The relationship between the United States and China, shaped by economic and strategic competition, is one of the most important in the world today. President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping met last year in Argentina to stave off escalating tariffs, and as the two leaders prepare to hold more extensive talks at the G-20 Summit in June, we asked Brookings experts to recommend books and articles that offer a deeper perspective on China’s rise and the U.S.-China relationship.

Defense and Security

Senior Fellow Michael O’Hanlon offered a number of recommendations, including Evan Osnos’ Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China. The book, written after the author lived in Beijing for eight years, won the National Book Award in 2014 for nonfiction and was a finalist in 2015 for the Pulitzer Prize. The National Book Foundation wrote that it “vividly depicts the hopefulness and disappointments, clarity, and confusion that we have come to recognize in China’s dazzling drive toward modernization and economic sustainability.” Osnos is a staff writer at The New Yorker and a Brookings nonresident fellow.

Senior Fellow Michael O’Hanlon offered a number of recommendations, including Evan Osnos’ Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth and Faith in the New China. The book, written after the author lived in Beijing for eight years, won the National Book Award in 2014 for nonfiction and was a finalist in 2015 for the Pulitzer Prize. The National Book Foundation wrote that it “vividly depicts the hopefulness and disappointments, clarity, and confusion that we have come to recognize in China’s dazzling drive toward modernization and economic sustainability.” Osnos is a staff writer at The New Yorker and a Brookings nonresident fellow.

O’Hanlon also recommended both Thomas Wright’s All Measures Short of War: The Contest for the Twenty-First Century and the Future of American Power, and Robert Kagan’s The Jungle Grows Back: America and Our Imperiled World.

In All Measures Short of War, Wright—a Brookings senior fellow in the Project on International Order and Strategy—explores what geopolitical competition among the U.S., Russia, China, and other rising powers will look like in decades to come. While the great powers will seek to avoid a major war, they will compete using tools such as cyber war, economic war, proxy war, and coercive diplomacy. “Russia and China are challenging the West to see where the true limits lie,” Wright observes, adding that:

Moscow and Beijing believe that the United States will remain a superpower for some time and do not buy the narrative of decline. But they also understand that the approach of broadly defined American interests to include a liberal international order has a soft underbelly—public opinion may not support costly action to defend places that American voters regard as peripheral. And they see great opportunity in Trump’s rejection of the liberal international order.

In The Jungle Grows Back, Kagan—the Stephen & Barbara Friedman Senior Fellow at Brookings—argues that American withdrawal from global affairs dangerously misreads the world, and misunderstands the essential role America has played in keeping the worst instability in check. The rise of authoritarian regimes in China, Russia, and elsewhere threatens the liberal world order so carefully tended by the U.S. and allies since the end of World War II. “Authoritarians don’t have the same vulnerability [as Communists did],” Kagan wrote. Continuing, he noted:

The case for authoritarianism during the Cold War was that it was traditional, organic, natural, yet perhaps the very naturalness of that authoritarianism makes it a bigger and more enduring threat. We have assumed that authoritarianism is a stage in the evolutionary process. But there may be no stages. Authoritarianism may be a stable condition of human existence, and more stable than liberalism and democracy. It appeals to core elements of human nature that liberalism does not always satisfy— the desire for order, for strong leadership, and perhaps above all, the yearning for the security of family, tribe, and nation. If the liberal world order stands for individual rights, freedom, universality, equality regardless of race or national origin, for cosmopolitanism and tolerance, the authoritarian regimes of today stand for the opposite, and in a very traditional, time honored way.

O’Hanlon, too, is author of numerous books and articles on global and defense affairs, including some that address the policy challenges presented by China’s growing footprint in global affairs.

In his latest book, The Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War over Small Stakes (Brookings Institution Press), O’Hanlon explores scenarios in which a local crisis could erupt into a major war between the United States and China or Russia, and offers alternatives for dealing with these risks. In the case of China, for example, both China and Japan claim a small archipelago of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea known in Japan as the Senkaku Islands, and in China as Diaoyu Islands. They are covered by the U.S.-Japan security treaty. What would be the U.S. response if China landed military forces on them?

And, in A Glass Half Full? Rebalance, Reassurance, and Resolve in the U.S.-China Strategic Relationship (Brookings), O’Hanlon and co-author James Steinberg argue that the logic of the relationship today between the U.S. and China is open to debate on both sides of the Pacific, and that the security relationship in particular needs to be readdressed. “China is seeking more prominence, prestige, and prerogatives on the world stage, commensurate with its newfound economic and military strength,” they write.

That is understandable. Yet to avoid dangerous confrontation with the United States and its partners, it can and should seek to expand its influence and clout in ways generally consistent with the international order that has helped it prosper and ascend— even if it wishes some influence over the future course of how that order is refined for the twenty- first century.

“As for the United States,” O’Hanlon and Steinberg add:

it is competing with China in many ways, to be sure, and it will have to keep competing. But its approach should not insist on dominance for its own sake, an outcome China is bound to resist. While the reassurance agenda should be pursued much more vigorously, the fact that disputes will persist should not cause either side to throw up its arms in despair over the other’s behavior.

