Jeanne Wallace is a political liberal in a blue state who regularly talks with her high school social studies class about economic inequality. Well aware of the growing nationwide gap between society’s haves and have-nots, she wants to teach her students a range of causes, consequences, and possible solutions for economic inequality. “I’m conscious of the fact that they may never go on to take a political science class,” Wallace told us referring to her 12th-grade government students. Her class could be the only time they’re exposed to these issues, she said, “and then we dump them into the world and let them vote.”

Across the country, Fred Franklin describes himself as a political conservative living in a red state. He teaches “European History” and “U.S. Government” to students from middle-income families in a town that is still reeling from the closure of a major auto plant during the Great Recession. Franklin frequently talks with his students about economic inequality as they learn about the industrial revolution and late 19th-century labor unrest. He likes to draw connections between historical debates about wages and working conditions, and contemporary issues facing the community where his school is located.

Given public schools’ generally allergic reaction to all things controversial, it is tempting to assume that Wallace and Franklin are exceptional cases. But, our first-of-its-kind national study suggests that many other social studies teachers are also talking with their students about economic inequality.

This finding comes from a nationally representative survey we conducted of 685 public high school social studies teachers in 293 schools, as well as follow-up interviews. The survey asked teachers about whether and how often they talk about economic inequality with their students. It also explored what topics they cover when they teach about economic inequality as well as how and why they address these issues.

Almost all teachers we surveyed reported that they taught about economic inequality during the school year, with more than half saying that they did so at least weekly (see Figure 1). To our surprise, liberal teachers (like Jeanne Wallace) in blue states are no more likely to teach about economic inequality than conservative teachers (like Fred Franklin) in red states. In fact, a teacher’s ideology does not predict the frequency with which she teaches lessons about inequality at all. While liberal teachers are more likely than conservative teachers to report that economic inequality is a topic of particular concern to them personally, both liberal and conservative teachers more or less equally believe it should be part of the curriculum and classroom discussion. And they talk about an array of issues—from taxes to trade to social welfare—with similar frequency.

Only on issues that directly invoke ideological scripts do we see differences in the topics that liberal and conservative teachers address when they teach lessons about economic inequality. Liberals talk more about systemic injustices, racial discrimination, and gender equality while conservatives talk more about financial literacy. The former provokes discussions about structural issues of fairness while the latter emphasizes self-reliance and personal responsibility.

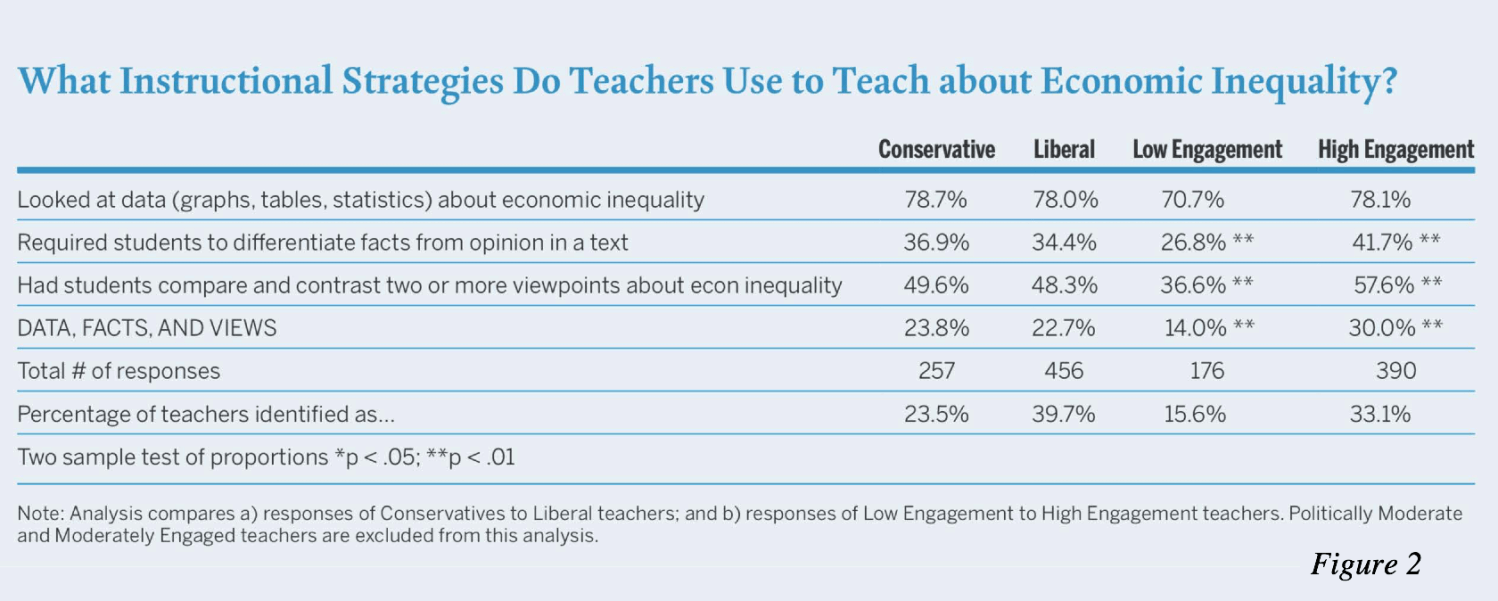

And when addressing issues of economic inequality, liberal and conservative social studies teachers are equally likely to require their students to look at data, differentiate facts from opinion, and compare and contrast different viewpoints. Yet, as we show in Figure 2, highly politically and civically engaged teachers are more than twice as likely as their less engaged peers to use all these sophisticated instructional strategies with their students.

If a teacher’s ideology doesn’t correlate with how often they teach about economic inequality, what does? It turns out that a teachers’ level of civic and political engagement (whether they follow the news, are engaged in community groups, are generally aware of political debates), but not their political ideology, predicts whether and how often they teach about economic inequality. Conservative teachers, for example, are just as likely as liberal or moderate teachers to teach about the topic regularly.

It is likely that the knowledge and experience teachers gain from their own political and civic engagement makes them more comfortable with and committed to the idea of engaging their students with these issues. More politically engaged teachers would also likely have greater exposure to civic deliberation and the ways evidence is or is not used to bolster such arguments.

This is not to say that all politically engaged teachers expose students to multiple perspectives, evidence, and argument, but rather that they are quite a bit more likely to do so than their non-engaged peers.

In these highly charged political times, it is striking that teaching about inequality is not driven by ideology, but rather by the degree to which teachers are politically engaged outside of the classroom. This underscores the importance of creating work environments where teachers are free to engage civically and politically without fear of sanctions or reprisals. Teacher education programs and school districts alike should seek to nourish teachers’ civic identities, not hinder them. This means encouraging new and experienced teachers to follow the news, engage in civil discourse with one another about topics of public concern, foster ties to community-based organizations, and participate broadly in civic life.

The idea that schools should be “above politics” has historically served to curb political discussions in classrooms. If we are to educate thoughtful, civically engaged students, we must reclaim the important place in the classroom for the discussion of difficult political issues. Governments that are of the people, by the people, and for the people, require the people to have some knowledge and familiarity with not only democratic institutions but also contemporary issues and debates. Yes, classrooms should be political, but not in the way we so often fear. Being political means embracing the kind of controversy and ideological sparring that is the engine of democracy and gives education its meaning.

Commentary

Teaching about economic inequality is political, but not the way you think

December 6, 2017