“In the end, the future of manufacturing in America is going to be high-value, high-tech, and more automated—dominated by new production technologies and fast-evolving supply chain practices.” – Mark Muro, Senior Fellow

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump cited the loss of American manufacturing jobs and seemed to lay the blame on globalism and what he characterized as unfair trade practices. After his election victory, the president-elect has continued to focus on manufacturing with tweets and statements about specific companies and jobs, including Carrier in Indiana and Ford Motor Co. in Michigan. What are the facts about changes in U.S. manufacturing jobs and policy ideas to meet the challenges facing this sector? Experts from across Brookings continue to offer their analysis and ideas. Here are some:

The inflation-adjusted output of the manufacturing sector is at an all-time high

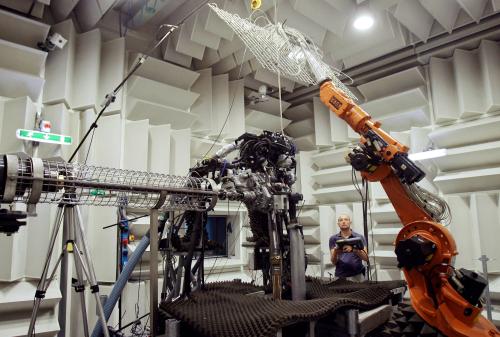

Mark Muro, senior fellow in Metropolitan Policy, and Research Assistant Sifan Liu write that American manufacturing productivity is higher than ever due to automation and increased efficiency. “In 1980,” they note, “it took 25 jobs to generate $1 million in manufacturing output in the U.S. Today, it takes just 6.5 jobs to generate that amount—and that’s after five more stable years of little change.”

This is one reason why President Donald Trump won’t be able to bring back millions of factory jobs, they say. “[T]o hang frustrated workers’ hopes of relief on large-scale hiring in an increasingly automated, hyper-efficient manufacturing sector appears to be severely misdirected,” Muro and Liu argue.

Robots are not stealing manufacturing jobs

Centennial Scholar Associate Fellow Scott Andes writes that, despite belief to the contrary, at the national level “there is no correlation between adoption of robots and job losses in the manufacturing sector.” Instead, he argues, automation changes jobs in various ways. Instead of focusing on the so-called “job-stealing robots,” Andes observes that the “Americans being displaced by robots and automation lack critical skills needed in the future economy, and little is being done to support these workers or prepare disadvantaged students.”

Policymakers, the media, and voters, Andes argues, “should see automation as a call for education, and they should embrace automation as a way to capture new global markets and improve our overall competitiveness.”

In an earlier analysis, Andes and Muro pointed to cross-national data that showed that some countries like the United Kingdom and Australia that invested less in robots saw faster declines in manufacturing jobs, while countries such as Germany and Sweden that have much higher intensities of automation than the U.S. shed fewer manufacturing jobs than the U.S.

Manufacturing employment failed to improve last year for the first time in seven years

Economic Studies Senior Fellow Gary Burtless looked at the November 2016 job report and noted that manufacturing (and mining) payrolls dropped 54,000 from December 2015 to November 2016, the first decline in seven years in that sector. The “good news” from the year, Burtless said, was “that unemployment continued to fall and real wages continued to improve.” However, the labor force participation rate remained 1.5 percentage points below its level of November 2007, a trend concentrated among men. “The anemic rebound in the labor force participation rate,” Burtless concluded, “suggests the nation may not be able to find enough willing job holders. In that case, we cannot expect future job gains to continue at the pace we have seen for the past few years.”

Millions of lost manufacturing jobs are not coming back to America

Muro acknowledges that the 30-year drop in manufacturing employment from 18.9 million to 12.2 million jobs, concentrated in Midwestern and Rust Belt states, contributed to Donald Trump’s electoral success. However, manufacturing productivity is increasing, and except for the past year, manufacturing employment has increased since 2010. Muro writes that the “automated, hyper-efficient shop floors of modern manufacturing won’t give Trump much room to deliver on his outsized promises to bring back millions of jobs for his blue-collar supporters.”

