During Women’s History Month, we’re highlighting contributions made by women associated with the Brookings Institution. Most of the them are scholars, but there is one woman in particular who deserves a spotlight, one of the most influential women in the long history of the Brookings Institution.

“When Washington thinks now of the Brookings benefactions it thinks of Isabel Vallé January Brookings as well as of Robert Brookings.” So wrote the Washington, D.C., correspondent of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in his 1931 feature piece of the Brookings Institution’s founder.[1] When this article appeared in the Sunday magazine, under the rubric “Interesting St. Louisans,” the couple had been married almost exactly four years, but they had known each other for decades in lives that intersected intellectually, financially, and emotionally. Through his vision, wealth, and commitment to service, Robert Somers Brookings transformed and established institutions in St. Louis and the nation’s capital. But just as he was essential to the growth and prosperity of the organizations he supported, so was Isabel Vallé January. Through her attention and financial beneficence, she was a steadfast supporter of Brookings the man and the organizations he supported, as well as a vast array of her own philanthropic endeavors.

A wealthy St. Louis childhood

Isabel Vallé January was born on April 6, 1876 in St. Louis to Jesse Lindell January and Grace Vallé, both members of wealthy and long-established St. Louis families. Jesse January’s business was real estate, but he had investments in Montana silver mines as well. When he died of pleuropneumonia at age 33 in 1883, the Post-Dispatch lamented that “St. Louis loses one of her most active and promising young business men.”[2] Grace Vallé was considered “a member of one of the most exclusive of the old French families who constitute the Knickerbockers of St. Louis.”[3] Grace’s father, too, had invested in mining (iron ore) and her mother was related to the painter John Singer Sargent. Isabel’s mother inherited wealth not only from her father’s estate when he died in 1872, but also when she became a widow weeks shy of turning 31. Isabel was their only child.

Isabel and her mother frequently traveled the country and went abroad, as did many women of their class in the late Gilded Age. They were the sort of people about whom papers reported news such as, “sailed this week for Europe” (May 1885) or “are now at the Hygenia [sic] Hotel, Old Point Comfort,” at Hampton Roads, Virginia (March 1889).

But Grace January was not simply a wealthy heiress of stocks and properties. The Post-Dispatch deemed her a woman “with brains,” one of the “St. Louis ladies who are successful in business.” Even through the Gilded Age-sexism, the paper seemed impressed. Since her husband Jesse’s death she had, explained the Post-Dispatch, “taken charge of her property herself, and now manages it almost unaided. She is worth not less than $1,200,000.”[4]

In 1890, when Isabel was nearly 14, her mother was judged by the Post-Dispatch to be the second richest woman in St. Louis (after Julia Maffitt, whose ancestors founded the city), with an estimated worth of $5 million. Her “unaided” management of her property was going well, it seemed. “Mrs. January,” the paper informed readers, “is rearing her daughter with the greatest tenderness and simplicity, and her disposition and cultur[e] will be riches in themselves.”[5]

It’s not known exactly when Robert Brookings entered Grace and Isabel’s life. He had moved to St. Louis from his birth home in Maryland in 1867, aged 17, to pursue fortune with his older brother Harry. He spent the next decade—nearly all of his twenties—as a traveling salesman for the woodenware business Cupples & Marston. In his thirties, he began to gather wealth and connections in his adopted city, perhaps including the Januarys. His biographer, Hermann Hagedorn, explained in his 1936 volume that Brookings’s “closest intimate” among the women of St. Louis “was a charming, intelligent woman in her middle thirties, a widow, Grace January.” According to Hagedorn’s account (a project instigated and reviewed by Isabel Brookings herself, who instructed the author to only be truthful), Brookings and young Isabel met in 1884 or ’85 when she was 8, a year or so after her father died. “One day,” Hagedorn explained, “as Brookings laid aside his hat and coat in the hall of [Grace’s] house, a girl slid like a tawny comet down the banisters into his arms. She proved to be Mrs. January’s daughter, Isabel, aged eight.”[6]

A life abroad

Robert Brookings and the Januarys—Grace and Isabel—visited and corresponded with each other regularly over the next few decades. As the new century dawned, Brookings left the business he had built up and became ever more involved in creative and philanthropic projects in St. Louis that pre-dated his coming to the nation’s capital. In the 1890s and into the pre-war years of the 20th century, Brookings was a leading figure in the redevelopment of Washington University, including building a new campus and transforming the medical school.

