“Our analysis of more than two decades of data on the financial well-being of American households suggests that the reality of student loans may not be as dire as many commentators fear,” write Beth Akers and Matt Chingos in their new paper, released in June, exploring the causes of, consequences of, and solutions for rising student loan debt burdens.

In May, scholars from Economic Studies at Brookings and the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) observed that “borrowing to finance higher education has increased markedly over the past two decades. These trends are associated with a variety of negative economic outcomes for households who hold the debt, but those outcomes must be weighed against the net increase in earnings the households receive from acquiring more education.”

The two papers and additional research demonstrate a more complex, but less dire, situation than commonly portrayed in the media. Here are some facts about student loans that inform discussion of the issue and the policy options (with notations to their source materials, below).

The Volume and Share of Student Loans Is Growing

- U.S. student loan balances exceeded $1.2 trillion as of 2013. (TPC)

- The overall percentage of households with outstanding student loan debt grew from 9 percent in 1989 to 19 percent in 2010. (TPC)

- The share of “young households” (where the average age of adults is 20 to 40) with education debt rose from 14 percent in 1989 to 36 percent in 2010. (Akers/Chingos)

- The median debt outstanding among households with student loans has risen from about $5,200 in 1989 to $13,400 in 2010. (TPC)

- The median debt among young households grew from $3,517 in 1989 to $8,500 in 2010. (Akers/Chingos)

The Distribution of Debt by Volume and Household Type Varies

- In 2010, only 7 percent of young households with student debt owed more than $50,000, and 2 percent owed more than $100,000. Nearly three-quarters owed less than $20,000. (Akers/Chingos)

- In 2010, among all households with outstanding student loan debt the average balance was $25,700. (Akers)

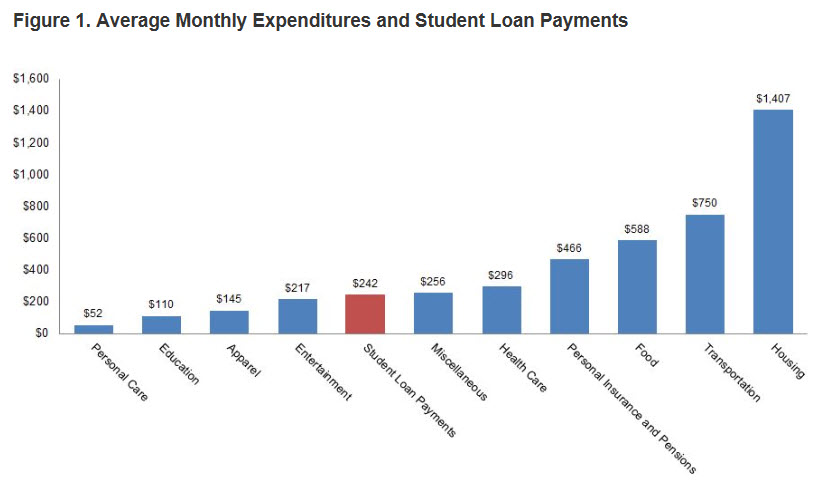

- The median household with student debt devoted 4 percent of its monthly earnings to loan repayment, comparable to average spending on entertainment and clothing. (Akers)

(Source: Calculations by Elizabeth Akers with 2010 Survey of Consumer Finance and 2012 Consumer Expenditure Survey)

A Variety of Reasons Why Student Loan Debt Has Increased

Akers and Chingos posit three possible reasons: increased college tuition; students are paying less out-of-pocket and relying more on loans to finance college; and rising educational attainment. Akers, Chingos and the authors of the TPC report also point to an increase in college enrollment. Between 2002 and 2011, college enrollment increased 27 percent (Gale/Harris)

- The change in educational attainment, according to Chingos and Akers, accounts for (statistically) about a quarter of the change in debt levels. (Akers/Chingos)

- The TPC authors conclude that higher enrollment and higher costs can explain 60 percent of the increase in aggregate loan volume from 2002 to 2011. (TPC)

- Between 1962 and 2011, the inflation-adjusted cost of attending a public college has increased from about $7,000 to more than $17,000, reflecting diminishing taxpayer support for college attendance. (Gale/Harris)

- According to the Hamilton Project, however, the average net tuition increase for public and private four-year colleges has increased only 13 percent from 2002-2013. (The Hamilton Project)

- Households with a graduate degree had an increase of 311 percent in education debt, with the average debt rising from about $10,000 to over $40,000. (Akers/Chingos)

Akers and Chingos note that “The growth in student loan debt is often discussed as a problem in and of itself. However, to the extent that borrowers are using debt as a tool to finance investments in human capital that pay off through higher wages in the future, increases in debt may simply be a benign symptom of increasing expenditure on higher education.”

The TPC paper authors emphasize that: “Student loan debt represents debt undertaken to finance an investment in human capital. Simply comparing the financial and economic circumstances of households with and without student debt can be misleading if it does not also account for the additional earnings capacity produced by the education that was financed by that debt.”

“We need to rethink the proposition that more student loan debt leads to greater financial hardship,” Akers wrote in a separate post. “The answer to the systemic problems in student lending is not to discourage borrowing. Rather, we should focus on propagating the idea that loans are a valuable tool for raising future earnings when they are used appropriately.”

To learn more about Brookings research on student loan issues, see:

“Is a Student Loan Crisis on the Horizon?” by Beth Akers and Matthew M. Chingos

“Student Loans Rising,” by William Gale, Benjamin Harris, Bryant Renaud and Katherine Rodihan

“Should Taxpayers Rescue Debt-stressed College Grads?” by William Gale and Benjamin Harris

“Rising Student Debt Burdens: Factors Behind the Phenomenon,” The Hamilton Project

“The Typical Household with Student Loan Debt,” by Beth Akers

“Reconsidering the Conventional Wisdom on Student Loan Debt and Home Ownership,” by Beth Akers

“Loans for Educational Opportunity: Making Borrowing Work for Today’s Students,” by Susan Dynarski and Daniel Kreisman

“Moving on to the Real Issues in Student Lending,” by Beth Akers

Commentary

These Facts about Student Loans Might Surprise You

July 8, 2014