If you have been anywhere near a university that trains doctoral students in the humanities, you will know that the market for new Ph.D.s is abysmal.

The plain fact is that we train far more humanities Ph.D.s than there are jobs for. In a recent year, the American History Association reported about 340 tenure-track job openings for historians, plus maybe another hundred jobs outside history departments that might recruit a historian. In the same year, American universities minted about 1,150 new Ph.D. historians. In economics, there were 2,650 new jobs and about 1,250 new Ph.D.s. The contrast is stark and largely typical of the situation in humanities versus STEM fields.

In part, this is not new. The “crisis” has been going on for an academic lifetime—at least since the 1970s. Academics who started their career when the Modern Language Association first reached the “melancholy conclusion” that, “should present trends continue, life … particularly in the humanities, could turn grim indeed,” well, those academics have now mostly retired.

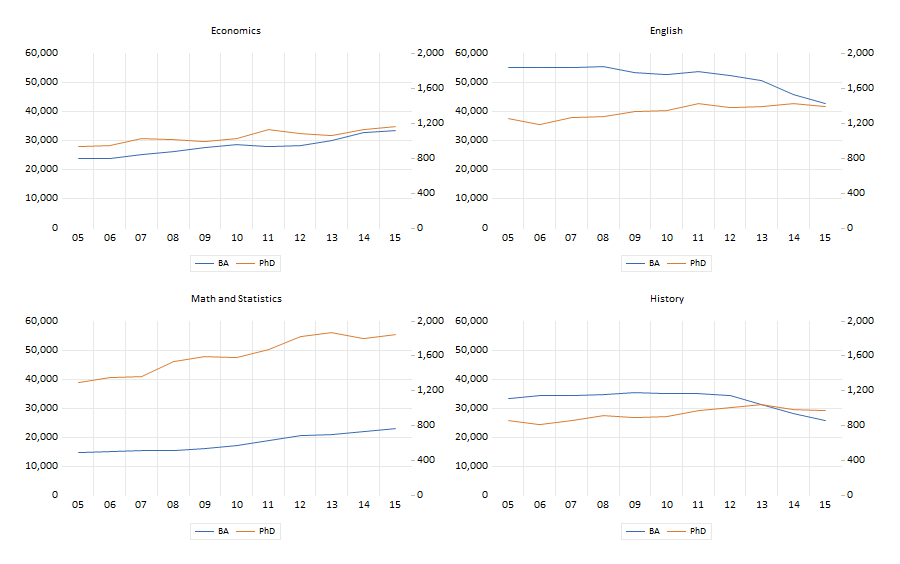

I want to talk about some possible reasons why more humanities Ph.D.s are produced than there are jobs for, especially in light of how long we’ve been in this dismal situation. First though, I want to raise a concern that conditions may be moving from dismal to disaster. Here are four graphs showing the most recent 10 years of data for the number of bachelor’s degrees (in blue) and the number of doctorates (in red) across economics, English, math and statistics, and history. The count of the former says a lot about the demand for the latter.

Figure 1: Comparison of B.A.s and Ph.D.s granted in economics, English, math and statistics, and history, 2005-2015

Look at economics and math/statistics on the left side of the figure. The number of bachelor’s degrees has grown, and the number of Ph.D.s has pretty much grown in parallel. Now look at English and history on the right. For the first half of the graph, the number of B.A. degrees was flat while the number of Ph.D.s grew rapidly. More recently, the number of bachelor’s granted in a year has plummeted while the number of doctorates has leveled off. One wants to be careful about extrapolating from five years, or even a decade. Nonetheless, things don’t look good. Why do the gaps matter? Because a big part of the demand for Ph.D.s in an area is to provide teaching for students pursuing their bachelor’s.

The economic problem in the humanities market is too much supply chasing too little demand. While one may lament the too-little demand, we’re left with the question of why supply hasn’t adjusted. Why do universities keep training so many humanities Ph.D.s when their market is so weak? It helps to understand that decisions about the number of Ph.D. students to admit are partially at the discretion of individual academic departments and partially decided by the choice of university administrators about how much money to allocate to a given department. It’s worth pointing out that resource allocations change very slowly in universities (but that’s slow on a scale of years, not slow on a scale of decades.) Let me suggest some reasons why universities continue to churn out so many Ph.D.s in the humanities.

Graduate students are cheap labor for teaching undergraduates, grading papers, etc. The suggestion is that it’s cheaper for universities to hire graduate students than to hire faculty.

Maybe, but I am less than enamored of this explanation because of the arrangements of salaries in research universities—which is where Ph.D.s are trained. Teaching assistant (TA) salaries are often set across the board, so they are the same in humanities and STEM disciplines. (More or less, as STEM fields are more likely to provide some supplements to TA pay. The “across-the-board” pattern is generally stronger in universities where the teaching assistants are unionized.) On the other hand, STEM faculty salaries are a lot higher than humanities faculty salaries. So if it’s a “cheap labor” argument, the excess supply should show up in STEM rather than in the humanities because the faculty/TA salary gap is larger there.

Graduate students are necessary for research and scholarship. Universities bring in humanities Ph.D.s to keep humanities faculty productive.

I suspect there is something to the need for graduate students to support research. And that makes it a valid reason, at least it makes it a valid reason for the university.

Graduate students may not be necessary, but humanities faculty really like to teach graduate courses. Humanities departments accept too many Ph.D. students in order to justify teaching graduate courses.

This is the explanation that I mostly believe, and this is also the explanation that I have no hard evidence for whatsoever. Just to be clear, economists also often like to teach graduate courses. I’m not suggesting any difference in attitudes or desires among humanities faculty versus STEM fields. The difference is that after coursework and after dissertations STEM Ph.D.s get jobs.

Faculty in the humanities see keeping a healthy graduate program as part of their mission to protect the role of the humanities in the wider world.

There’s no doubt about the importance of the humanities in helping us all do a better job of thinking through the problems faced in the world outside the ivy walls. I’m less sure whether producing an excess of Ph.D.s helps promote the value of the humanities in general.

Whatever the explanation of how universities benefit from producing more humanities Ph.D.s than the market will support, the question remains: Is it fair to the Ph.D. students? The Modern Language Association recommends “graduate programs routinely send applicants … data on the placement of recipients of PhDs from the department in the last three to five years (names of institutions, numbers of placements, fields of specialization).” Do humanities departments routinely make this sort of information available on the web? (Economics departments typically do.) I did some spot checking. Harvard does. Yale does. Michigan does. (My university, UC Santa Barbara, mostly does.) At three other major public universities I checked—nope. My suspicion is that humanities departments that place well despite the abysmal market are more upfront about placements than are departments with less enviable records.

Nothing I’ve said here will be new to anyone in the humanities. What’s more, the Modern Language Association, the American History Association, and others deserve credit for recognizing the situation and doing what they can about it for decades now. The problem does not lie in particular universities; the problem is that each university’s reasonable behavior adds up nationally to more humanities Ph.D.s than there are jobs for. Everyone wants some other university to shrink production.

One more thing. Humanities Ph.D.s do find jobs. After all, one has to be very smart to get into a Ph.D. program, and very persistent and talented to earn the degree. Unfortunately, while humanities Ph.D.s can find jobs outside academia, the financial reward isn’t much at all considering the 6 to 10 years the Ph.D. takes. The National Science Foundation reports that the average annual salary for new humanities and arts Ph.D.s who do have a job is about $52,000 a year. A comparable salary number for people with a bachelor’s in any field, aged 30 to 35 with full-time employment, is about $61,000. It’s a depressing state of the world.

Commentary

How many humanities Ph.D.s should universities produce?

October 24, 2018