Despite my years of research experience on African industrial development, it has come to my attention for the first time that there has been a long tradition of celebrating Africa Industrialization Day on November 20—each year since 1990! But why celebrate African industrialization? In short, to raise global awareness on the importance and challenges of African industrialization and to stimulate the international community’s commitment to the industrialization of Africa. In addition, African industrial development contributes to not just overall economic and social development but also to this year’s theme: Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) for poverty eradication and job creation for women and youth.

1.

Why do we care about African industrialization?

All countries should have an active industrial policy to achieve sustainable development: Sound industrial policies present Africa opportunities to invest in its human and physical capital formation, in technological innovation, and in supportive institutions. In addition to the merits of industrialization on its own, African industrialization also helps countries achieve pro-poor growth and safeguards economies against market and climate-related shocks. Thus, African industrialization is essential to spurring growth and improving overall well-being on the continent.

2.

What is the state of African industrial sector?

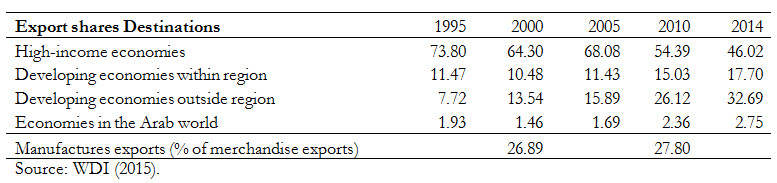

The industrial sector, however, is not yet the main driver of most African economies. According to WDI (2015), only 11 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP came from the manufacturing sector in 2014, after a decline from where it was in year 2000 (13 percent). The service sector, on the other hand, has seen an increase of nearly 10 percentage points (from just under 50 percent in 2000 to 58 percent in 2014). The industrial sector is not a major employer either, with the majority of the labor force employed in the agricultural sector. A small domestic market, and lack of access and capability to compete in the international market has kept the region’s market for industrial products limited. In 2010, only 2 percent of world’s merchandise exports were from sub-Saharan Africa. Of that small share of the region’s total merchandise exports, just 28 percent came from the manufacturing sector (compared to a world average of 67 percent). Disaggregating total merchandise exports by export destinations reveals that over the past decade the share of sub-Saharan Africa’s merchandise exports have started to shift from high-income countries to destinations in developing countries.

Table 1. Sub-Saharan Africa’s Exports by Destinations (% of total merchandise exports)

Leaving these macro figures aside and looking into the sector through a micro lens reveals that a typical business in Africa is small, employing a few workers besides the owner(s). Notably, SMEs contribute to the major share of employment in the sector while large and more formal firms take a lead on the sector’s contribution to gross domestic product. Women and youth constitute the majority of SMEs in Africa’s formal and informal industrial sectors.

3.

Why is a typical firm in Africa small?

The small size of the domestic market for industrial products partly explains the size distribution of the African industrial sector. Very often SMEs struggle with lack of access to dependable markets due to limited business networks or lack of marketing skills to identify potential markets and to compete with more established large firms. Market failures, such as lack of access to affordable credit and investment uncertainties, also make it a natural starting point for Africa’s entrepreneurs to start small and invest in small steps.

4.

What are the survival and growth prospect of small businesses in Africa?

Unfortunately, small and young firms have the least likelihood of surviving competition regardless of their economic performance. Small businesses charge lower prices for their products for the first three to five years, though it is not obvious that they produce inferior quality products or use less productive technologies. The growth prospects of small startups surviving market selection is not as promising as we want them to be either. It is a highly debated matter whether SMEs take the lead in contributing to job creation in the African industrial sector (Ayyagari et al., 2011; Page and Soderbom, 2012). Central to this debate is the question of whether the total jobs created by SMEs is due to employment growth through expansion of existing firms or due to an influx of small startups that are unlikely to survive market selection a few years down the line.

5.

How do these challenges influence Africa’s industrial development?

The above challenges of small and young enterprises, coupled with high unemployment rates, contribute to the lack of incentives to formalize or start small businesses in Africa’s formal industrial sector. For example, research on Ethiopia’s urban informal sector shows that with the exception of the absolutely small firms, returns to invested capitals are smaller in the informal sector than they are for formal firms with comparable capital stock. Even in the informal sector, the study finds that firms with better access to dependable markets (through marketing linkages with traders and by being part of a value chain network of manufacturers) have better prospects of growth and capacity expansion.

6.

What do we need to do about it?

Industry’s role for job creation and poverty reduction is limited unless we address the survival and growth prospects of Africa’s small businesses. To start, we need market development interventions targeting building marketing skills and capability of domestic firms to identify, network with, and compete in wider and reliable markets. Research shows that the firms that manage to translate market potentials into high profitability are more likely to grow (Banerjee and Duflo, 2011; Siba, 2015). Next, we need to encourage the entry of larger firms by addressing investment uncertainties and by widening the extent of local markets through reduction in transport costs. Following up a large-scale investment in road infrastructure, Shiferaw et al., 2015 find that reduction in transport costs is associated with an increase in average startup size. Finally, we also need to look beyond the domestic market and exploit the benefits of export promotion and regional integration to widen the market destination of Africa’s industrial products.

I hope the state of research on Africa’s industrial development has contributed to today’s cause in making it clear that we need more jobs—and many more good jobs—for Africa’s industries to meaningfully contribute to job creation and poverty reduction.

Commentary

Africa Industrialization Day through the micro lens

November 20, 2015