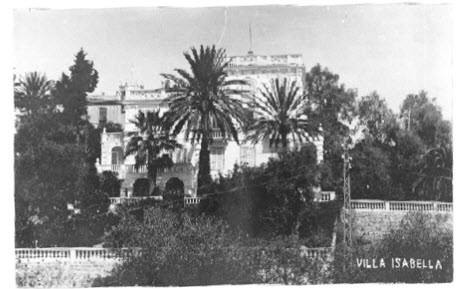

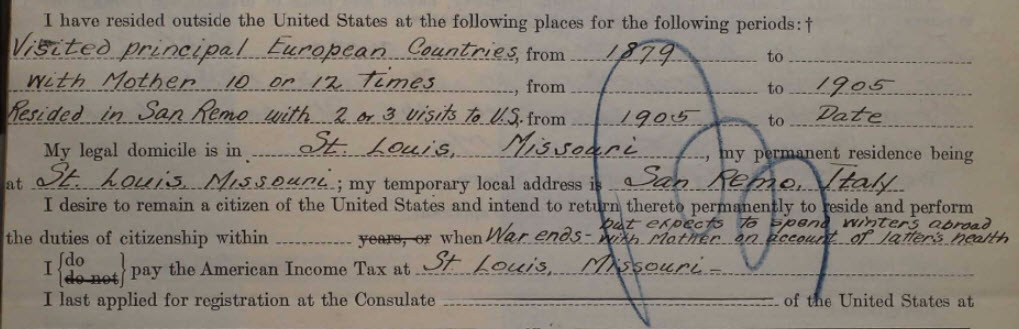

Meanwhile, Grace and Isabel January spent much of their time traveling in the United States (Maine, New York, Virginia) and in Europe. In 1906, the St. Louis-Post Dispatch reported with a four-part stacked headline that “Mrs. January to Live in Europe.” She departed New York for France with Isabel, then 32 years old, and her younger sister Isabel Vallé Austen.[7] “I am not coming back very soon,” Grace January said, “and as the climate of Italy agrees with me so remarkably well, it is possible I may not return to St. Louis.”[8] Indeed, she did not, unless only to visit, and Isabel, too, lived most of these years in Italy. As Hagedorn put it, Isabel would become “detached by long residence abroad from the American hurly-burly.”[9]

Isabel January’s philanthropy and service start to become more apparent during this period, even as the Great War erupted across Europe. Isabel and her mother seem to have remained in San Remo during the conflict. The same month as her consular application, January 1917, Isabel was recognized by the Italian Red Cross, and was cited by the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John of Jerusalem in England “for valuable service rendered during the war, 1914 to 1919.”[10] And, in February 1919, she was awarded with a lifetime membership in the American Red Cross. She and her mother also contributed to stateside fundraising campaigns during the war. Grace subscribed $10,000 to St. Louis Liberty Bonds raised during opening game of the 1918 season between the Cardinals and Chicago Cubs (no, she didn’t attend the game, but contributed through the campaign’s Women’s Metropolitan Division), and both she and Isabel gave $2,500 to the United War Work campaign of St. Louis near the war’s end.[11]

According to the curator of an exhibit put on by Brookings on the occasion of the Institution’s 75th anniversary in 1991, Isabel’s friends “called her an idealist and a linguist.”

Isabel January’s philanthropy and service start to become more apparent during this period, even as the Great War erupted across Europe. Isabel and her mother seem to have remained in San Remo during the conflict. The same month as her consular application, January 1917, Isabel was recognized by the Italian Red Cross, and was cited by the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John of Jerusalem in England “for valuable service rendered during the war, 1914 to 1919.”[10] And, in February 1919, she was awarded with a lifetime membership in the American Red Cross. She and her mother also contributed to stateside fundraising campaigns during the war. Grace subscribed $10,000 to St. Louis Liberty Bonds raised during opening game of the 1918 season between the Cardinals and Chicago Cubs (no, she didn’t attend the game, but contributed through the campaign’s Women’s Metropolitan Division), and both she and Isabel gave $2,500 to the United War Work campaign of St. Louis near the war’s end.[11]

According to the curator of an exhibit put on by Brookings on the occasion of the Institution’s 75th anniversary in 1991, Isabel’s friends “called her an idealist and a linguist.”

