Personalized learning practices are increasingly being used in a variety of K-12 settings. These include public, private, and charter schools; at elementary, middle, and high school levels; in many content areas—including core subjects like reading, English language arts, math, and writing; and with students from various backgrounds. The current pace of growth in the implementation of personalized learning means that questions about its effectiveness are becoming relevant to an increasing number of classrooms, educators, students, and families across the nation.

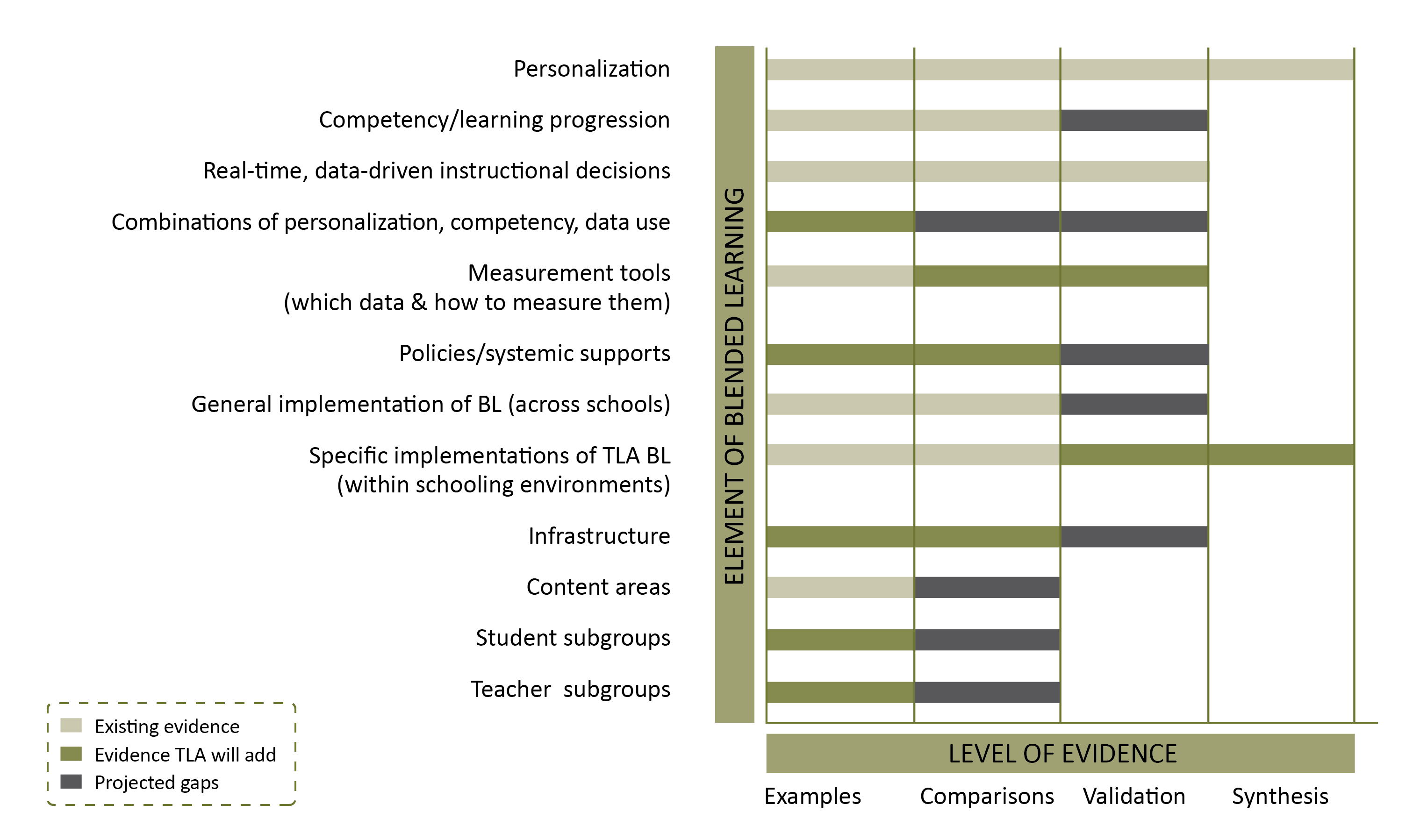

Last month, The Learning Accelerator (TLA) released our Measurement Agenda for Blended Learning, a resource that outlines the skills, knowledge, and activities necessary for researchers, educators, administrators, policymakers, funders, and others in the community to build our evidence base and advance our collective understanding of blended learning’s effectiveness. This resource begins by outlining the current state of evidence in the field and describes the challenge we face in contributing to this evidence. The current state of evidence is summarized in the resource by the following chart (pg. 9):

Levels of Evidence for Core Elements of Blended Learning

The chart summarizes the strength of existing research evidence of 12 core elements of blended learning, from structural elements like personalization, competency, and use of data; to contextual elements like infrastructure, content areas, and student and teacher subgroups. As you can see, there are varying levels of evidence across the core elements, with (generally) the highest levels for structural elements and the lowest, if any at all, for contextual elements. We expect these gaps in evidence for contextual elements of blended learning to persist into the foreseeable future.

We consider personalization to be a core element of blended learning, and a common reaction to this chart focuses on the level of existing evidence documented for personalization. Are we really “finished” with studying personalization? Can we say we have enough evidence that personalization is best for students, and move on? Not exactly, and here’s why: there are a few contextualizing factors for this chart overall that will help with interpretation.

First, the chart outlines evidence of effectiveness – not necessarily effective implementation. For all of the included elements of blended learning, the levels of existing evidence, evidence TLA expects to add, and the projected gaps focus on whether or not the element itself is causally linked to improved student outcomes. (Outcomes here include academic and nonacademic outcomes.) Therefore, there is still more to learn about the contexts in which and constituents for whom personalization is more or less successfully implemented—and we still need to gather evidence about those.

Next, we define personalization as a group of practices that ensures each learner’s instructional need is met—in other words, instructional practices that include differentiation or individualization of content, difficulty, and mode of instruction, among other things. In this chart, “personalization” means that modeling, scaffolding, guided, and independent practice occur as necessary at the level of each individual student’s need.

Finally, we used several sources to determine what level of evidence exists for personalization. In fact, there are numerous studies that focus on the individual practices that make up personalization, so many that meta-analyses and syntheses, and even meta-meta-analyses, exist, all showing moderate to large effect sizes for these practices. This body of work, and specifically these syntheses, are outlined in our earlier resource, TLA’s Blended Learning Research Clearinghouse (refer to table 1 of the report for further info). Some of the practices include:

- reducing group size,

- using formative assessments to inform instruction,

- providing opportunities and time for guided and independent practice,

- facilitating self-regulated and intrinsically-motivated learning, and

- deploying scaffolded instruction to facilitate mastery, among many others.

As should now be apparent, we do have a very solid base of evidence showing the effectiveness of the instructional practices that enable personalization. Yet, it is not the case that we know everything we need to know about implementing personalized learning in such a way that all learners are supported and teaching and learning improves. For example, we do not know if there are particular students, or teachers, for whom implementing these practices are more or less successful. We also do not know if there are certain content areas in which personalizing is more or less effective. The field would benefit from more evidence about whether certain combinations of personalization practices are more effective than others, or if specific infrastructural supports foster or hinder the successful implementation of these practices.

Let us build on that base of knowledge to improve our understanding of how to best implement personalization—an effective means of supporting all learners.

Commentary

Personalized learning: Trendy and true

June 8, 2016