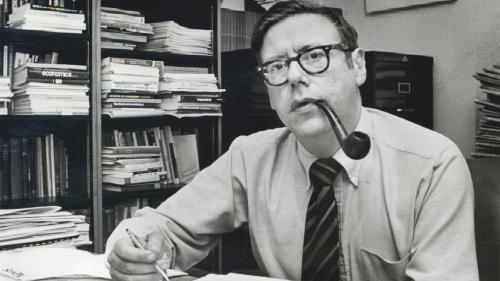

“It will not do to have a country divided by a bitter campaign, paralyzed by uncertain leadership in the awkward interval between election and inauguration, and turned over to a disorganized, ill prepared administration on January 20th.” So wrote Laurin Henry, a Brookings research associate, in a draft of his 1960 book, “Presidential Transitions.” As President Barack Obama prepares to hand the White House and the executive branch over to President-elect Donald Trump, the ideas explored and lessons learned in Brookings’s research on presidential transitions in another era remain relevant today. Henry’s book plus a series of memos prepared before the election of 1960 by bi-partisan Brookings advisory group— that would be presented to the eventual winner—were two of the most prominent expressions of Brookings research and recommendations in this field.

Henry’s work on “Presidential Transitions” began in the late 1950s as he sought approval and funding to pursue the research. He wrote his volume as a study of four presidential transitions in the 20th century: Taft to Wilson (1912-13); Wilson to Harding (1920-21); Hoover to Roosevelt (1932-33); and Truman to Eisenhower (1952-53). “Regardless what preparations they may separately make,” Henry concluded, “the outgoing and incoming Presidents share responsibility for the transfer of the reins of authority and for safeguarding the public interest during the process.” (Henry, p. 719)

Henry examined the four transitions in great detail and offered practical advice drawn from the historical record. For example, he recommended a conference at the White House between the president and president-elect, as happened in 1932 and 1952 (and would happen in 1960, and will happen between Obama and Trump). He called for assigning an “observer on behalf of the President-elect to the Budget Bureau” from after the election to inauguration day to allow the incoming administration to be “well informed.” Also, Henry proposed having observers from the president-elect’s transition team in the major agencies. “Other helpful steps,” Henry wrote, “would include the preparation in the departments of briefing books and memoranda for the President-elect and his appointees; oral briefings … and direct consultations between incoming officials and their outgoing ‘opposite numbers.’” He also suggested the possibility that at least one major political officer in each department “carry over for a greater or lesser time into the new administration.” (Henry, pp. 719-21)

Henry focused on the particular importance of national security and the budget. The “President and his successor,” he wrote, “do share a moral obligation for safeguarding the national safety and welfare in moments of crisis, because effective political power is divided between them.” And he called for special attention to the budget because the outgoing administration would have submitted a budget and the incoming administration would have to revise and act on it.

While the president-elect has to get up to speed to take the oath of office, the outgoing president and the incoming president share a responsibility. As Henry argued, “the President must not attempt to transfer his responsibility for making decisions to the President-elect.” However, sometimes “the issues may be of such surpassing importance that the risk involved in letting the President carry his burden alone becomes intolerable.” (Henry pp. 724-25)

While Henry’s book was published after the election, his research supplemented and informed the work of a Transition Advisory Committee of 13 men assembled by Brookings President Robert Calkins. The participants were or had been Brookings scholars, presidential advisers, business executives, and included, among others, the president of Corning Glass Works; the publisher of “Life” magazine; the former secretary of health, education, and welfare; and the board chairman of General Dynamics. This commission arose simultaneous to Senator Kennedy asking former White House counsel Clark Clifford and political scientist Richard Neustadt to conduct pre-transition planning. Just after his nomination, Kennedy learned of the Brookings review of past transitions and asked Clifford to attend the discussions.

Each of the campaigns and the White House assigned a liaison to the group: Bradley Patterson represented the Eisenhower administration; Brigadier General Robert Cushman, Jr. represented Nixon; and Clark Clifford represented the Kennedy camp. Brookings scholar George Graham led the advisory group in the preparation and review of nine confidential memos to be presented to whichever candidate—Nixon or Kennedy—won the election.

On September 26, 1960, Clifford wrote to Henry about the page proofs that Henry had sent him from his book: “I am,” Clifford wrote, “finding it most valuable from the standpoint of gaining the historic background in preparation for the task that confronts us.”

The memos covered a range of topics, including priorities for the next president, the cabinet, the Budget Bureau, and the regulatory commissions. As historian James Allen Smith put it: “The confidential papers—quite different from the public agendas and well-promoted policy pronouncements now emanating from think tanks each election year—dealt with both issues and administrative decisions. They opened the door for Brookings scholars to participate in some of the early planning groups and task forces assembled by the Kennedy administration.“ (Smith, p. 46)

In the first memo, “Priorities for the President-elect,” the authors detailed “the early decisions which the President-elect will face” in the areas of personnel, program, and executive action. But they underscored their analysis with a stark reminder of the short-time period from election to inauguration and the stakes involved:

According to one expert on White House staff, Eisenhower, though no fan of John Kennedy, “viewed his role in the transition as nonpartisan. Whoever captured the presidency, Eisenhower reasoned, should have access to information on departmental programs and budgets.” (Warshaw, p. 162)

The nine memos were presented to President-elect Kennedy on November 18, 1960. Theodore Sorensen, special counsel to Kennedy, later said that Brookings “deserves a large share of the credit for history’s smoothest transfer of power between opposing parties.”

Brookings followed up these contributions to helping subsequent presidential administrations transition into power, including “Agenda for the Nation,” under the leadership of President Kermit Gordon and meant to inform the 1968-69 transition; the 2008-09 transition, which included Steve Hess’s practical guide, “What do we do now? A workbook for the president-elect”; and today’s Transition 2016 project.

Laurin Henry’s book on presidential transitions has remained an influential and often-cited work on the history of presidential transitions. When it was published, Rep. Gerald R. Ford, Jr. (R-MI), asked for a copy of the book after he saw a review of it in the “New York Times.” He later wrote to Brookings President Calkins that he was “extremely pleased to have this fine publication and look forward to much pleasure in reading it.”

Also, former President Harry Truman wrote to Henry, stating that “I have been reading it with pleasure.”

“It would be a considerable step forward,” Henry wrote in his book, “if future candidates and political managers could stop thinking of campaigning and organizing an administration as completely separate jobs, with a sharp break at election day. The candidate who fully recognizes the continuously unfolding nature of these political processes, and shapes his campaign plan and organization with some attention to the position he will be in after election day, is well started on his task.” (Henry, p. 711)

We are now at the start of a new presidential transition. “It is no secret,” President Obama said the day after Donald Trump won the 2016 contest, “that the president-elect and I have some pretty significant differences. But, remember, eight years ago President Bush and I had some pretty significant differences. But President Bush’s team could not have been more professional or more gracious in making sure we had a smooth transition so that we could hit the ground running … So I have instructed my team to follow the example that President Bush’s team set eight years ago and work as hard as we can to make sure that this is a successful transition for the president-elect.”

Thanks to Brookings Senior Research Librarian and archivist Sarah Chilton for her comments and research assistance.

Sources

Henry, Laurin, “Presidential Transitions” (The Brookings Institution, 1960).

Smith, James Allen, “Brookings at Seventy-Five” (The Brookings Institution, 1991).

Warshaw, Shirley A., “Guide to the White House Staff” (CQ Press, 2013).

Commentary

What Brookings did for the 1960 presidential transition

November 9, 2016