More students than ever are going to college in the United States. In 2013, degree-granting higher education institutions in the U.S. enrolled 17.5 million students, which is an increase of more than 45 percent over the last 25 years.

There are a number of reasons that more students are going to more school. While some are continuing their education because it’s expected of them, millions more are doing so because they’ve been told a degree will open doors that would otherwise remain shut.

But beyond our own expectations and beliefs, what does the research tell us about the actual value of a college degree in today’s economy? How does our choice of school or major affect future opportunities? And how do we know whether a degree will pay off five, ten, or fifty years down the road?

If you’re one of the millions of students applying to college for admission next year—or if you’re the parent of a student who is—here are some questions that Brookings research might help you answer:

Do all degrees offer a good return on investment?

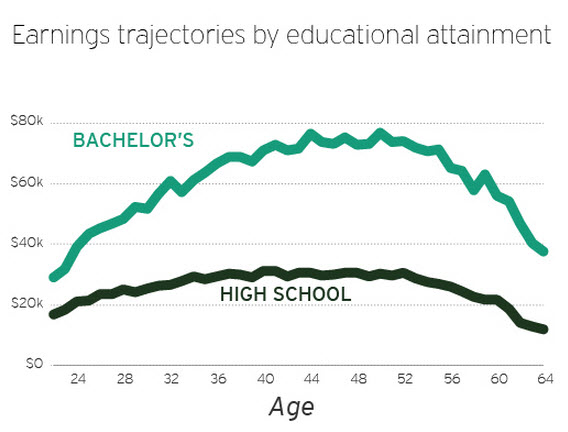

Isabel Sawhill and Stephanie Owen explored this question by looking at research on the average return-on-investment (ROI) students can expect from earning a four-year degree. To perform their analysis, the authors examine research on expected monetary returns, in terms of earnings, while acknowledging there are many non-monetary benefits of attending college.

“On average,” the authors write, “the benefits of a [four-year] college degree far outweigh the costs. Looking at lifetime earnings, the total wage premium for a bachelor’s degree is $570,000.”

However, there’s a lot of nuance behind the average calculation. Many factors influence the ROI of a college degree, and there are certain scenarios where earning a degree might not be as good an investment.

Here are a few key points from the research:

- More selective schools—public or private—offer higher returns.

People who attended the most selective private schools have a lifetime earnings premium of over $620,000 (in 2012 dollars). For those who attended a minimally selective or open admission private school, the premium is only a third of that. - Public schools tend to have higher ROI than private schools, even when comparing selective public schools to selective private schools.

For example, the average ROI for the most competitive public schools in 2010 was around 13 percent. The ROI for the most competitive private schools was around 11 percent. - Post-college earnings vary drastically by college major.

Unsurprisingly, majors in STEM fields have the highest lifetime earnings. -

Graduating on time matters.

While accruing too much debt can hugely impact ROI, fewer than 60 percent of students who enter four-year schools finish within six years. Most selective schools have higher graduation rates. - Financial aid can make a big difference in ROI.

Vassar College, for example, was one of the most expensive schools in the data examined by Sawhill and Owen. The school’s ROI was 6 percent before factoring in its generous financial aid packages (nearly 60 percent of Vassar students receive aid). With financial aid factored in, ROI increased by 50 percent to a total ROI of nine percent.

Learn more about the ROI of four-year degrees by reading “Should Everyone Go to College” from Isabel Sawhill and Stephanie Owen.

What do we know about the value of specific colleges and universities?

Quite a bit, actually, thanks to these new rankings from Jonathan Rothwell and Siddharth Kulkarni.

