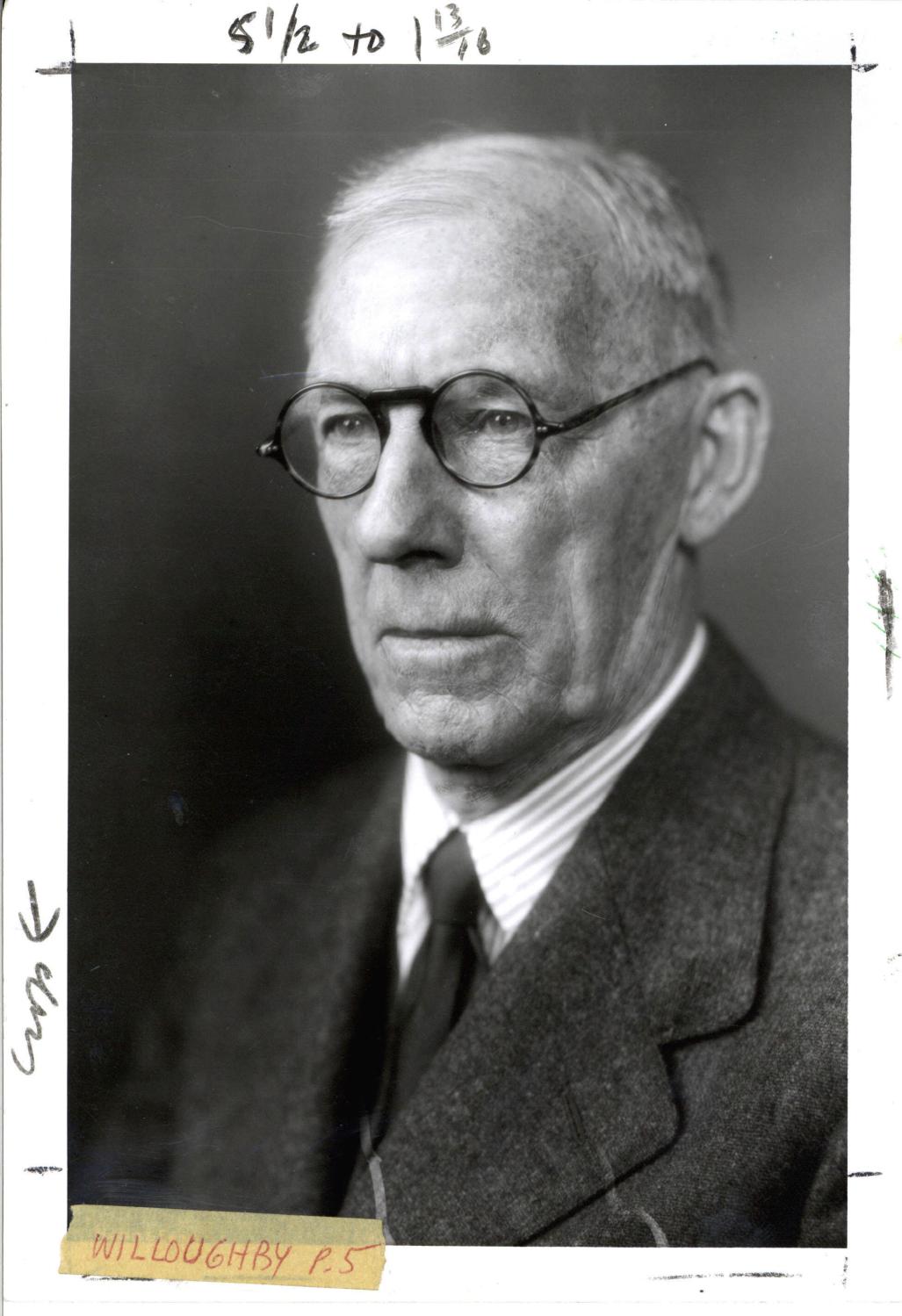

“I do not think that anyone can fairly say that the United States Government has a budgetary system.” On September 22, 1921, William F. Willoughby, director of the Institute for Government Research (IGR) in Washington, DC, testified to a House Select Committee on the Budget on the “Establishment of a National Budget System.” Willoughby had, for many years, been concerned with the problem of the lack of a national budget system and, as director of the still-new research organization—the forerunner of today’s Brookings Institution—he was well-position to offer his expert recommendations on legislation that would become the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921.

