In the nearly 50 years since its creation, about 80 million American children have watched Sesame Street. For many Americans, Jim Henson’s Muppets are iconic cultural figures that trigger childhood nostalgia.

What many Americans might not associate with Sesame Street, however, are the rigorous standards for research and evaluation that continue to shape the show’s educational programming. Because each lesson is crafted with the input of experts in early education, you probably learned more from those Bert and Ernie sing-alongs than you ever realized.

In a new study on how exposure to Sesame Street affects children’s educational performance, Brookings Senior Fellow Melissa Kearney and Wellesley College’s Phillip Levine find that children living in places where the broadcast signal for Sesame Street was strong were 14 percent less likely to be behind in school compared to children living in places with a weak signal reception.

The research has implications for the ongoing debate over methods for expanding access to early childhood education. Because Sesame Street boasts an extremely low cost-per-child—Kearney and Levine quote one estimate that prices the show’s production at $5 per child, per year—the show could be a readily affordable and scalable intervention.

Sesame Street: Early education by MOOC

“In essence,” Kearney and Levine write, “Sesame Street was the first MOOC.” MOOCs—or Massive Open Online Courses—have grown in popularity over the last several years as new technologies have enabled the transmission of educational programming, courses, and material to students around the world at a low cost.

Today, most MOOCs cater to students in higher education, for example Stanford University’s Stanford Online initiative. Still, the authors hope their analysis can speak to the benefits of MOOCs for many educational purposes and levels.

Sesame Street’s roots in experimental psychology and early education curriculum

Originally dreamed up in the mid-1960s, Sesame Street was made possible by through a collaboration between television producer Joan Ganz and a psychologist named Lloyd Morrisett.

As a PhD student at Yale, Morrisett studied experimental psychology. Later, at the Carnegie Corporation, he created the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the only nationally representative assessment of what America’s students know and can do in various subjects.

However it was Morrisett’s three year-old daughter, and her fascination with television jingles, that first inspired Morrisett to question the potential for television to transfer lasting knowledge to America’s youth.

From the start, strategic research and evaluation were integral to the development of the show’s programming. When Ganz and Morrisett joined forces to create Sesame Street in 1969, they even hired a few Harvard professors to design the show’s curriculum and establish high standards for evaluating its success.

Measuring Sesame Street’s impact

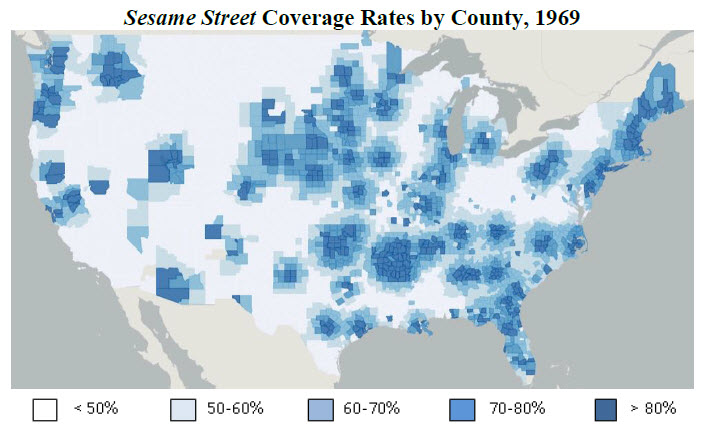

When Sesame Street began in 1969, only two-thirds of U.S. households were able to receive the signal broadcasting the show. While limited access to the show was unfortunate for those children not able to spend their afternoons with Big Bird, the gap in viewership made it possible to measure the show’s impact.

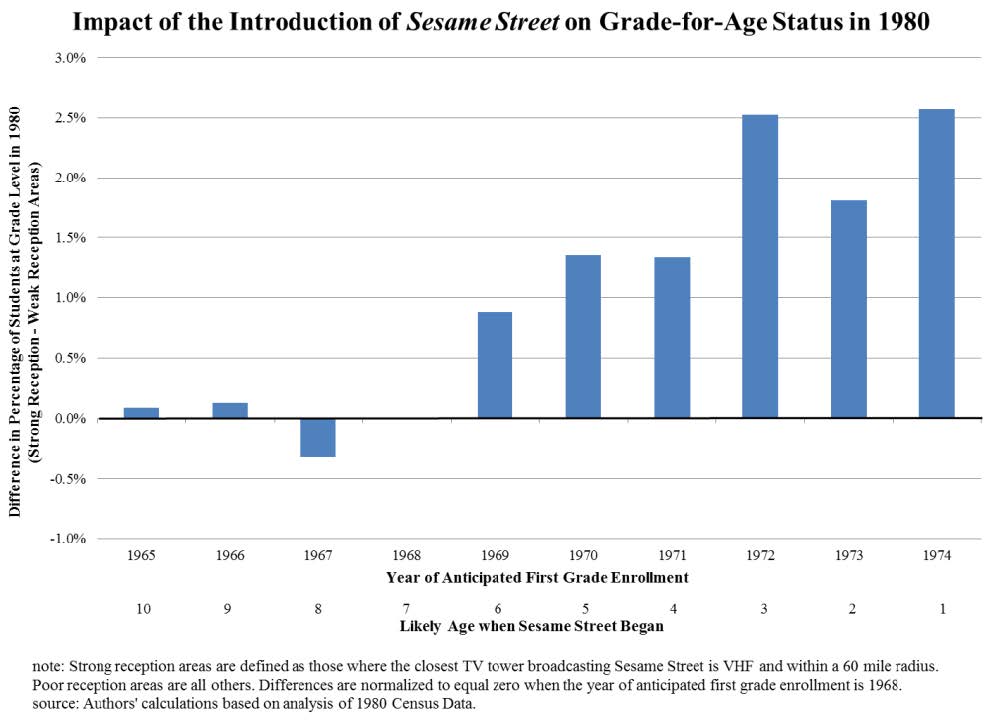

Kearney and Levine first investigated whether children under six living in places where they could easily watch Sesame Street were more prepared for school than slightly older children in those areas that weren’t exposed to Sesame Street. Then, using the gap in viewership, they compared any improvement in educational performance among children under six to those over six with that of children unable to watch the show.

The data show that Sesame Street helps students

Kearney and Levine found significant improvements in grade-for-age status among children under six with access to Sesame Street. Preschool age children living in counties with good access to the show were 1.5 to 2.0 percent more likely to remain at the appropriate grade throughout their school years. That positive effect was particularly pronounced for boys, black non-Hispanic children, and those living in economically disadvantaged areas.

When looking at preschool age children in strong and weak reception areas, the impact of the show’s introduction was greater among children from economically disadvantaged areas.

Overall, moving from a weak to strong reception county reduced the likelihood of falling behind the appropriate grade level by approximately 14 percent.

Of their findings, Kearney and Levin write, “This is impressive, but perhaps even more so given the extremely low per-child costs of airing the program…In light of all the emphasis on the importance of early childhood interventions, the fact that a television show can have this type of an effect should be taken as very good news.”

Can the Sesame Street model be replicated for older students?

According to Kearney and Levine, advocates for new models of higher education should take note and revisit their roots. If Sesame Street can teach a generation to count, what can intelligently-designed MOOCs do for the world’s college students?

Kearney and Levine acknowledge that, outside their study on Sesame Street’s success, there’s been little research into the ability of MOOCs to improve outcomes for participants. “Any proper evaluation of the impact of electronic transmission of educational content is beneficial.”

For those of who first learned the alphabet from the crew on Sesame Street, it would be hard not to agree.

RELATED CONTENT:

Commentary

Sesame Street was the original MOOC

June 18, 2015