What changes for students and teachers if we see learning environments as games? At the University of Michigan, where a community of practice around “gameful pedagogy” is emerging, we have some evidence of interesting benefits. Learners can become more willing to explore new areas and approaches, develop a greater awareness of themselves as learners, and thereby achieve a greater agency over their education. Teachers can become more conscious of their learning goals and how to achieve them.

And we may realize that school was a game all along—just not a very good one, as my colleague and collaborator Barry Fishman likes to quip.

What does it mean to call learning environments games? Students often enter our classrooms as if stepping into a new, virtual game-world—a setting that is somewhat bewildering, with some recognizable practices and purposes, but also with confusing and apparently random rules you’d better figure out before you get blown up (or more likely just flunk). Why do we need to read Plato? Where can I use linear algebra? What is this discipline called “complex systems”? And why does one instructor ban laptops in the classroom when another professor requires them? How do I get an A?

What’s so bad about the conventional school game, then? Its “quests” tend to have high stakes, which discourages risk-taking and exploration. Conventional learning environments are also quite linear. That is, paths from the beginning to end are direct and inflexible, with most students expected to do the same things: “There are three midterms and a cumulative final,” or “Write two five-page papers and one ten-pager.” When applied to video games, “linear” is usually a devastating critique.

Gamers don’t like “linear” because it undermines an essential feature of games: the sense of exploration and discovery. To get to explore is to develop one’s agency, to be responsible for one’s choices. Good games do this by encouraging exploration.

The explicit treatment of non-game practices as games is often called “gamification.” At the University of Michigan, we have begun to call our approach “gameful,” to highlight subtle but important differences. For us, learning through games is less about what you call things—turning “assignments” into “quests” or “grades” into “leveling up”—than about the underlying logic of what we do.

In my own courses, gameful means three related things. First, there are multiple paths to achievement: Students can learn the material in many different ways, practice different kinds of academic work, and demonstrate their learning through different means. For example, a student might prefer to write publicly accessible blog posts about what she has learned about John Stuart Mill, while another might prefer a conventional academic essay on the same topic. Or a pair of students might best understand Niccolo Machiavelli’s political theory by writing songs about it because they are musicians, and connecting something they like and know to the new and difficult makes it more interesting and meaningful. Multiple paths acknowledge the different skills, interests, and backgrounds of the students in our courses.

Second, whatever you do, you learn—and earn—something. Students begin the semester with a zero and gain points as they complete assignments. The purpose is to motivate students and to signal that all practice involves some learning. When you score 95 on a conventional 100-point assignment, you did well, but somehow you “lost” points. When assignments are framed as adding to your stock of points, however, even the assignment on which you didn’t do as well as you had hoped earned you something you didn’t have before, and demonstrated you had learned something you didn’t know before.

And, third, this means that instead of constant high-stakes assessment, the approach allows for safe failures. Arguably better than educators, game designers have figured out how to build “desirable difficulties,” challenges that motivate us to try again even if we first fail. One of their key ideas is that failures aren’t high stakes—you can’t really die in a video game. Similarly, we believe students shouldn’t risk ruining their GPAs with one or two assignments, either.