The philanthropic life

The end came too soon for Grace Vallé January. She died on March 8, 1919, at her villa in San Remo, aged only 66, and was interred in San Remo. She never did return to St. Louis. The estate she had inherited and nurtured there and left to her only child was valued at over $2.3 million, over $30 million in today’s dollars.[12]

By this time, Robert Brookings had come to Washington to engage on a national stage, including work on reforming the federal budget. During the war, Brookings served the nation as chair of the War Industries Board’s Price Fixing Committee, which aimed to discourage profiteering. He also trained his energies and financial resources on developing an Institute for Government Research in Washington, which opened in 1916. It was one of three organizations established through his leadership that merged in 1927 to become the Brookings Institution.

Isabel January, who had known Robert Brookings for at least 30 years by the time of the 1918 armistice, was an instrumental supporter of his early work in Washington. But first, she pursued a project at Washington University to honor her late mother with a gift of more $200,000 to the law school in 1920. “One of Washington University’s long cherished desires, that of possessing a separate building for its School of Law,” the Post-Dispatch reported, “is assured of fulfillment through the generosity of Miss Isabel Valle January.” The gift was announced by Robert Brookings, then president of the Washington University Corporation.[13] The new building, Grace Vallé January Hall, described by a law student newspaper as “a thing of beauty,” was completed in October 1923. Isabel’s total contribution may have approached $300,000.

But, Isabel January didn’t just give big to memorialize her loved ones. For example, in February 1922, during the Russian Civil War, she supported a St. Louis campaign to raise $40,000 for the purchase of 8,000 barrels of flour “to be sent to famine sufferers in Russia.” She gave $5,000 to the effort, and then returned to her home in Italy.[14]

Throughout this period, Isabel and Robert corresponded frequently in letters in which he often shared his ideas about national industry, politics, and economics. In one of the few surviving letters of his to her, dated January 1918 and in the Brookings Archives, he referenced “your and Gracie’s generous subscriptions to the ‘Hat Work’ of the Y.M.C.A.” In the early 1920s, he visited Isabel in San Remo during a trip to study industry and labor in Europe. His biographer, Hagedorn, described their relationship at this time, offering a window into the character of Isabel January:

Their friendship was a curious blending of similar ideals and dissimilar tastes, of complementary qualities and of areas of thought and emotion which the other would never wholly comprehend. He was intensely practical and could not understand what kept her in her remote paradise, perpetually trying to give her “interests,” not apprehending that, mystic that she was, she did not require “interests” to keep her contact with reality. Vaguely, he sensed that she knew a life that transcended his utilitarian standards, and he groped toward it. She, on her part, found him her window on the world. So they drew closer together.[15]

Robert Brookings began work to establish a graduate school at Washington University, with a course of study that would send students for a year of research in D.C. By this time, both the Institute for Government Research and his new Institute of Economics were operating in the nation’s capital. But legal and tax challenges thwarted his plan to have a school with shared activities in both St. Louis and Washington, so instead he focused on integrating it into the two existing institutes he had founded in Washington, D.C. “I wish you to read these papers carefully,” Robert wrote Isabel on the matter of the school, “and give me your reaction on them as, for a woman [emphasis Hagedorn’s, suggesting Brookings emphasized them himself, perhaps playfully], you have a remarkably clear head on political problems.”[16] In the same letter, he went on to explain his motives for discussing his new endeavor with his old friend: “First, because I really believe they are destined to render our country a service which it would be difficult to overvalue. And second, if your accumulating charity fund should get to a point where it is burning a hole in your pocket, I could show you any number of opportunities here in Washington for getting rid of it.” Isabel January contributed $350,000 outright to the new Robert Brookings Graduate School.

He secured the same amount but over five years from George Eastman, and just over half a million dollars over seven years from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Foundation. He pledged his own funds that yielded an annual income of over $40,000 for the school.[17] The program granted nearly 70 PhDs from 1924 to 1930, 18 of them to women.

“By this time,” former Brookings President Strobe Talbott wrote in a history of the Institution, “Isabel was an integral part of Brookings’s life. … Their correspondence and the testimony of friends leave no doubt that their friendship blossomed in part because she shared his interest in education, good works, and big ideas that rewarded entrepreneurship and benefited the lives of citizens.”[18]

In 1927, the three organizations—the Institute for Government Research, the Institute of Economics, and the Robert Brookings Graduate School of Economics and Government—merged to become the Brookings Institution. Financial support for the new entity came from the Carnegie Foundation and the continuing grants from Eastman and the Rockefeller Foundation, among others. But its offices were scattered; it needed one home. Isabel January’s generosity provided it in her donation of between $700,000 and $800,000—in addition to the support she had already contributed. The new edifice, at 722 Jackson Place on Lafayette Square just north of the White House, was also given in memory of her mother. The new headquarters was dedicated on May 15, 1931, by Dr. Leo S. Rowe, vice president of the Institution and director general of the Pan-American Union. Dr. Rowe said in his remarks that the “gift is an outward expression of that spirit of public service to which both [Robert and Isabel Brookings] dedicated their lives and which prompted their generosity to this Institution.”[19] Robert himself was too ill to attend the opening festivities.