Instead, any response to this issue must include “investing in manufacturing innovation … ensuring that workers get industry-relevant training that equips them for today’s digital factors [and] supporting the nation’s regional advanced industries clusters.”

Three economic trends will prevent long-term reversal of manufacturing employment decline

David Dollar, a senior fellow in Foreign Policy and Global Economy and Development, cites three global economic trends that will likely hold back any long-term restoration of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. These include technological change—which Dollar cites as the primary cause of manufacturing job loss and that can be seen across the advanced economies, such as Germany—as well as the trade balance and its relationship to investment, and finally the inefficacy of potential trade restrictions under a Trump administration. While a “one-time increase” in manufacturing jobs could ensue from a decline in the trade deficit, Dollar argues that “it is extremely unlikely that any set of U.S. policies could reverse the long-term trend for manufacturing employment to fall as a share of the labor force, hence the importance of policies to support training and adjustment.”

Manufacturing jobs comprise over 44 percent of jobs in the “advanced industries” sector

Researchers from the Metropolitan Policy Program detail the extent of America’s “advanced industries” sector, which features 50 industries “that conduct significant R&D and employ a disproportionate number of STEM workers.” These workers are found in auto making, aerospace, energy, oil and gas extraction, high-tech services, and other industries. “[T]he flow of technology use and business transformation among the advanced industries,” the researchers say, “appears to be erasing conventional industry and sector distinctions and turning the super-sector into the leading focal point of technology convergence in developed economies.”

Read “America’s advanced industries: New trends,” for new analysis and data—including metro-specific data—on advanced industries in America.

The “maker movement” is one way American communities can rebuild manufacturing

Mark Muro describes five ways that the maker movement—technology-influenced, DIY engineers, artists, crafters, and scientists—can “help catalyze a manufacturing renaissance.” He points to how the participants in this movement have “employed online tools, 3-D printing, and other new technologies to ‘democratize’ manufacturing and reinvigorate small-batch production and sales,” helping to create new value and spur innovation.

“In city after city, region after region,” Muro writes, “the movement offers a practical, inclusive, all-hands-on-deck approach to preparing for and shaping the future of manufacturing.”

The Trade Adjustment Assistance program needs to be updated

Muro and Joseph Parilla, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program, write that “the nation should ensure the [TAA] program works in light of the current tide or worker frustration,” but that it “doesn’t work that well” at helping workers displaced by trade. While they argue that this program should be fixed, the larger issue is that U.S. adjustment programs as a whole are too small, narrow, and reactive to meet the unprecedented scale of labor market disruption. Muro and Parilla suggest, among other policy ideas, the creation of a “Universal Basic Adjustment Benefit” as a model of a “single, holistic, multipurpose, adjustment benefit.”

Protect American workers through safety nets and transition assistance, not protectionism

Dany Bahar, a fellow in Global Economy and Development, says that President-elect Trump’s proposal to impose a 35 percent tariff on imports from firms based outside the U.S. will not protect American workers. “Not only will it not protect the American worker,” Bahar writes, “it will strongly hurt the American consumer. This is simply because if imports turn out to be more expensive than before, it is the American consumers, and no one else, who will have to pay for that extra 35 percent that will be added to goods’ price tags.”

Plus, import tariffs would quite possibly be met with retaliation by America’s trade partners, which would put U.S. export jobs at risk, he explains. Insofar as the trade imbalance does not account for most manufacturing job losses (again, higher labor productivity and technology/automation are larger contributors), Bahar argues that “the right course of action to protect American workers is not to protect the U.S. from foreign competition but rather to put proper safety nets in place to assist affected workers in their transition to new jobs in advanced manufacturing or the service sector, or even to retirement.” The bottom line, he says, is that trade protectionism will “harm the most important determinant of economic growth: productivity.”

Learn more about U.S. manufacturing, advanced industries, innovation, and more:

Look to advanced industries to help drive productivity gains

Auto slowdown signals narrowing of advanced-sector growth

Commentary

9 things to consider about U.S. manufacturing jobs

January 12, 2017