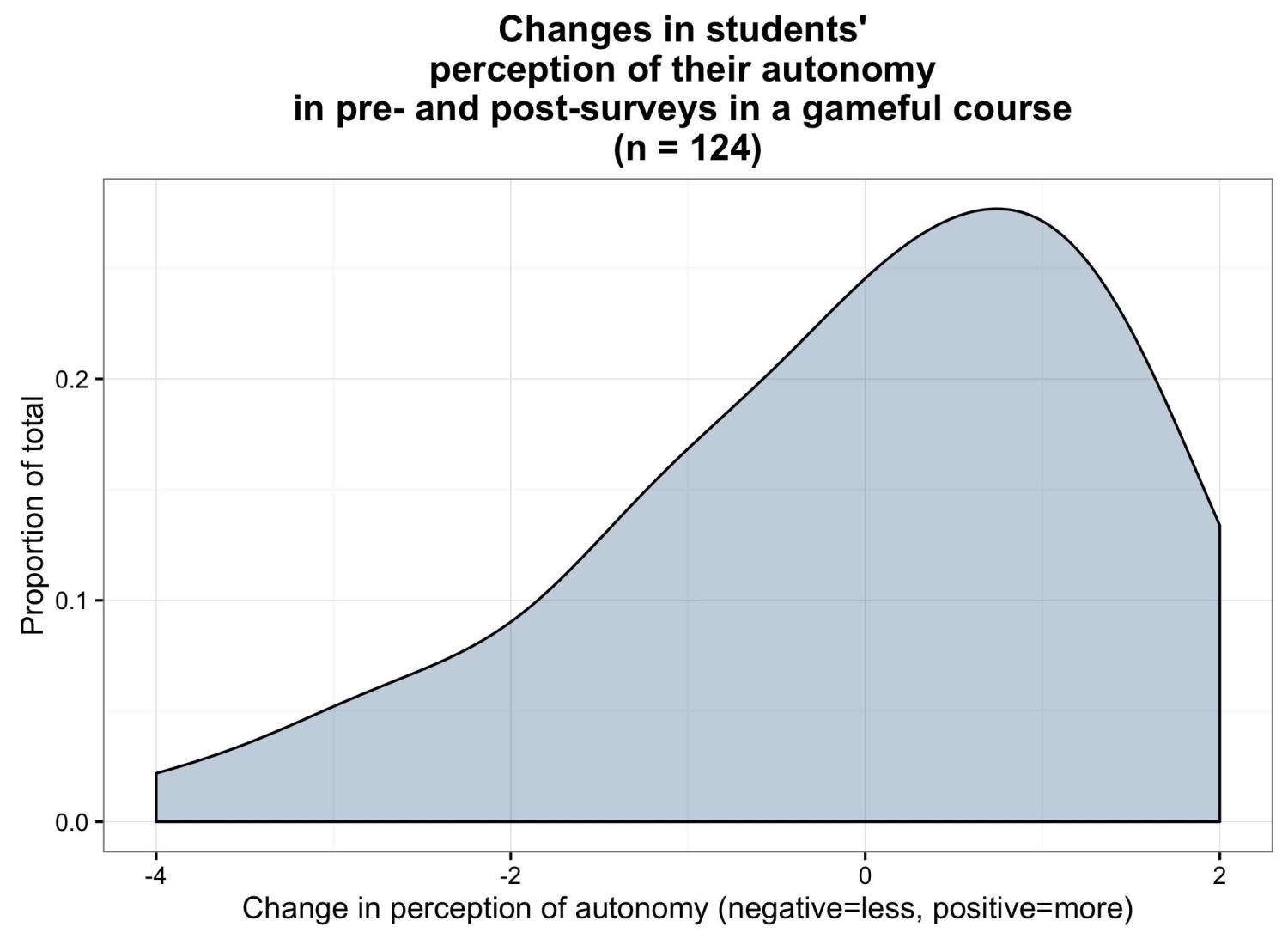

Does this approach work? It depends on what our goals are. For me, fostering student autonomy is as important as subject mastery. Autonomy is not the same as freedom; it involves, importantly, an individual’s awareness of herself as having both choices and responsibility. The evidence we have collected from gameful courses suggests more students feel a greater sense of autonomy at the end of a gameful course than they did at the beginning.

Below is evidence from one medium-sized gameful course (a 160-student course aimed at first-year students). In surveys at the beginning and end of the semester, we asked a set of questions about the students’ own perception of their autonomy. The curve shows what proportion of students felt their autonomy increased (a positive number) or decreased (negative) during the course. The majority of the students saw an increase, although it is important to note that some students also felt their autonomy decreased. (The positive increases end sharply at two because the initial responses tended to be at the high end of the seven-point scale.) The overall change is modest, but we see the positive direction replicated in other gameful courses.

