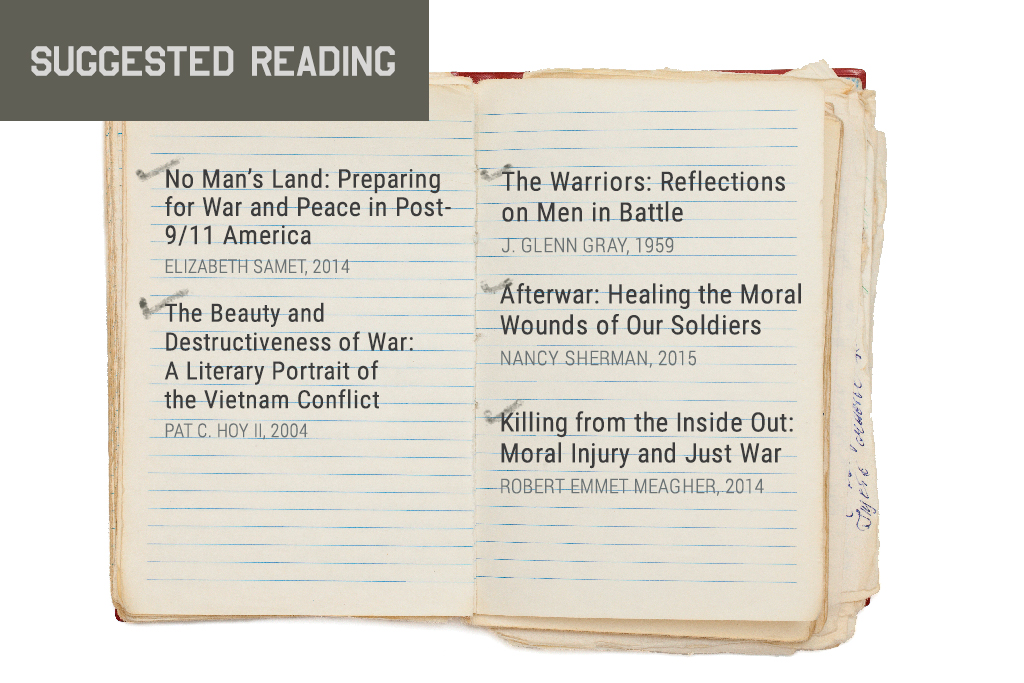

In a new Brookings Essay, “The citizen-soldier: Moral risk and the modern military,” National Book Award-winning author Phil Klay explores the complex relationship and tensions between members of the military and the civilian world. “In some ways,” Klay, a USMC veteran of the Iraq war, writes, “joining the military is an act of faith in one’s country—an act of faith that the country will use your life well.” Throughout the essay, Klay brings to bear a large volume of material—including historical documents, novels, contemporary analysis, and philosophy—to illuminate and drive his narrative forward. This reading list is by no means a comprehensive collection of war- and military-related material, but offers a deeper dive into the themes and ideas Klay explores in the Brookings Essay.

On the “sense of a personal stake in war that the veteran experiences viscerally, and which is so hard for the civilian to feel,” Klay describes how philosopher Nancy Sherman “explained post-war resentment as resulting from a broken contract between society and the veterans who serve.” As Sherman wrote about veterans’ homecomings in “Afterwar: Healing the Moral Wounds of Our Soldiers”:

We are a part of the homecoming—we are implicated in their wars. They may feel guilt toward themselves and resentment at commanders for betrayals, but also, more than we are willing to acknowledge, they feel resentment toward us for our indifference toward their wars and afterwars, and for not even having to bear the burden of a war tax for over a decade of war

Klay, the author of the critically acclaimed short-story collection “Redeployment,” winner of the 2014 National Book Award, served as a public affairs officer in Iraq’s Anbar Province in 2007 and 2008. He asks in the Brookings Essay, “What is the saving idea of Iraq?” Veterans who served in that conflict, and any other, cannot “pretend” that they have “clean hands,” writes Klay. “… Iraq is destroyed, there is untold suffering overseas, and we as a country have even abandoned most of the translators who risked their lives for us.” And yet, he adds, “this fact seems not to have penetrated either the civilians we come to, or the government that sent us.” Here, Klay references humanities professor Robert Emmet Meagher, who explored the universal acceptance of “just war” doctrine. As Meagher wrote in “Killing from the Inside Out: Moral Injury and Just War”:

How many emperors, kings, princes, presidents, politicians, or, yes, popes, who have put their lips to the horn of war have suffered from, or at least complained of, moral injury from war? Closer to home, in the recent wars of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, how many American presidents, or members of Congress have suffered from PTSD or taken their own lives rather than live any longer with the burden of having declared a war?

“None, of course,” answers Klay.

How do those who have served in war see themselves in relation to the conflict in which they served? Klay notes that many veterans wonder “What was this all for?” and answer the question by “narrowing their focus” from the national level to their own local experience. Here Klay draws upon the writing of Elizabeth Samet, a West Point instructor, who studied how soldiers contend with issues of war and peace in “No Man’s Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America.” Samet wrote of an “ancient strain in today’s war story”:

The lack of an exit strategy and the apparent absence of a clear and consistent political vision guiding the war effort—What does victory look like?—forced many of the platoon leaders and company commanders I know to understand the dramas in which they found themselves as local and individual rather than national or communal. The ends they furnish for themselves—coming home without losing any soldiers or, if someone has to die, doing so heroically in battle—offer exclusively personal and particular consolations that make the mission itself effectively beside the point.

