The precise amount spent on teacher education is difficult to quantify, but one estimate suggests that the aggregate annual investment in the development of teacher candidates—i.e., an investment before individuals are even hired as teachers—is around $7 billion, or about $38,000 per teacher who enters the workforce. This figure, which is based on estimates of average college tuition costs, is quite significant. To put it in perspective, estimates suggest that annual per-teacher professional development costs are about $4,500, and teachers on average spend 14 years in the workforce, meaning that the investment in building teachers before they are hired is about half of the overall investment in professional development over the course of an average teacher’s career. Yet, until recently, most quantitative research on teacher development has focused on interventions targeting in-service teachers.

New data systems that connect the preservice experiences of teacher candidates with their in-service outcomes have expanded the evidence on how preservice experiences influence teacher effectiveness. This research has concentrated on whether a student teaching school’s student demographics, staff turnover and collaboration, and value-added estimates of school-level effectiveness predict student teachers’ subsequent outcomes. Although these school-level factors do appear to matter for future teacher performance, one student teaching placement practice appears to generate even larger returns: placing student teachers in classrooms with effective mentor teachers.

Several studies have now confirmed the importance of being assigned to a mentor who is highly effective (in value-added terms) with his or her own students. One of these is a study that we did in Washington state that followed more than 1,000 student teachers into the workforce, where we observed the later test performance of their students. We matched student teachers with their mentor teachers and identified the mentor teacher’s value added in the years before they supervised their student teacher (to avoid any confounding influence between the mentor and student teacher). It turns out that when former student teachers began teaching their own classes, their students performed better on standardized tests when their teachers had had a highly effective mentor teacher. Specifically, being assigned to a mentor that has value added that is two standard deviations above average (implying that the mentor raises the achievement of his or her own students by about 0.4 standard deviations more than the average teacher) is estimated to lead that teacher candidate to eventually, as a teacher, have students who do about 0.08 standard deviations better than average on standardized tests, all else equal.

Although this gain in performance may seem small, it is about the average difference in test score gains between students in a novice teacher’s classroom and students who have a third-year teacher. As we describe in more detail in a companion brief, this effect is larger than the effect of placing student teachers in highly effective schools or matching the classroom characteristics of the student teaching experience with those in student teachers’ first job. It is also larger than the perceived effect of a high congruence between the focal topics in a teacher preparation program and the skills needed on the job.

If being mentored by a highly effective teacher during student teaching is so productive, why doesn’t it happen more often? In the state of Washington, only 3% to 4% of teachers serve as mentors in an average year, which mirrors our best estimate of the percentage nationally (4%), given that there are about 3.2 million public school teachers in the United States and about 130,000 graduates of traditional teacher education programs (TEPs). Thus, at first blush, it seems straightforward that there is a significant scope for change in mentor assignments. Yet the limited quantitative evidence on this topic suggests that geographic proximity to a TEP and similarities between the mentor and student teacher are far stronger predictors of where and with whom student teaching occurs than mentor effectiveness. For example, a candidate is about five percentage points more likely to student teach with a mentor teacher who graduated from the same TEP than a mentor teacher from another TEP, whereas a very large increase in teacher effectiveness (two standard deviations) increases the probability of hosting a student teacher by less than a percentage point.