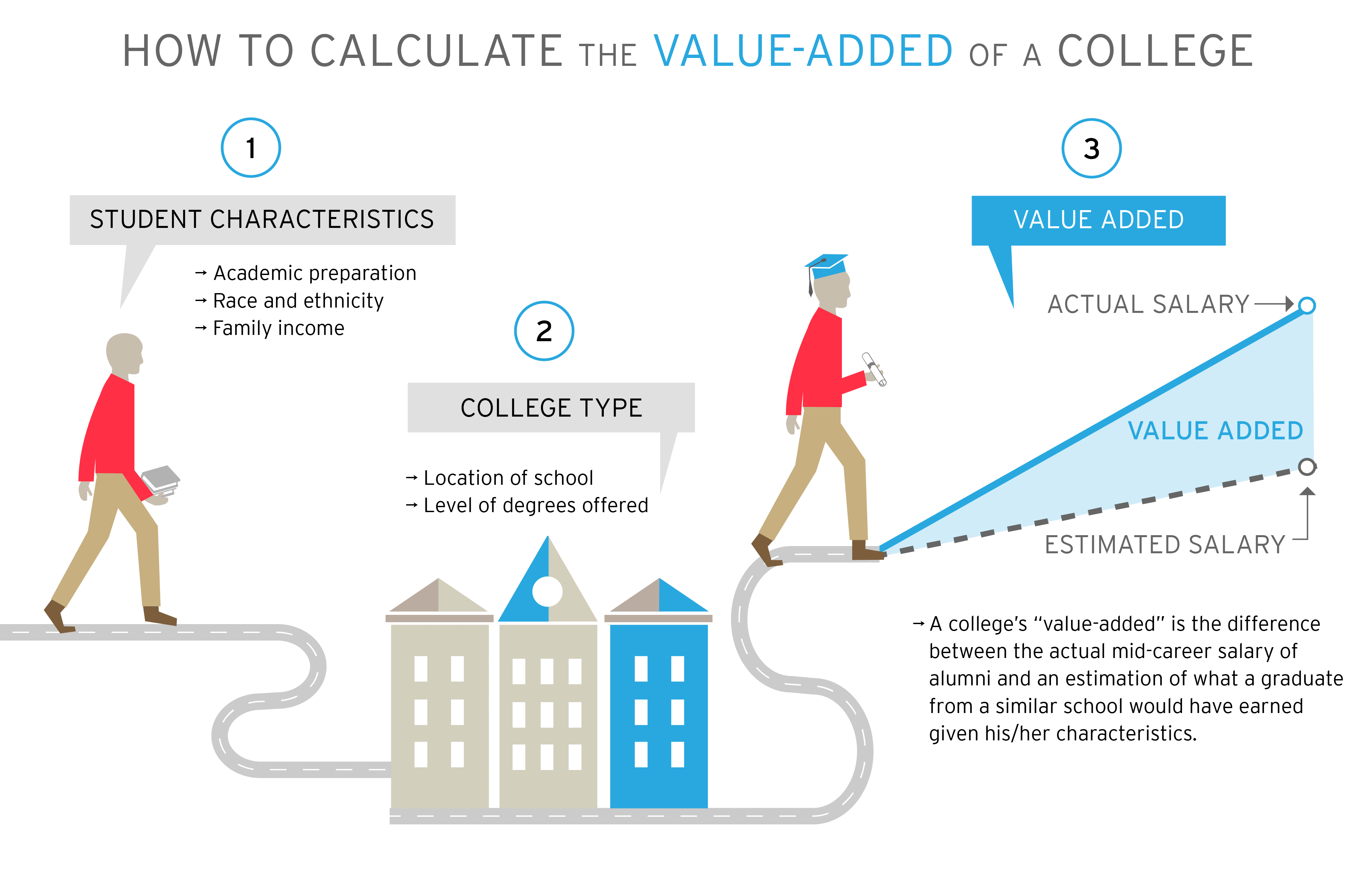

Unlike traditional college rankings, based largely on reputational surveys and assorted admissions data, these rankings calculate the economic “value-added” of two- and four-year colleges. That is, they rank schools by looking at how much more graduates of that school earn and comparing it to their estimated earnings had they graduated from another similar school.

You can search for a school here to see its value-added ranking.

Which schools rise to the top? Cal Tech and Colgate University take the number one and two spots for four-year colleges, and you can find the complete top ten list here.

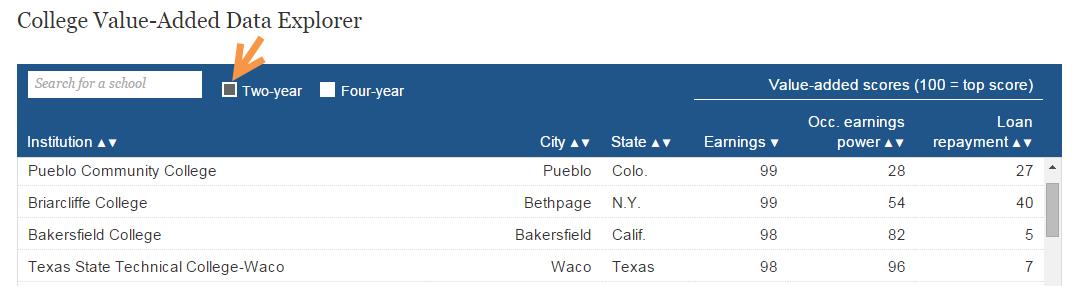

What about two-year colleges?

Rothwell’s rankings include data on two-year schools, as well. If you’re considering higher education options to earn more than a high school degree, but not a four-year bachelor’s degree, you can use the interactive to toggle between two- and four-year schools.

It’s also important to know that if you’re considering starting school at a community college, and later transferring to a four-year institution, you’re definitely not alone. According to Adela Soliz, almost half of four-year undergraduates in the U.S. start at a community college. The popularity of community colleges is one reason President Obama has proposed to make community college free for anyone that can maintain a 2.5 GPA, enroll at least half time, and make “steady progress.”

Soliz is working on several projects to address the importance of simplifying currently complex paths for transferring from community colleges to four-year schools. If you’re looking into community college, you should look up your state’s “transfer and articulation agreement,” which is an agreement that attempts to clarify what courses you’ll need in order to transfer credits.