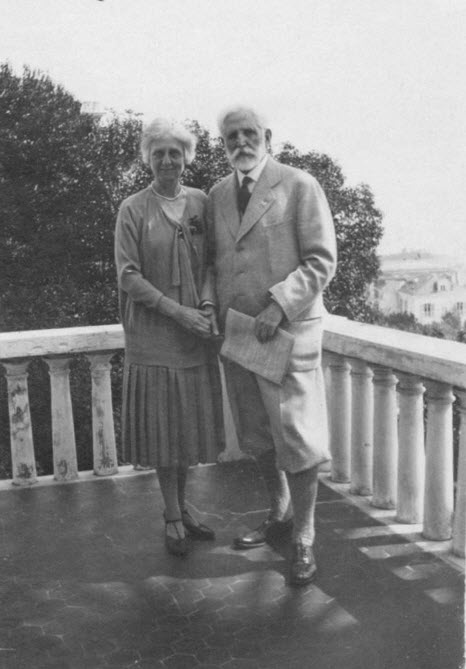

Also in 1927, a marriage took place that surprised everyone (although it shouldn’t have), but only because the couple didn’t tell anyone they were going to do it. On June 19, Robert Brookings and Isabel January drove from Washington to Baltimore and quietly became married at St. Paul’s Church. Apparently on that Sunday morning he had told Etta Cayse, his maid, simply that, “I am going to Baltimore.”[20] Some papers described the event as an elopement. He was 77, and in ill-health. She was 51. Each had been a significant part of the other’s life for over four decades. Not long before their marriage, Isabel wrote to him: “I know, Robert, that, before you have taken any important step, you have always thought it through in advance. Perhaps I’d better remind you that you yourself once told me that the one thing you had never been able to think through was marriage.”[21]

On November 15, 1932, Robert S. Brookings died in Washington. He had given not only $5 million in cash and property to Washington University and $1 million to the Brookings Institution, but also his energy and vision to creating and sustaining institutions in St. Louis and the nation’s capital that would long outlive him. According to his biographer, he told his nurse at the end, “I have done everything I wanted to do. This is the end.”[22]

But even after Brookings passed away, Isabel Brookings continued to support the Institution he created. She corresponded frequently with the Institution’s first president, Harold G. Moulton, on topics ranging from research projects, to finances, to board meetings. William Willoughby, director of the Institute for Government Research, thanked her in early 1933 for supporting his research that led to the publication of a study of the organization of Congress. “My dear Mrs. Brookings,” Willoughby wrote:

I can hardly express the extent of my appreciation of the great kindness of Mr. Brookings and of yourself in making it possible for me to bring to a completion the work which I have for years desired to write dealing with the practical problems involved in the organization and operation of the legislative branch of our government. … But for your and Mr. Brookings’ kindness, it would have been difficult for me, under the necessity that I now am of providing for the support of my family, to have devoted myself to this work.[23]

She welcomed hearing from President Moulton. While in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in June of ’33, she wrote to him that “It is always the greatest satisfaction to me when you keep me in touch with the work of the Institution by writing me about it, so please do so whenever you can spare the time.” In May 1935, she pledged $45,000 in funds to restore the Institution’s dwindling endowment. Moulton replied, “May I add my deep personal appreciation not alone of your generosity but of the understanding way in which you co-operate in our work.”