A Glass Half Full is available to download in full.

Chinese politics

Senior Fellow Jonathan Stromseth, who holds the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asia Studies at Brookings, seconds O’Hanlon’s recommendation of Osnos’ Age of Ambition, and adds a couple more items to the reading list. In The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State, China scholar Elizabeth C. Economy examines the transformation in China today under leader Xi Jinping, and documents Xi’s “Chinese Dream” of his country’s rejuvenation. In aiming for this vision, Economy writes, “Xi and the rest of the Chinese leadership have parted ways with their predecessors” in reform efforts by rejecting opening up. “[I]nstead there is reform without opening up.”

Senior Fellow Jonathan Stromseth, who holds the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asia Studies at Brookings, seconds O’Hanlon’s recommendation of Osnos’ Age of Ambition, and adds a couple more items to the reading list. In The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State, China scholar Elizabeth C. Economy examines the transformation in China today under leader Xi Jinping, and documents Xi’s “Chinese Dream” of his country’s rejuvenation. In aiming for this vision, Economy writes, “Xi and the rest of the Chinese leadership have parted ways with their predecessors” in reform efforts by rejecting opening up. “[I]nstead there is reform without opening up.”

Stromseth is also a co-author with Edmund J. Malesky and Dimitar D. Gueorguiev of China’s Governance Puzzle: Enabling Transparency and Participation in a Single-Party State, which China Quarterly called “an excellent new book” on the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to enhance transparency and public participation—both ingredients aimed at strengthening Party rule. See also the authors and other experts participate in a public event about the book.

Stromseth is also a co-author with Edmund J. Malesky and Dimitar D. Gueorguiev of China’s Governance Puzzle: Enabling Transparency and Participation in a Single-Party State, which China Quarterly called “an excellent new book” on the Chinese Communist Party’s efforts to enhance transparency and public participation—both ingredients aimed at strengthening Party rule. See also the authors and other experts participate in a public event about the book.

Taiwan

Senior Fellow Richard Bush, the Michael H. Armacost Chair and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies, offers a recommendation related to the fraught issue of Taiwan and its relationship with China. He points to an article by Davidson College’s Shelley Rigger titled “Taiwan on (the) Edge.” Rigger writes that over the past 30 years, most of the “worst-case” thinking about potential conflict in the Taiwan Strait has not been justified. However, “[a]t this moment,” she writes, “as Taiwan’s political parties battle over their presidential nominations, I am more worried about the future of the Taiwan Strait than I have ever been. Ominous trends are building on all three sides of the triangle, and conflict could be the result. It is by no means inevitable, or even the most likely future. But for the first time in decades, I can see a plausible path to disaster in the Taiwan Strait.”

