relatively low-paying occupation in a high-need setting. Reports of stress and burnout during the pandemic have likely stymied interest, too. The article also notes TFA’s recruiting struggles are not unique, as other teacher residency and university-based alternative teacher preparation programs have faced similar drops in interest during recent years. Traditional university-based training programs have seen enrollment declines for more than a decade.

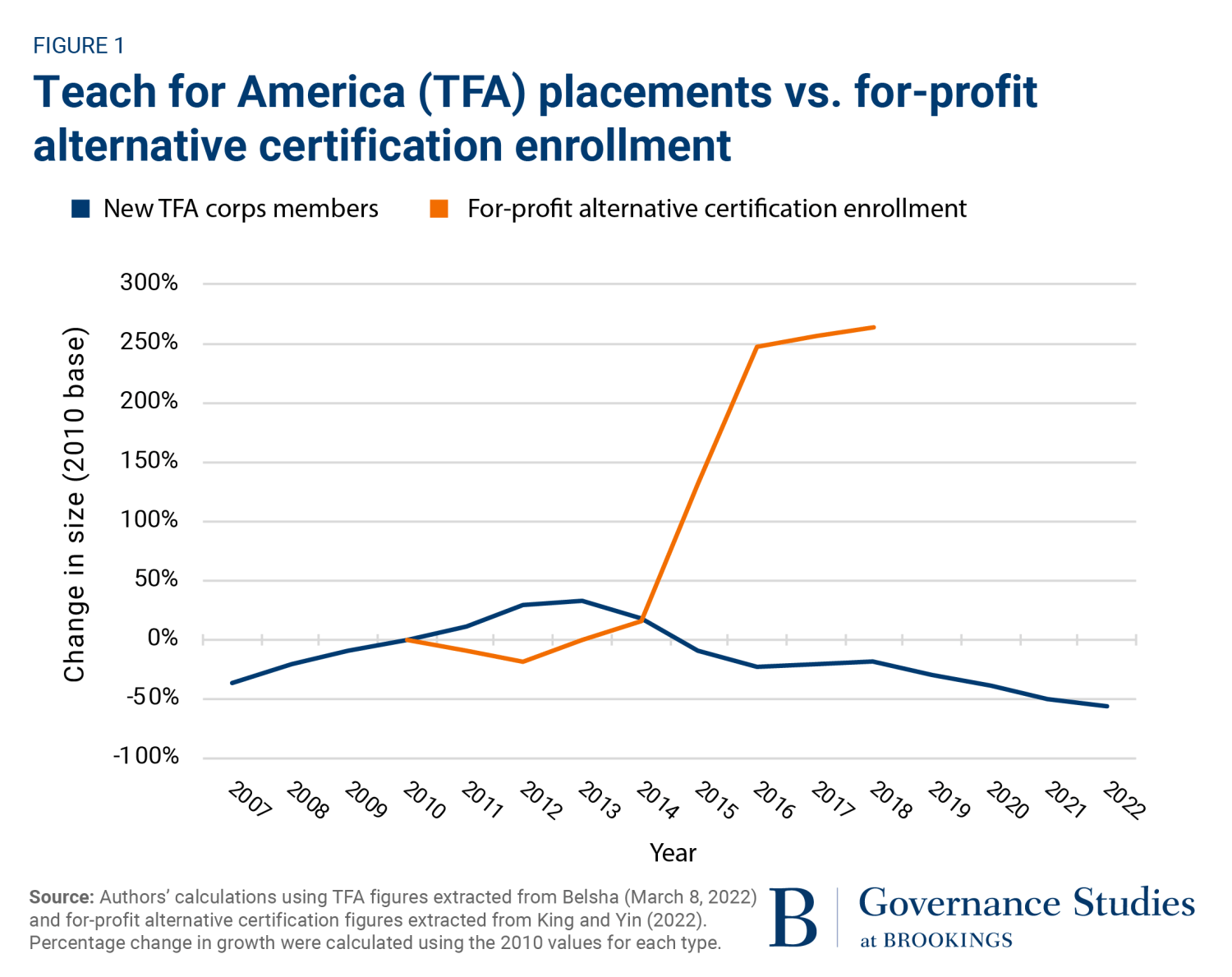

Who is filling the gap in teacher preparation if TFA and other legacy preparation programs are faltering? Often, a principal’s alternative to hiring from TFA is not a fully credentialed, traditionally trained teacher but rather one from a different (and much less selective) alternative route. Indeed, other alternative certification programs, especially for-profit programs, have been scaling to meet schools’ staffing demands, even as TFA has been shrinking (see figure 1). This is an important development, foreshadowing what may become a permanent shift in the workforce’s composition.

In contrast to TFA, however, many of these other programs are only minimally selective in their recruitment, and there is little evidence on how effective graduates are once they reach the classroom. For example, the rapidly expanding Teachers of Tomorrow program is the country’s largest for-profit alternative certification provider. Its growth accounts for most of the surge observed in Figure 1, and it has continued to expand in recent years (though the Title II data in Figure 1 do not extend beyond 2018 to provide exact figures). It is completely online and has received criticism for low program completion rates and academic rigor. We know of no evidence on how graduates of this program fare once they reach the classroom.

The experience of for-profit college students offers a cautionary, if imperfect, parallel to the rise of for-profit alternative certification. Leading up to and during the pandemic, for-profit college enrollments similarly surged even while more traditional institutions faced enrollment declines. These increases came despite the lower documented student outcomes for the sector, including lower graduation rates, lower employment outcomes, and higher student debt.

A warning sign that should prompt a policy response

Is the news of TFA’s diminished stature something that should be celebrated or dreaded? Many critics have long wished for TFA’s downfall, in favor of increasing professionalism among the teacher workforce. Though we, too, wish for a different teacher policy environment that would increase professional and financial rewards for those who lead our nation’s classrooms, we worry that TFA’s retreat may signal a turn for the worse as untested providers rush in.

Public perceptions of and young people’s interest in the teaching profession are near or at historic lows (spanning five decades). We suspect these new developments among alternative certification providers will only further these trends. Despite its drawbacks, TFA is an alternative certification model with an impressive record that we should be learning from, not shunning.

Commentary

Teach For America is shrinking—Is this cause for celebration?

January 31, 2023