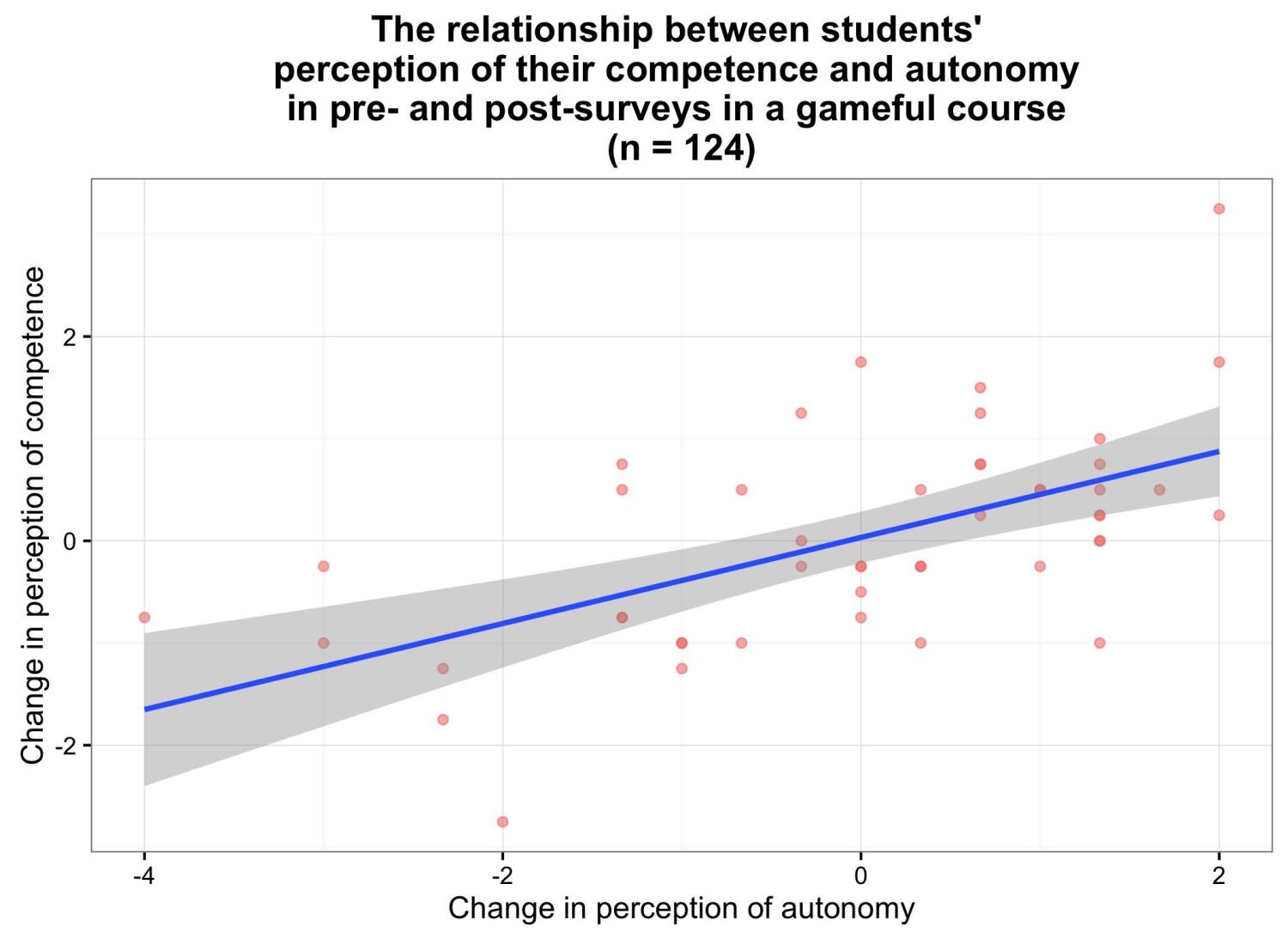

What about mastery? Grades are the familiar, however problematic, way of measuring competence, but because gameful approaches affect grading schemes, we cannot use grades or grade distributions in gameful courses as evidence of greater mastery, even though they are generally higher. (Students tend to do more work.) But consider the chart below. It suggests that my learning goal, student autonomy, correlates with students’ perception of increased competence.

Sure, students’ own perception of their own competence is not the same as competence. Indeed, it might be a feature of the Dunning-Kruger Effect or at least what education scholars call the illusion of understanding (you think you get it, but maybe you don’t). But even if that is what’s going on, a student who feels competent and autonomous will feel empowered to take on more challenges. Previously undesirable difficulties can become desirable.

Should student autonomy be a learning goal? At a time when mere information provision is a losing proposition for pedagogy, I believe it should. To revisit my earlier comment, school has always been a game—just one we as educators haven’t done very well. Applying gaming principles to the classroom could have a big payoff. By simply redesigning the learning environment in a few subtle ways, we may be able to stimulate student engagement for seemingly effortless learning. And based on the early results of what we’re seeing in our work at the University of Michigan, the classrooms of the future will look distinctly more game-like than they do now.

Commentary

From ‘Skyrim’ to school: How game principles can improve student learning

January 27, 2017