Prior to 1921, the U.S. federal government had no unified budget. No annual and centralized executive branch budgeting process existed. The agencies of the federal government sent budget requests independently to myriad congressional appropriations committees. “The appropriation committees,” according to a 1930 research report, “became partisans of the particular departments committed to their care and sought, in the hearings on the estimates, to make out the best possible case for the grants requested instead of seeking to shed light on the efficiency of departmental administration” (Granger).

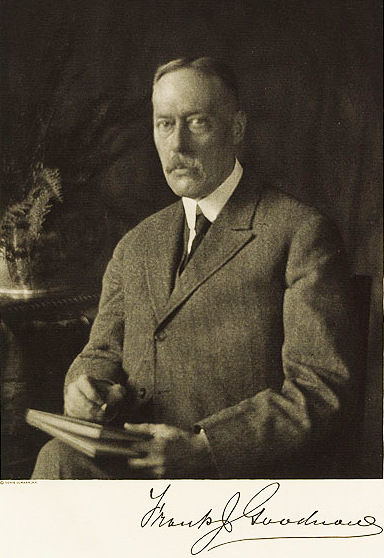

Interest in reform of the budget process was becoming widespread in the nation’s capital in the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1910, President William Taft had called for a commission on reforming government administration, with particular attention on a national budget. The newly-formed Commission on Economy and Efficiency, or, the Taft Commission, included two men who would later play a large role in the establishment of the Institute for Government Research: Frank Goodnow, a law professor at Columbia University who would become the first chairman of IGR’s board in 1916; and William Willoughby, then assistant director of the U.S. Census Bureau and who had previously served as treasurer of Puerto Rico and advised the president of China on reform matters. Additionally, businessman Robert S. Brookings served as a consultant to the commission and was later first vice-chairman of IGR’s board.

In 1912, President Taft presented the commission’s report to Congress, “The Need for a National Budget.”

“The Taft Commission soon ran afoul of Congress,” noted a 1956 Brookings-published review of IGR’s research achievements. “The new form of budget struck at the powers of key congressmen, notably those who headed the seven appropriations committees. Congress rejected Taft’s new budget, and ordered the heads of departments and agencies to prepare and submit estimates in no other way than that in which Congress requested them.” Although the work of the commission came to naught in terms of legislation, Goodnow, Willoughby, and others continued their efforts on government reform in the subsequent years, including participation in a proposal to create a new, national research organization—which became the IGR.

Support for reforms in a national budget continued to grow in Washington, and was increased by the outbreak of World War I in 1914 as federal government expenses—even then in deficit—accelerated during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson, starting in 1913. This ran concurrent with the opening of the Institute for Government Research in 1916 and its first research publications, which included studies on the budgetary systems of Great Britain (Willoughby, Willoughby, and Lindsay, 1917); France (Stourm, 1917); and Canada (Villard and Willoughby, 1918). “Prior to the organization of the Institute,” reads a 1922 IGR pamphlet on its publications, “the United States, alone among the great nations of the world, was attempting to handle its financial affairs without making use of a budget as its central instrument around which all of its financial operations should revolve.”

Then, in 1918, IGR Director Willoughby authored “The Problem of a National Budget,” which the 1922 pamphlet described as “the first serious attempt to consider this problem in both its theoretical and purely practical aspects as a concrete problem confronting the National Government.”