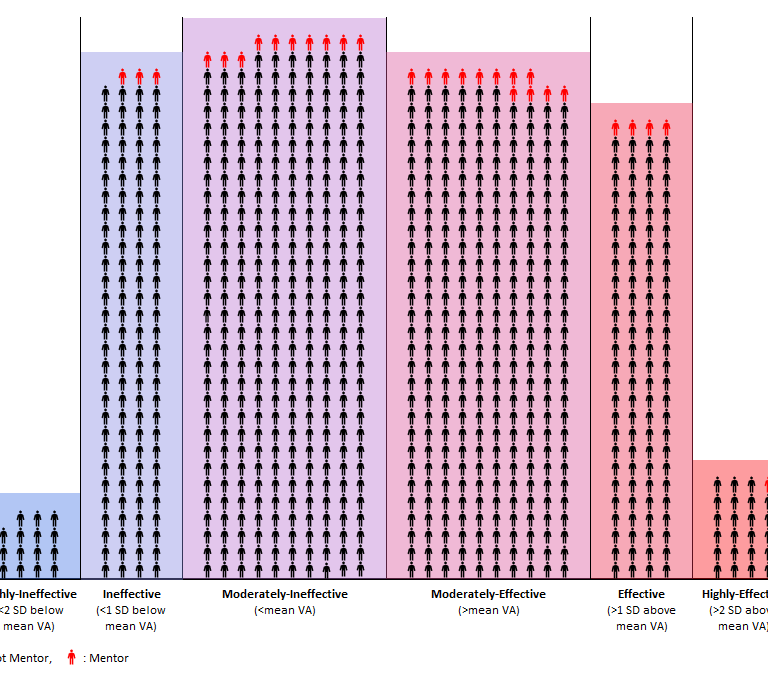

In some ways, these findings are not surprising because it is logistically challenging for TEPs to oversee internships that are more geographically dispersed. Thus, we are particularly interested in whether there are more effective teachers in schools and districts that already tend to host student teachers who might serve as mentors. To assess the potential for change regarding who serves as a mentor teacher, we use data on student teaching placements from 15 TEPs in Washington; this same dataset was used in the Washington state research discussed above. Based on these data, we created a figure that illustrates the availability of effective potential mentors relative to the number of teachers currently serving as mentors.

Each icon in this figure represents 10 math teachers in grades four through eight in Washington (grades in which value-added (VA) models of teacher effectiveness can be estimated) who teach within 50 miles of a teacher education program. We group these teachers into six categories based on their value added. Within each group, we highlight in red the number of teachers who serve as mentor teachers in a given year. Although more effective teachers are somewhat more likely than less effective teachers to host a student teacher, it is clear from this figure that a huge number of effective teachers are available to host student teachers. In fact, enough highly effective teachers are available to host all the student teachers currently hosted by teachers who are less effective than the average teacher in the state.

Although this evidence paints a rosy picture of the potential scope of change for student teacher placements, recent qualitative evidence from Washington suggests that there are also considerable challenges to changing the status quo placement processes. Interviews with individuals responsible for student teachers reveal skepticism that good teachers are also good mentors. Furthermore, some individuals appear to shy away from mentoring because they are uncomfortable with being differentiated from their colleagues. Perhaps most importantly, while mentor teachers may wish to give back to the profession by contributing to the development of teacher candidates, little financial incentive exists for teachers to serve as mentor teachers. For instance, one study estimated that an average mentor teacher receives only slightly more than $200 per student teacher.

This is much smaller than our back-of-the-envelope calculation of what effective mentor teachers are “worth” to students, schools, and districts. To calculate the value of effective mentors, we draw on evidence that having an effective teacher increases students’ long-term outcomes appreciably, including their labor market earnings. Now recall the result that the average teacher mentored by a highly effective teacher (two standard deviations above average value added) begins their career with the same effectiveness as the average third-year teacher in the state. This means that the present value to students of having a first-year teacher who student taught with a highly effective mentor teacher relative to an average mentor teacher is roughly $70,000 in lifetime earnings across an average classroom.

While this estimate of the value of more effective mentor teachers exceeds the range of reasonable compensation in the public education system, we can also draw inferences from how more experienced teachers are currently paid. In Washington state, we use publicly available salary data and calculate that the average full-time third-year teacher is paid $3,500 more than the average full-time first-year teacher. In other words, to the degree that the financial reward for teaching experience reflects the value that policy makers place on the increased value-added effectiveness of third-year teachers over novice teachers, policy makers ought to be willing to invest over 15 times more ($3,500 as opposed to $200) to encourage effective teachers to become mentors.

Teacher value-added effectiveness is only one dimension of teacher quality, and as noted above, being an effective teacher does not necessarily equate to being an effective mentor. With that said, evidence about the importance of mentor teachers for teacher candidate development is compelling, and the best evidence we can generate suggests substantial underinvestment in this crucial role. Consequently, we conclude by advocating greater focus on research into what constitutes effective teacher candidate mentorship and more policy attention (and potentially funding for teacher mentors) on how to ensure that teacher candidates receive high-quality mentorship during their student teaching.

Commentary

Leveraging the student-teaching experience to train tomorrow’s great teachers

May 20, 2019