On Thursday, the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings hosted a discussion with leading experts on the most important challenges the continent faces in 2015. The event marked the official launch of AGI’s annual report, “Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2015.”

Below are highlights of the discussion, featuring a question posed to each panelist by event moderator Shaka Ssali, host of “Straight Talk Africa,” who also invited the online and in-person audience to answer the same questions in live polling. AGI experts will comment on the poll results in a forthcoming post.

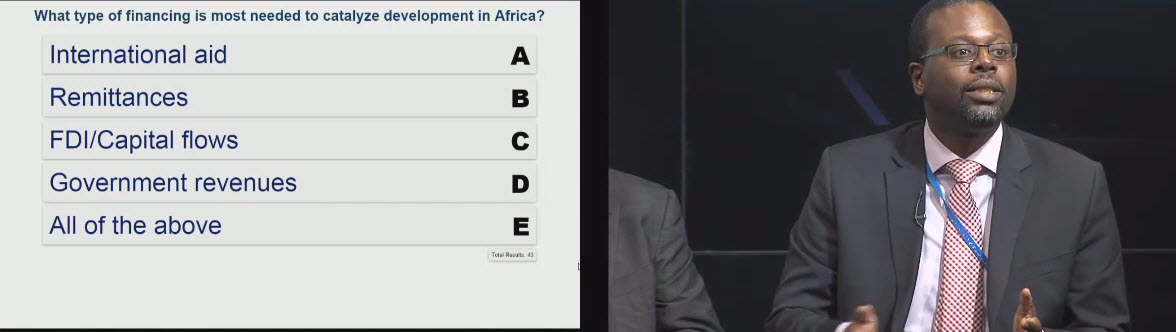

What type of financing is most needed to catalyze development in Africa?

Amadou Sy, director of the Africa Growth Initiative, posed two key questions: How do we get more financing? And, how do we get better financing?

“When it comes to more financing,” Sy said, “Africa has really got more external financing. Over the past 20 years, for example, foreign direct investment has been multiplied 30 times. So we’ve been receiving much more private capital. When it comes to aid, unfortunately the promises of Gleneagles have not been really fulfilled. So aid is on a downward trend.”

Plus, he argued, while “private capital flows and remittances on an upward trend,” we “have to be careful” because the money is going to a very few sectors, such as natural resources.

Concerning “better financing,” Sy noted that many countries are avoiding financing flows that are considered volatile, instead favoring long term financing. Still, since 2006, $15 billion in Eurobonds have been issued by African countries.

Sy emphasized a few key questions:

- How does the money really benefit development?

- How does the money really lead to increasing jobs?

- How can the money we get really lead to Africa better fulfilling its development objectives?

- How does Africa insert itself into this global value chain?

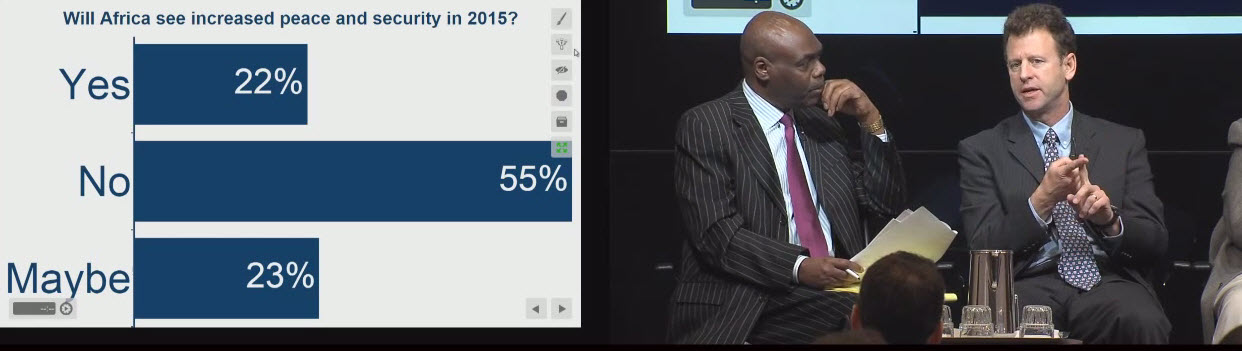

Will Africa see increased peace and security in 2015?

Senior Fellow Michael O’Hanlon, director of research in Foreign Policy and the Sydney Stein, Jr. Chair in International Security, broke the question down into three categories of violence—terrorism, civil war, and crime—and then by region.

On terrorism, he said “trends are not good” (though with regional variations) and “Exhibit A on why we have to worry” is Boko Haram in Nigeria. He called civil war “a mixed picture,” with progress in some places and “backsliding or failure to take the next step in places like Sudan.” O’Hanlon also observed that Nigeria is “prone to civil warfare.” There is a slightly positive note: The state of civil war in Africa is “a little better in this decade than they have often been in previous decades.” Importantly, O’Hanlon said crime, which he called “the silent scourge in much of Africa,” “is the issue we don’t talk about enough and African governments need help strengthening their internal ability to control crime.” While there is gradual progress in addressing the lack of economic opportunity, underdevelopment, poor education and other conditions that reinforce crime, “I don’t think we’re doing enough,” he said.

Regionally, O’Hanlon characterized the Horn of Africa (despite the tragedy in Kenya), as “a little better” because of recent successes in curbing al-Shabab: “Somalia ironically is one of the good news stories.” Central northern Africa “doesn’t look better as we had hoped,” he said, due to the “disappointment” of Sudan and South Sudan. In western Africa, O’Hanlon noted his biggest worry: “It is all about Nigeria,” the “giant of west Africa.” Regarding another hot spot, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, O’Hanlon called the central government in Kinshasa “still weak and not necessarily distinguishing itself as a legitimate and truly unifying force in the country.” Finally, on southern Africa, O’Hanlon noted the good news that there is not a lot of terrorism or civil warfare, “but unfortunately there is still plenty of crime.”