Following this, Iowa Republican James Good, chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, looked to Willoughby to help draft a new budget bill and the IGR director provided testimony to Good’s committee in 1919. (This was a blurring of the line on independence which later clarified and has remained bright and clear for the Brookings Institution to this day.) The so-called “Good Bill” provided that only the president, not the independent agencies, should transmit a budget to Congress; established a Bureau of the Budget under the president; and placed a comptroller general also under the president, but permitted that official’s removal by Congress. Although the Good Bill passed both houses of Congress by large majorities, President Wilson objected to the legislature’s power over his comptroller general, and so vetoed the bill.

1920 saw the election of Warren Harding and a new administration in Washington. A new budget reform bill, again drafted by Chairman Good, maintained the essential provisions of the previous bill but changed Congress’ oversight power with regard to the comptroller general.

In his September 1921 testimony to the House Select Committee, Willoughby said that he “recognized that the problem which confronts our National Government is a special one, arising out of our political system and the special difficulties encountered in seeking to frame a scientific budget system for it.” Continuing, he said that “I think it is possible for the President to prepare a budget in such a way that the Congress and the public would grasp its meaning, even the man on the street.”

In his September 1921 testimony to the House Select Committee, Willoughby said that he “recognized that the problem which confronts our National Government is a special one, arising out of our political system and the special difficulties encountered in seeking to frame a scientific budget system for it.” Continuing, he said that “I think it is possible for the President to prepare a budget in such a way that the Congress and the public would grasp its meaning, even the man on the street.”

The bill passed and was signed into law by President Harding on June 10, 1921. In his State of the Union address on December 6, 1921, President Harding said that the preparation of the first budget under the act “is a signal achievement” and “will mark its enactment as the beginning of the greatest reformation in governmental practices since the beginning of the Republic.”

The law established the Bureau of the Budget—now the Office of Management and Budget—and the General Accounting Office—now the Government Accountability Office (home of the comptroller general), both within the executive branch.

As Willoughby himself wrote in 1927 about the old system:

in scarcely a single respect did this system conform to the essential requisites of a sound system of national finance. No attempt was made to consider the whole problem of financing the government at one time. Expenditures were not considered in connection with revenues. Even the idea of balancing the budget did not exist. … Though the law required all the estimates to be submitted by the Secretary of the Treasury, that officer acted as a mere compiling authority; he had no power to modify proposals transmitted to him by the heads of the administrative departments. The estimates thus represented little more than the individual desires of the department heads. … Their financial needs being met from a common fund, each inevitably sought to secure as large a share as possible.

The budgetary system of the United States government has altered dramatically in the years since the work of William Willoughby and his colleagues in the Institute for Government Research. In current dollars, U.S. government spending in 1916 was about 2 percent of what it is today, and the scope of federal agencies is far greater than it was a century ago. There is today a Congressional Budget Office, established in 1975 and first helmed by Alice Rivlin, now a Brookings scholar. “The modern presidency,” wrote James Sundquist in a 1981 Brookings book, “judged in terms of institutional responsibilities, began on June 10, 1921, the day that President Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act.”

SOURCES

Critchlow, Donald T. The Brookings Institution, 1916-1952: Expertise and the public interest in a democratic society (Northern Illinois University Press, 1948), pp. 28-38.

Granger, G. “The national budget system,” Editorial research reports 1930 (Vol. IV), (Washington, DC: CQ Press)

Smith, James Allen. Brookings at Seventy-five (Brookings Institution Press, 1991), pp. 10-14.

Sundquist, James. The Decline and Resurgence of Congress (Brookings Institution Press, 1981), p. 39.

“Institute for Government Research: An Account of Research Achievements” (Brookings, 1956).

“The Institute for Government Research: Its organization, work, and publications” (IGR, 1922).

Willoughby, William. The National Budget System (Institute for Government Research, 1927), pp. 8-11.

Commentary

Brookings’s role in “the greatest reformation in governmental practices”—the 1921 budget reform

October 12, 2016