In subsequent years leading up to America’s entry into World War II, Isabel Brookings continued to support the Institution with gifts of stock and cash. In the late ‘30s, she had pledged $1 million to Brookings, and paid installments toward that pledge year after year. By 1943, according to Talbott, she had donated a further $664,000 to the Institution, and in 1944 gave a gift of $1 million for the endowment.[24]

Isabel Brookings also served on the Board of Trustees from 1949 until her death. She was only the second woman to serve on the board. “Her record of attendance at business meetings and other institution events was near perfect,” Talbott wrote.[25]

The disposition of a rare violin testifies to Isabel Brookings’s devotion to the organization her late husband founded, but also her fidelity to doing things the right way. In June 1884, Robert Brookings began a year-long sojourn to Europe, centered in Berlin. He had been from childhood, it should be noted, an avid violin player (his mother once reminded him to bring his violin home from school when he was 14). While in Berlin, studying German and music, he met a banker who was related to Mendelssohn the composer. This businessman introduced young Robert Brookings to the Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim, who counseled the aspirant that he would never succeed at the instrument unless he was prepared to devote more time to it. Brookings was not prepared for that tradeoff, so instead he purchased a fine violin from a dealer recommended by Joachim. The instrument had been crafted by Nicola Amati of Cremona in 1654. Over the years, he tried various times to sell it, but never did. Isabel Brookings inherited it upon his death. In March 1937, she wrote a letter to Harry and Robert Brookings, her late husband’s nephews, explaining her belief that the best course of action for the rare and expensive instrument was to donate it to the Library of Congress, which would also provide yet another monument of sorts to her late husband. Still, selling it remained on the table and yet, as she wrote, “if I should succeed in selling it now, of course I would instantly give the money to the Brookings Institution.” She donated it to the Library in 1938, where it remains today.

Her final gifts

Isabel Brookings took up residence at the Mayflower Hotel, just down Connecticut Avenue from Brookings’s headquarters, in her remaining years. She enjoyed oysters on the half shell once or twice a week with her financial assistant and investment counselor, Mildred Maroney, who also served as treasurer of Brookings for many years.[26]

She died the day after her eighty-ninth birthday, on April 7, 1965. Her will, a copy of which is held in the Brookings Archives, testifies to the array of charitable organizations that she supported. She left half a million dollars to Washington University in St. Louis and large sums to religious institutions, including $25,000 to her church, the Church of the Ascension and Saint Agnes in D.C.

She was hard of hearing, and so bequeathed $75,000 to various organizations involved with the deaf, including Children’s Hearing and Speech Center of Washington and the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf in Washington. She gave $25,000 to Washington Hospital Center “to be used for its Department of Ophthalmology” (plus the same sum to her doctor there for whatever use he deemed appropriate) and also authorized the “study of my ears” following her death.

The St. Louis-Post Dispatch, in her obituary, noted that she had also supported charities such the American Friends Service Committee of Philadelphia; the Animal Welfare Institute of New York City; the Movement for Federal Union (a world federation of democracies); CARE; the YWCA; and the National Cultural Center, which became the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[27]

Mrs. Brookings also took care of those who took care of her. In addition to gifts to a number of family members, including Robert Brookings’s distant relatives, and some friends, she left her butler and maid, Theodore and Marie Fahs, a monthly annuity. Finally, her will specified a gift of $40,000 to Mildred Maroney, her longtime adviser, employee of the Brookings Institution, and friend. By this time, Ms. Maroney was just a few years shy of the mandatory retirement age of 65 herself, and so this sum would have provided some retirement security for her.

Finally, Isabel Brookings bequeathed what was left of her estate to the Brookings Institution. It was a considerable sum, given all the other gifts. In 1967, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch pegged this value at $8 million, though it may have approach $10 million. At the end of 1965, the Ford Foundation put up a grant of $14 million, the largest in the organization’s history. “With these major grants,” per a history of Brookings at its fiftieth year, “the Institution had already surpassed the $20 million capital development goal President [Robert] Calkins had hoped to reach by 1968.”[28]

Isabel Vallé January Brookings was born into a life of privilege, a girl whose ancestors were men and women of enterprise and means, the “Knickerbockers” of St. Louis. Tragically, she lost her father when she was just 7, perhaps then forging a bond with her mother that would last a lifetime, and perhaps then opening space for the entry into her and her mother’s life of a young businessman from Maryland. She lived about a quarter of her life overseas, but supported organizations and people around the United States. Her financial contribution to the nascent Brookings Institution was instrumental in its early success, as were her continued support and the enormous gift to Brookings at the end of her life, which coincided (less a year) with the organization’s 50th anniversary. But she was not just a financial benefactor of this and other institutions. She was as devoted to the success of these organizations as she was to the man who used his resources to create them, Robert Brookings. “She appeared, in her gentleness, compliant and acquiescent,” Hagedorn wrote, “yet she was his match in determination.” When Robert said he wanted to commission a painting of Grace January for the building at Washington University’s law school her daughter had financed and dedicated to her, Isabel asked him not to, and that she would destroy any such picture that he had made. He had one painted. Isabel did what she promised.[29]

Thank you to Brookings Institution Senior Research Librarian Sarah Chilton, the archivist of the Brookings Institution, for her insight, guidance, and support of this post. Also, thanks to Emily Rabadi and Amanda Waldron for reading and providing their feedback.