Rate the national and international response to the Ebola crisis

Nonresident Senior Fellow Vera Songwe discussed the national and international responses to the Ebola crisis emphasizing that the national and international responses should not be rated the same. “In countries where we saw the Ebola virus quickly contained,” she observed, “we got a lot of leadership.” She pointed to good leadership, governance, and communication in Senegal, Nigeria, and Uganda (in a past outbreak). But in Guinea, for example, she explained that the virus hit rural areas that did not have the educational framework to quickly contain it. The private sector and civil society, too, played important roles in countries like Senegal to contain the spread of disease. “This is one of the first cases,” she said, “where the responses in terms of the private sector and capital flows into Africa begins to link up—we see logistics working, we see private sector working, we see [information and communications technology] and information working. So at that national level I think things worked quite well.”

Songwe noted two issues with the international response: Who was going to be first responder and what was the coordinating mechanism? “This was where the international response was maybe slow to act,” she said. While the World Health Organization is the repository of the technical and medical protocols, the IMF and World Bank would respond from the financial side. Plus, the international community, including the United States, made financial commitments. “How do you collect those resources,” she asked. “There is no international emergency response resource institution.”

Although “at the international level the coordination was slow to come,” she said, “there is now a concerted, coordinated effort around [it].”

How is the African Union doing?

Senior Fellow Mwangi Kimenyi, former director of the Africa Growth Initiative, called the AU a “very important institution” that “I would like to see succeed.” He cited the fact that African economies are small, and that Africa “has a very small voice globally.” So, “this tells us that we need to think about working together as a continent, having an institution that can represent all the countries,” Kimenyi added. The AU is also very important, he said, in terms of coordinating security and regional integration.

However, “what we need to do for an imagined continent,” he said, “is that we really need to reform the AU.” Kimenyi cited a few cases where the AU could do better, such as coordinating the response to Ebola, leading peacekeeping in places like Central African Republic (where France took the lead), and reforming the AU’s leadership, which is currently rotational and allowed anti-democratic leaders to take the helm.

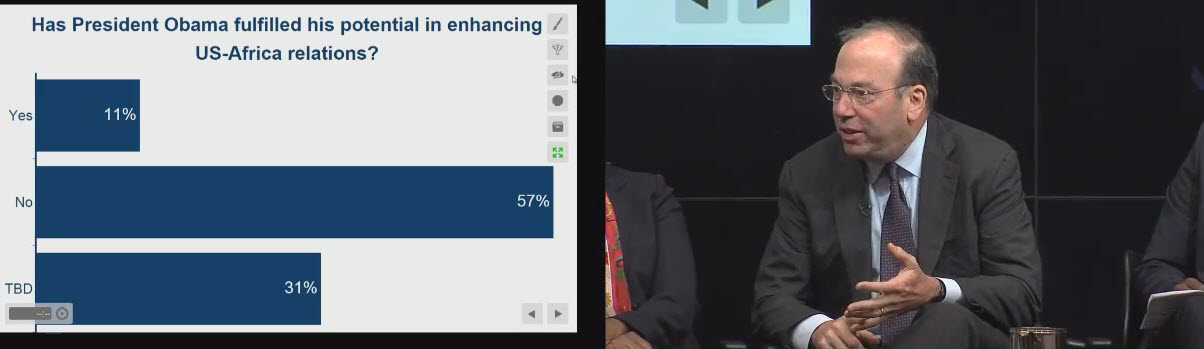

Has President Obama fulfilled his potential in harnessing U.S.-Africa relations?

Nonresident Senior Fellow Witney Schneidman characterized President Obama’s legacy as “still very much a work in progress.” While he “raised expectations quite significantly” by visiting Ghana very early in his administration, Schneidman said, “that was sort of it for the next four years” as the president dealt with an economic crisis at home, unwinding from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and political heat at home. Then, Schneidman explained, President Obama’s 2013 trip to Africa produced three initiatives: Power Africa; Trade Africa; and the Young African Leaders Initiative, which he called “probably the most exciting initiative which is focused on engaging Africa’s next generation of leaders.”

These three plus the Feed the Future program launched in 2009, Schneidman said, have all featured the private sector from the beginning, “so no longer are we treating Africa as this strange market that you might want to invest in.” The Obama administration, he said, “has done a good job of working with the U.S. private sector to put this issue at the forefront,” an approach exemplified by the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in 2014.

Despite this progress, Schneidman added that “the work in progress is still quite significant.” He cited a number of issues that still need to be addressed, including:

- the critical importance of extending AGOA, which if it expires in September 2015 would “be a big setback for U.S.-Africa commercial engagement”;

- competition from the European Union, which has signed economic partnership agreements with 33 African countries that “will put U.S. companies at a serious commercial disadvantage once they come into force”;

- the EU’s free trade agreement with South Africa “that’s already putting U.S. companies at a serious disadvantage”;

- security, including the Bush administration’s inadequately coordinated rollout of Africom and the Obama administration’s “missed opportunity” to have a security dialogue with heads of state and ministers of defense; and

- following up to the Africa Leaders Summit.

Visit the event’s web page for a full webcast archive or watch it below, plus get more details about the event, and links to related research, including the new report, “Foresight Africa: Top Priorities for the Continent in 2015.”

Commentary

Experts Talk Top Priorities for Africa in 2015

January 16, 2015