“[P]eople join the military to be a part of something greater than themselves,” Klay writes in the Brookings Essay, “and ultimately it’s deeply important for service members to be able to feel their sacrifices had a purpose.” Those he served with, Klay describes, participated in “small moments of communal satisfaction” to try to “come to terms with the extent of our failure in Iraq.” Here, Klay turns to Pat C. Hoy II, a New York University professor and Vietnam veteran, who, in the essay “The Beauty and Destructiveness of War: A Literary Portrait of the Vietnam Conflict” (in Josephine Hendin, ed., “Concise Companion to Postwar American Literature and Culture”), wrote about “the saving rituals [soldiers] performed together” to recover from battle, including:

Burying the dead, policing the battlefield, stacking ammunition, burning left-over powder bags, hauling trash, shaving, drinking coffee, washing, talking as they restored order and looked out for one another’s welfare.

And yet, as Klay notes, citing Hoy, this “purifying idea” is not enough: “Those men had done the soldiers’ dirty job in a war that will probably never end—for them or for this nation.,” Hoy wrote. “That loneliness is what they get in return for their gift of service to a nation that sent them out to die and abandoned them to their own saving ideas when they came home.”

Klay’s source material reaches back to the American Revolutionary War, carries through the Civil War, and into the twentieth century and later. How do veterans who have served in battle discover redemption and “genuine growth as a human being?” Klay asks, and answers with the words of J. Glenn Gray, a philosopher and World War II veteran. In “The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle,” Gray wrote that, for a soldier:

guilt can teach him, as few things else are able to, how utterly a man can be alienated from the very sources of his being. But the recognition may point the way to a reunion and a reconciliation with the varied forms of the created. … Atonement will become for him not an act of faith or a deed, but a life, a life devoted to strengthening the bonds between men and between man and nature.

Klay goes on to say how this notion “is a way of thinking distinctly at odds with stories of uncomplicated military glory,” thus continuing his exploration of the tension inherent in military service—both for veterans in relation to each other and their wars, and between veterans and civilians.

Klay ends his Brookings Essay on a hopeful note, describing the many ways veterans of today’s wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere come home and continue to offer their services to their communities and countries. “The divide between the civilian and the service member,” Klay writes, “need not feel so wide.” Read the Brookings Essay here, and explore more deeply the diverse and interesting materials Klay has brought to bear.

Full bibliography for “The citizen-soldier: Moral risk and the modern military,” a Brookings Essay by Phil Klay (Brookings, 2016).

Note that the publication dates and publishers offered do not necessarily reflect the editions used by Klay in his essay.

Améry, Jean. “At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities” (Indiana University Press, 1980).

Anonymous veteran. “It’s not that I’m lazy” (Harper’s Magazine, October 1946).

Aristotle. “Nicomachean Ethics” (Book III: Chapter VIII).

Bacevich, Andrew. “Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and their Country” (Metropolitan, 2013).

Breckinridge, Henry. “Universal Service as the Basis of National Unity and National Defense” (Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York, July 1, 1916).

Center for Social Development. “The Mission Continues: Engaging post-9/11 Disabled Military Veterans in Civic Service” (August 2011).

Flexner, James T. “George Washington in the American Revolution: 1775-1783” (Hachette, 1968).

Grant, Ulysses S. “Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant” (1885).

Gray, J. Glenn. “The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle” (University of Nebraska Press, 1959)

Hamilton, Alexander. “The Federalist Papers, No. 26” (December 22, 1787).

Hasford, Gustav. “Vietnam Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry” (blog post, June 1987).

Hoy, Pat C., II. “The Beauty and Destructiveness of War: A Literary Portrait of the Vietnam Conflict,” in “Concise Companion to Postwar American Literature and Culture,” Josephine Hendin, ed. (Blackwell Publishing, 2004).

Jarrell, Randall. “Eighth Air Force” (1969).

Jefferson, Thomas. “Letter to Thomas Cooper” (September 10, 1814).

Jünger, Ernst. “Total Mobilisation,” in “”The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader,” Richard Wolin, ed. (MIT Press, 1991).

Levin, Carl. (U.S. Senate Speech, March 14, 2007).

Loring, B.J. “Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution” (1852).

Lovell, Edward J. “The Hessians and the other German auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War” (1884).

Machiavelli, Niccolo. “The Prince (Chapt. XII)” (1532).

Madison, James. “Constitutional Convention Speech” (June 29, 1787).

Mahedy, William. “Out of the Night: The Spiritual Journey of Vietnam Vets” (Greyhound Books, 2005).

Marlantes, Karl. “What it is Like to Go to War” (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2011).

McCullough, David. “1776” (Simon & Schuster, 2006).

Meagher, Robert Emmett. “Killing from the Inside Out: Moral Injury and Just War” (Cascade Books, 2014).

Obama, Barack. “State of the Union Address” (January 12, 2016).

Roosevelt, Theodore. “The Duties of American Citizenship” (speech, January 26, 1883).

Samet, Elizabeth. “No Man’s Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America” (Picador, 2015).

St. Clair, Arthur. In Josiah Harmar Papers.

Vonnegut, Kurt. “Slaughterhouse-Five” (1969).

Washington, George. “General Orders” (August 23, 1776).

—, “Sentiments on a Peace Establishment” (May 2, 1783).

Wood, W.J. “Battles of the Revolutionary War, 1775-1781” (Algonquin Books, 1990).

Commentary

For further reading: Phil Klay’s Brookings Essay reading list

June 3, 2016