America is engaged in an active discussion about reducing the flow of immigration. Perhaps surprisingly, immigration matters a lot for the supply of K-12 teachers. About 8 percent of American teachers were born abroad. If the supply of teachers were to be reduced by 8 percent, schools would be in deep trouble.

Some care is needed in this discussion. There are two different discussions ongoing with regard to immigration: undocumented people and people here legally. There are some teachers who are undocumented, but I suspect there are not many. In comparison, there are presumably many more teachers who immigrated to this country legally. There are also teachers here on temporary work visas, but again, I suspect not many. We are likely talking about a long-run issue, in which the supply of immigrant teachers and immigrants who might become teachers in the future teachers would be cut off, reducing the (already stretched) K-12 teacher pool.

What are the facts? The figure below gives the fraction of primary and secondary school teachers born outside the United States using data taken from IPUMS USA, composed of various years of the U.S. Census and the American Community Survey by the University of Minnesota. In 1950, shortly after the end of World War II, about 4 percent of teachers were foreign born. The fraction dropped to 2 percent by 1960. Since then, the foreign-born fraction has increased steadily, having just topped 8 percent in the most recent data. The fraction of foreign-born teachers is lower than the fraction of immigrants in the general population. However, the teacher fraction is only a little lower than the fraction of legal immigrants in the general population. In this sense, the number of foreign-born teachers is in rough proportion to the foreign-born population.

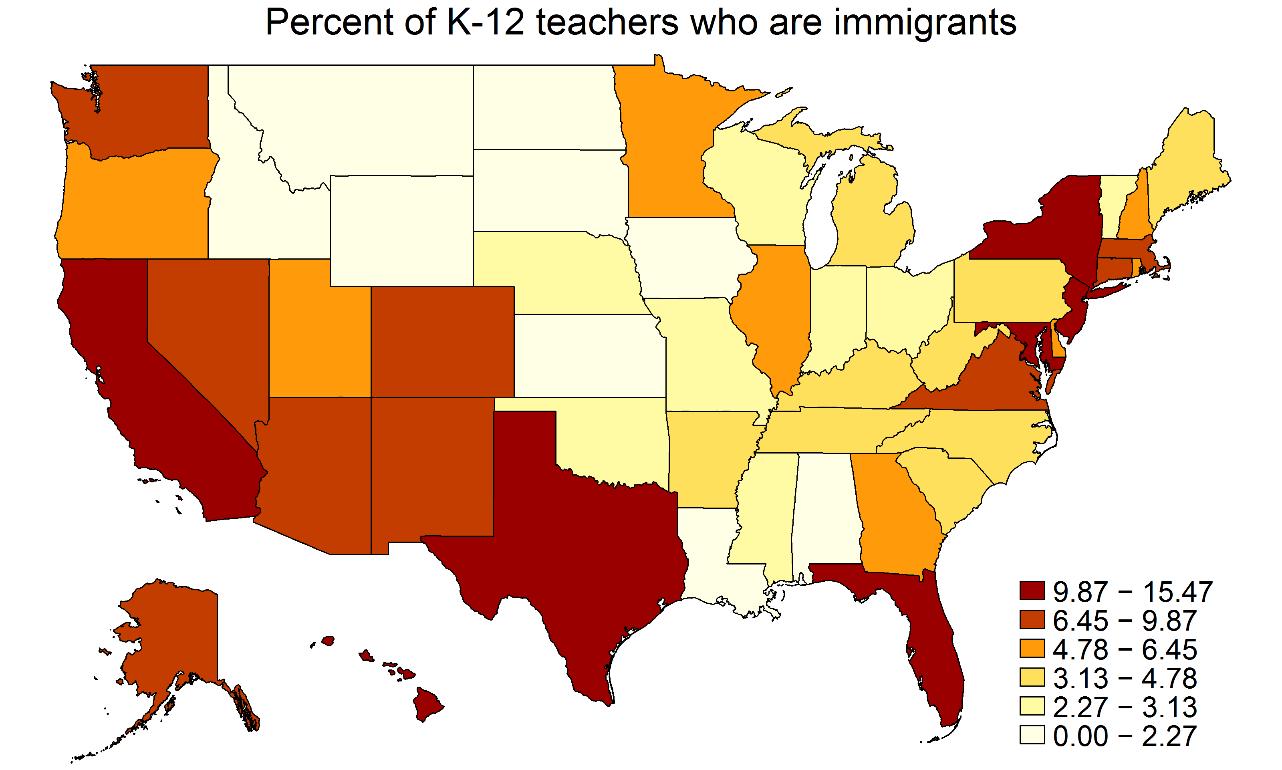

Immigrant teachers are not spread evenly across the United States. If we didn’t have teachers from abroad, Alabama and Vermont would be not much affected. On the other hand, California and Florida would have teacher supply disasters if there were no foreign-born teachers. The next picture shows the distribution of foreign-born teachers across the U.S.

To a considerable extent, there are high numbers of foreign-born teachers in states that have high numbers of foreign-born residents. (Interestingly, Alaska has an unusually high number of foreign-born teachers relative to its overall immigrant population.)

If you were to guess where foreign-born teachers migrated from, you would probably guess right. The largest single “donor country” is Mexico, followed by China. The next figure shows the major homelands of teacher immigrants to the U.S.

It isn’t surprising that many teachers are from China, since it has the world’s largest population. It might be surprising that so many teachers are from the lightly populated West Indies, although of course many of the islands have strong historical ties to the U.S.

The quick summary is that teachers who have migrated to the U.S. are a vital source of teachers. That’s especially true in the parts of the country that have a large immigrant population. None of the proposed changes to immigration policy is likely to cause any short-run crises because few of the changes would affect legal immigrants who are already teachers. (The future for undocumented teachers is much less clear.) But if we were to severely restrict immigration as some have proposed, we might be facing a critical teacher shortage a few years down the road.

Commentary

Immigrant teachers play a critical role in American schools

March 16, 2017