Notes:

[1] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (June 7, 1931), p. 68.

[2] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (May 10, 1883), p. 4.

[3] Chicago Tribune (December 18, 1887), p. 9.

[4] St Louis Post-Dispatch (February 26, 1888), p. 24. The sexism of the age is apparent despite the article’s emphasis on the business acumen of the featured women: “A glance at the history of a few of the most prominent leaders in society will convince the most skeptical that, not only are they fitted to preside over the home, but possess an insight into the intricacies of commerce, of which the ablest man might well be proud.” The same edition carried the thoughts of the city’s leading men on the subject of ladies’ teas “and all the other mild forms of feminine dissipation.”

[5] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (March 9, 1890), p. 17. Insofar as Isabel January’s philanthropy was enabled by the wealth she inherited from her mother when Grace died in 1919, the objects of her charity might have been grateful that Mrs. January did not tie up her fortune with a second husband, though that nearly came to pass. Besides foreign travel, another common occurrence of the Gilded Age in the Anglo-American world was the marriage of wealthy American women to impecunious but titled, or at least well-connected, British men. As the Chicago Tribune reported from St. Louis in late August 1890, Grace January was set to do just that with a marriage to Englishman Richard Frewen, whom she had met while abroad following the death of her mother, Isabelle Sargent Vallé, the year before. (Richard Frewen was a brother of Moreton Frewen who in 1881 had married Clara Jerome, who was sister to Jennie Jerome, who in 1874 had married Lord Randolph Spencer-Churchill and would later become mother of Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill). A week later, news reached the American press that the engagement was off. The attorneys of the two parties had determined that Jesse January’s will provided that should Grace die after re-marriage, her property would go not to the second husband, but to her daughter Isabel. This circumstance “is said to have been so unsatisfactory to Mr. Frewen that he withdrew all pretensions to the lady’s hand.” (The Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel (September 3, 1890), p. 10.

[6] Hermann Hagedorn, Brookings: A Biography (Macmillan, 1936), pp. 107-08.

[7] Isabel Valle Austen was a subject of a painting by John Singer Sargent, once owned by Robert and Isabel Brookings, and now in a private collection. See it at: https://www.johnsingersargent.org/Isabel-Valle.html

[8] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (November 29, 1906), p. 2.

[9] Hagedorn, p. 173.

[10] Certificate in Brookings Archives.

[11] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (April 17, 1918), p. 3; St. Louis Post-Dispatch (November 27, 1918), p. 1.

[12] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (July 2, 1919), p. 10.

[13] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (October 17, 1920), p. 70.

[14] St. Louis Star and Times (February 27, 1922), p. 17.

[15] Hagedorn, pp. 272-73.

[16] Sarah Booth Conroy, “Brookings and the Institution of Marriage,” The Washington Post (February 9, 1992).

[17] Charles B. Saunders, Jr., The Brookings Institution: A Fifty-Year History (Brookings, 1966), pp. 33-34.

[18] Strobe Talbott, “Their Big Idea: Our Founders’ Vision as a Guide to Brookings’s Second Century” (Brookings, 2015), p. 28.

[19] Evening Star (May 16, 1931), p. 3.

[20] Hagedorn, p. 300.

[21] Hagedorn, p. 298.

[22] Hagedorn, p. 315.

[23] Letter, William Willoughby to Isabel V. Brookings (January 9, 1933), Brookings Archives. The study, Principles of Legislative Organization and Administration, was published by Brookings in 1934.

[24] Talbott, p. 40.

[25] Talbott, p. 40.

[26] The Daily Oklahoman (December 17, 1963), p. 9. Mildred Maroney, who grew up in Stillwater, Oklahoma and came to Washington in 1926 on a fellowship, had also been assistant to Robert Brookings. She worked at Brookings for 43 years, including 21 as treasurer.

[27] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (April 8, 1965), p. 31.

[28] Saunders, pp. 107-08.

[29] Hagedorn, p. 302.

Commentary

The philanthropic life of Isabel Vallé Brookings

March 14, 2019