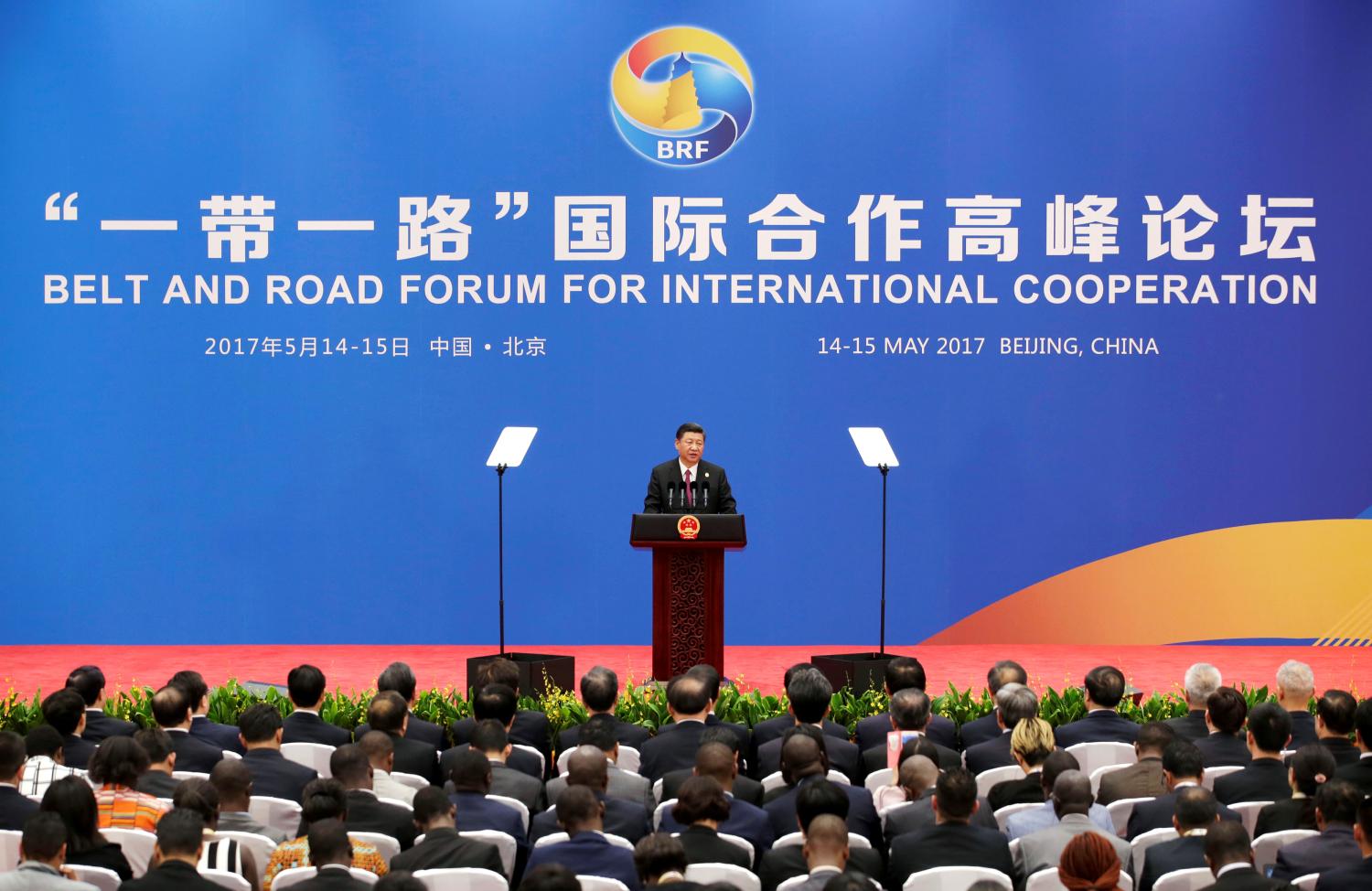

The Belt and Road Initiative

Senior Fellow David Dollar, host of the Brookings trade podcast “Dollar & Sense,” recommends a conversation among seven Brookings scholars about China’s Belt and Road Initiative. In “China’s Belt and Road: The new geopolitics of global infrastructure development,” moderated by Foreign Policy Vice President Bruce Jones, the scholars assess China’s motivations for launching BRI, its track record, the regional responses to it, national security implications for the U.S., and policy responses. Among many conclusions is that “BRI shouldn’t be seen as a traditional aid program because the Chinese themselves do not see it that way and it certainly does not operate that way. It is a money-making investment and an opportunity for China to increase its connectivity.”

Dollar also points to his article in Democracy: A Journal of Ideas, titled “Diplomacy: Can China See the Global Public Good?” In it, Dollar evaluates the “mixed record of diplomacy” across eight issues in the U.S.-China relationship. “The track record of diplomatic engagement with China is mixed,” Dollar concludes, “but it does not support the conclusion that engagement has failed. The successes all shared the characteristic that China came to see the global public good in question as clearly in its own interest. Also, intensive U.S. bilateral diplomacy was complemented by multilateral institutions. The United States cannot have much hope of changing Chinese behavior if the ask in question cannot be nested in a multilateral agreement.”

Further reading

Tarun Chhabra, a fellow in Foreign Policy, recommends Thomas Wright’s 2013 piece, “Sifting through Interdependence,” published in The Washington Quarterly. Chhabra writes that Wright “incisively—and very presciently—argues that too much interdependence in some domains can be destabilizing. Some assume more interdependence is always better—more ballast—but that’s not the case when countries’ interests and values are diverging, and yet they can still hold each other at risk in sensitive sectors.” Chhabra recommends reading the piece in the context of recent U.S. moves against Chinese telecom company Huawei, “and China’s threat to restrict exports of rare earths.”

Chhabra adds to his list The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression, by Angus Burgin. “As 2020 candidates begin to debate how the U.S. needs to reinvest in its national competitiveness vis-a-via a rising China,” Chhabra explains,

[The Great Persuasion] chronicles the ascent of hyper laissez-faire economic thought from Hayek to Reagan, and provides an excellent backdrop for a fascinating, recent IMF working paper on industrial policy, “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy,” and for Dominic Tierney’s “Does America Need an Enemy?” which previews a forthcoming book on whether America historically “needs” a formidable foreign foe to break recurrent, vicious cycles of inequality and political polarization.

“The sinews between the end of the neoliberal era, the revival of industrial policy, political realignments, and the rise of China,” Chhabra concludes, “merit much more attention.”

Chhabra is also the author of “The China challenge, democracy, and US grand strategy,” a policy brief in the Democracy & Disorder series. “China’s growth and determined illiberalism,” he argues, “mean that open societies around the world must prepare for the current era of democratic stagnation to continue, or even worsen. Against this backdrop, the United States and its allies must first come to grips with the gravity of the China challenge and then advance democracy and liberal values to the forefront of U.S. grand strategy.”

For additional research and analysis about China, visit the China topic page on the Brookings website, as well as the John L. Thornton China Center and the Center for East Asia Policy Studies.

Commentary

Brookings experts’ reading list on US-China strategic relations

June 24, 2019