There is a growing interest in proposals to make college affordable for students without requiring that they take on large amounts of debt. To this end, two of the Democratic candidates for president have put forth plans to improve college affordability which include having students work while enrolled. O’Malley has proposed expanding the Federal Work-Study Program and making work-study jobs more career-focused. Clinton’s college affordability plan calls for students to work 10 hours a week. Finally, the Lumina Foundation’s Affordability Benchmark for Higher Education, which was released at the end of the summer and discussed during a recent convening , also calls for students to work the equivalent of 10 hours per week while enrolled in college.

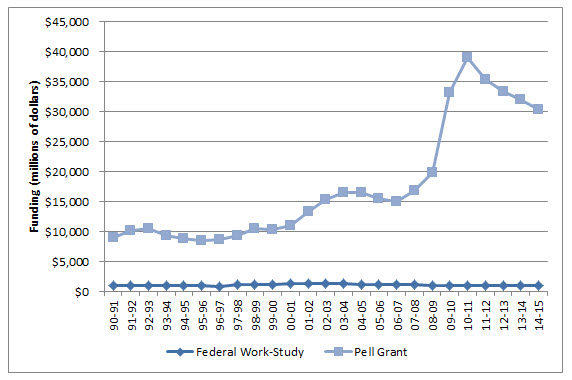

The idea of having students partially finance their college educations by working during the school year is not new. The Federal government has been subsidizing college student wages through the Federal Work-Study Program since 1964, though funding for this program has remained stagnant for years. Figure 1 compares trends in funding for the Federal Work-Study Program to funding for the Pell Grant. Moreover, according to recent data from the American Community Survey, 72 percent of college students already work at least part-time. Though the work-study program has been part of the financial aid landscape for decades and the majority of college students work, we know very little about how working while enrolled affects college students’ academic outcomes.

Figure 1: Trends in funding for Pell Grants and the Federal Work-Study Program

Data source: College Board

Note: Funding amounts are in constant 2014 dollars.

Though it is important to understand college student employment more broadly, the impact of participating in the Federal Work-Study Program is particularly policy relevant, because we can induce students into or away from these jobs by increasing or decreasing funding for the program. Importantly, research on the impact of holding a work-study job may provide a lower bound on the estimated impact of working while enrolled. The majority of these jobs are on-campus, which may be better for students if they are able to schedule these jobs around academic commitments and avoid wasting time traveling to off-campus work.

A handful of studies suggest that holding a work-study job has only minimal negative effects on students’ academic outcomes. Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner find a small, negative impact of working on the GPAs of students at a single institution in Kentucky.[1] Judith Scott-Clayton, in a paper that makes use of data from West Virginia, finds that holding a work-study job has a small, negative effect on academic outcomes for women.[2] I and my coauthor, Bridget Terry Long, add to the evidence on how working while enrolled impacts academic outcomes for college students using a large sample of students from the Ohio public university system. We find that participating in the Federal Work-Study Program has a small, negative effect on students’ first-year GPAs.[3] Finally, a recent paper by Judith Scott-Clayton and Veronica Minaya makes use of a national sample and finds that holding a work-study job has small negative effects on academic outcomes for students who would not have worked in the absence of the program. However, these authors find that for students who would have worked even without the work-study program, participating in the Federal Work-Study Program has positive effects on academic outcomes.[4]

Though this research contributes to our understanding of how working while enrolled affects college students, several important questions remain. For example, does working affect students’ academic outcomes because it takes away from the time students spend studying? Also, does working have unintended consequences, such as influencing which majors students choose? In addition, there are potentially positive impacts of working that haven’t yet been explored. For example, working might lead some students to develop better time management skills. Students who work during college may also learn more about how to interact with an employer than those who don’t, and this may help them when they enter the labor market after graduation.

For some students, working a reasonable number of hours while enrolled in college may be a viable way to contribute to college costs. However, before we finalize college affordability plans that require students to work during the school year, much more research is needed to better understand how to design these plans so that working is not detrimental to students’ progress.

[1] Stinebrickner, T. & Stinebrickner, R. (2003). Working During School and Academic Performance. Journal of Labor Economics 21(2): 473-491.

[2]Scott-Clayton, J. (2011). The Causal Effect of Federal Work-Study Participation: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from West Virginia. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33(4): 506-527.

[3] Soliz, A. and Long, B.T. (2015). Does Working Help or Hurt College Students? The Effects of Federal Work-Study Participation on Student Outcomes. Harvard University, unpublished manuscript.

[4] Scott-Clayton, J. and Minaya, V. (2015). Should Student Employment be Subsidized? Conditional Counterfactuals and the Outcomes of Work-Study Participation. Economics of Education Review, in press.

Commentary

Should college students be required to work to finance their educations?

December 21, 2015