The last election made clear that Americans want to improve our balance of trade in order to protect jobs. Something not often realized is that education—particularly higher education—is a major American export. If new border controls prevent the entry of foreign students, or simply makes them feel unwelcome so they go elsewhere, American jobs and American students pay the price.

If you are not an economist, the idea that America’s education of foreign students is an export may seem strange. What makes a service like education an export is that foreigners pay U.S. institutions, so money flows into the U.S. from abroad. Education of a French student in the United States is an export in exactly the same way that the visit of a Chinese tourist to Disneyland is an export, or the provision of stock brokering services on the New York Stock Exchange to a German financial company is an export. When we provide a service that leads to foreigners sending money into the U.S., that’s an export with exactly the same economic effects as when we sell soybeans or coal abroad.

The value of education exports is not a small number. According to the government’s Bureau of Economic Analysis, education accounts for 5 percent of the entire national export sector. (Most of the education spending is presumably in higher ed.) I will explain in a moment why this is an underestimate. First, here’s a picture of the official value of exports and imports in education.

Exports in education topped $35 billion in 2015. Not only is the blue (export) line much higher than the green (import) line, the gap in our favor is growing rapidly. By the way, this is one of the few sectors where the trade gap is in America’s favor.

As I wrote above, there is good reason to believe that the official numbers understate the importance of education exports. The numbers reported measure direct spending on education—tuition and the like. They do not include spending on room and board, used cars, pizza shops, or anything else college students spend their money on. Research by John Douglass, Richard Edelstein and Cecile Hoareau from 2011, “US Higher Education as an Export,” reports that the estimated economic impact of higher education, taking out financial aid and adding in cost-of-living expenses, raises the direct economic impact by 43 percent. (The extra 43 percent measures direct spending only, excluding indirect effects of job creation and the like.) Unless that ratio of extract spending has changed, the total value of education exports today tops $50 billion.

There is a good argument to be made that higher education is one of our most successful export sectors. We’re good at higher education, and the rest of the world flocks to our shores and pays for the chance to study in America. Just under 5 percent of college students in the United States are visiting from abroad. As argued above, this is critical for exports. It’s economically critical for something else: Foreigners subsidize American students. Foreign students are generally eligible for very little foreign aid. They pay full freight. Especially in public universities, such as the one at which I teach, those dollars are critical in replacing the money that used to be allocated by state legislatures.

Blockading our borders risks driving away students and their dollars in two ways. The first is straightforward: Effectively excluding students from Muslim countries would mean we lose a lot of customers. The United States had 60,000 Saudi Arabian students in 2014-15. While well below the number from China and Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia was the fourth-largest source of foreign students, just edged out for third by South Korea. Other predominantly Muslim countries also send us a considerable number of students. Taken together, Indonesia, Turkey, Iran, Kuwait, and Pakistan send roughly another 45,000 students.

The second way that building barriers hurts us is by making students from all countries feel unwelcome. Ignoring the issue of building goodwill toward the United States, the fact is that universities around the world would love to out-market us. Universities in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia teach in English and already have a higher ratio of foreign to domestic students than does the United States. (New Zealand and Ireland also have higher ratios than we do, but as exporting countries are too small to be major competitors.) In addition, many universities in Europe have switched part or all of their instruction to English to be more customer-friendly to foreign students.

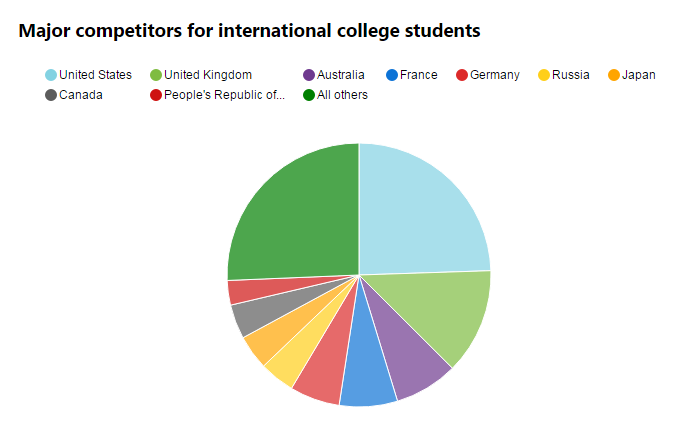

Right now, the United States is the leading supplier of slots for international students, with about a fourth of the world market. You can see in the following chart that the U.K. and Australia combined trail us only by a little bit. This is a market we lead, but it is also a market we could lose.

Education as an economic export is likely not the first concern about how we operate at the border. Still, blocking American exports and moving the associated jobs overseas doesn’t seem in step with our national goals.

Commentary

Sealing the border could block one of America’s crucial exports: Education

January 31, 2017