A possible teacher shortage has been much in the news—in California, for instance, the number of new credentials has fallen by about half since 2004, while K-12 enrollment stayed roughly flat. (Take a look at Paul Bruno’s July Chalkboard.) Whether this is a transient, post-Great Recession blip, or if it’s a major trend is not yet clear. It’s hard to say just yet what fewer teacher candidates means for teacher quality, because we don’t know much about how the characteristics of people getting certified has changed, or whether or not schools are having more trouble finding good candidates. However, I’d argue that the drop-off in credentials actually creates an opportunity to raise teacher quality through another channel: improvements in student teaching.

A chance to trade off lower quantity for higher quality

As I discuss below, evidence suggests that a high-quality student teaching experience is valuable in getting a new teacher off to the right start. But people who’ve looked at the question tell me that practice teaching is currently over-subscribed and under-managed—there aren’t enough high-quality slots available, and as I describe below, standards are low. The current drop in the number of new teaching credentials, at least some of which have historically gone to people who never end up teaching, makes it more likely that new teachers will get the chance to learn from a top-notch mentor.

In short: Fewer teacher candidates vying for limited student teaching slots could mean better prepared newbie teachers. If education programs take the opportunity to shore up their requirements, the teacher “shortage” could in part translate into a tradeoff of smaller quantity for higher quality.

Student teaching: Exploring the data (and the lack thereof)

A first question might be “Is a high-quality student teacher experience important?” Very little data exists on student teaching experiences and outcomes. But, the available scientific evidence on the topic suggests that the answer is yes.

Donald Boyd and colleagues looked at teachers in New York City schools. They found that oversight of student teaching assignments by a teacher candidate’s program led to notably better outcomes (measured by value-added scores) in the first year of teaching. “Oversight” here meant that the cooperating teacher had a minimum amount of teaching experience and was selected by the program, and that a program supervisor made at least five observations of the student teaching. The gain from oversight held for both math outcomes and English language arts. Unsurprisingly, the effect did not seem to persist into the candidate’s second year on the job.

Boyd and colleagues also looked at whether simply having any student teaching experience at all mattered. Student teaching did matter for the first year of teaching math, with results being mostly inconclusive for English language arts.

State regulations of student teaching

Now, given that good practice teaching is valuable, do all students in education programs get such an experience? The answer appears to be no.

Here too, the data is very limited. I’ve put together a few pieces that are available; the news is not reassuring.

I had assumed practice teaching was a more-or-less universal requirement. (I was wrong.) Here are three questions about state regulations. See what your guesses are before looking at the answers.

How many states require:

- Student-teacher placements of at least 10 weeks?

- Placements represent a full-time commitment for the student equal to at least 12 credit hours?

- Supervising teacher must have at least three years of experience?

The answers, from the National Center on Teacher Quality’s (NCTQ) “Student Teaching in the United States”:

- 10 week placements: 27 states.

- At least 12 credit hours: 18 states.

- Experienced cooperating teacher: 11 states.

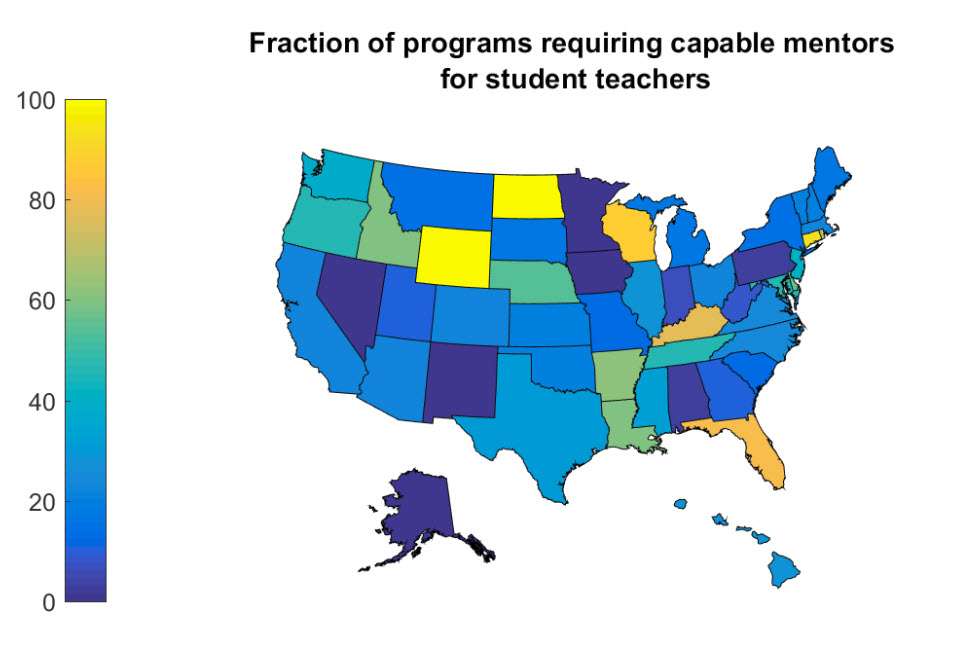

State regulations don’t necessarily describe actual practice, of course. Regulations are a minimum that we expect many programs to exceed. For a more direct look at what education schools do, I looked at a different metric on student teaching. Using NCTQ data, I calculated what fraction of education programs in each state are rated by the NCTQ as requiring a “capable mentor” for student teachers. (The NCTQ defines a “capable mentor” as one “possessing demonstrated mentorship skill or having taken “a substantial mentorship course/”) The following map ranks each state from yellow (most programs do require a capable mentor) to blue (they don’t).

Source: NCTQ, personal communication

One doesn’t see a whole lot of yellow or orange.

Making the tradeoff

It’s tough to find qualified teachers to mentor candidates through the vital step of practice teaching. If we find ourselves training fewer teacher candidates, education schools should presumably have a better shot at arranging high-quality practice teaching placements. This is especially true for schools that train a fair number of undergraduates who do not end up taking teaching positions. The available good practice teaching positions won’t have to be spread quite so thin.

When it comes to teaching, most people will argue that quality is more important than quantity. If having fewer students vying for teaching posts increases the fraction of new teachers who start their career coming off a well-mentored student teaching experience, the result of a teacher “shortage” might be less worrisome than people think.

Editor’s note: This blog post was updated on October 15, 2015 with a new version of the included map.

Commentary

Student teaching: Can we leverage the recent teacher “shortage” to students’ advantage?

October 13, 2015