To learn more, listen to Adela Soliz discuss her research on the Brookings Cafeteria podcast.

How big of a problem will student debt be?

Here’s a shocking fact: About half of all first-year college students in the U.S. seriously underestimate how much student debt they’ve accrued. That’s from a recent study on borrowing habits of college students by Beth Akers and Matthew Chingos.

Because the cost of school greatly influences the ROI of your degree, paying attention to varying costs of schools is critical to ensuring your investment pays off.

So how much debt should you expect to accrue, and how much is too much?

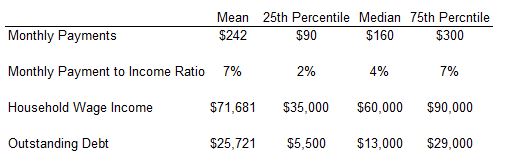

Akers and Chingos have researched the topic heavily, and their findings often come as a surprise to many of us exposed to the popular narrative that America’s college students are being crushed under obscene amounts of student debt.

Contrary to popular belief, Akers and Chingos found that very large loan balances are actually quite rare. In 2010, seven percent of households with debt had balances that exceeded $50,000 and only two percent had balances over $100,000.

According to the Akers’s calculations in her examination of typical households with student debt in 2010, the average household with student debt had a household income of $71,681 and was making a monthly payment toward their loan of $242. That monthly payment is about what those same households spent each month on entertainment ($217) and apparel ($145).

None of this means students shouldn’t pay attention to how much their degree will cost. In 2010, the average debt for households with some debt was about $25,700—and that’s still a lot of money. Furthermore, while the research shows that a college degree often does pay off in the long-term, unemployment among younger graduates and lower wages at the start of their careers mean the short-term benefits of an expensive degree are often difficult to discern.

Who is at risk for borrowing and defaulting?

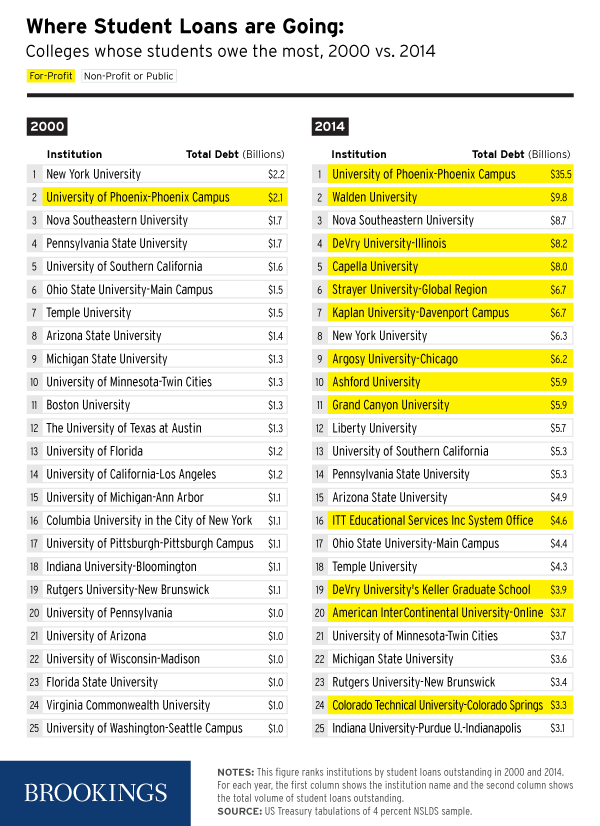

Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis recently made waves with a surprising discovery about which schools’ students have the most debt and are more likely to default on their loans. In a new study published in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity the authors examined debt held by four million student loan borrowers since 1970 and found that the recent increase in student loan delinquency and default can largely be attributed to students who attend for-profit institutions or community colleges.

Of students who entered higher education during the recession, were required to start repaying their loans by 2011, and defaulted within two years, one in five attended a for-profit or two-year college. Only eight percent went to a four-year college. In fact, while half of borrowers repaying their loans by 2011 attended a for-profit school or two-year college, those same borrowers accounted for 70 percent of defaults.

Students who went to for-profit schools or community colleges tended to borrow less, individually, but they also fared poorly in the job market when compared to students from four-year colleges.

So what does this mean? It means you should think carefully about what type of school you choose to attend and aim to earn a degree that you have reason to believe will help you pay back what you borrowed.

Looney and Yannelis did find one bit of good news, though: high default rates among graduates of for-profit schools don’t necessarily reflect future trends. The economy is improving and more graduates are entering the job market, therefore decreasing the likelihood that so many students will continue to default on student loans.

Important factors in your decision

Whether you’re looking into two- or four-year colleges, the good news is there’s a lot of information out there—from Brookings and elsewhere—to help you make an informed decision about your future.

College costs, financial aid packages, degree offerings, and success of previous graduating classes are all factors worth considering as you conduct your search.

Commentary

What to think about when applying to college

August 27, 2015