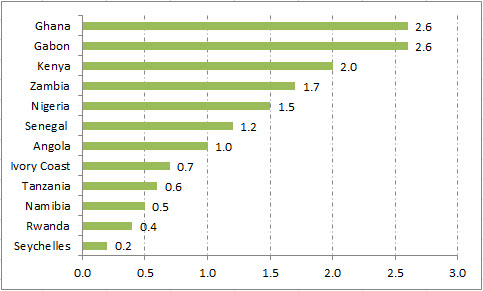

Before 2006, only South Africa had issued a sovereign bond in sub-Saharan Africa. Since then, 12 other countries have issued a total of $15 billion in sovereign bonds compared to South Africa’s $10.9 billion. Including South Africa, sub-Saharan sovereigns issued $7 billion of foreign-currency denominated bonds in 2014 alone.

Figure 1. Sub-Saharan Africa (ex. South Africa): Cumulative Sovereign Bond Issuance, 2006-2014 (in US$ Billions)

Source: Dealogic.

The entry of sub-Saharan African economies into sovereign debt markets has generated a lot of excitement among foreign investors who are keen on seizing upon the continent’s favorable growth outlook. Whether the rash of borrowing by sub-Saharan African governments (as well as a handful of corporate entities in the region) is sustainable over the medium-to-long term, however, is open to question. One way of considering this issue of sustainability is by analyzing the risk of external debt distress and fiscal positions of these countries in the context of the current global financial landscape.

Debt Sustainability Is Not the Immediate Concern

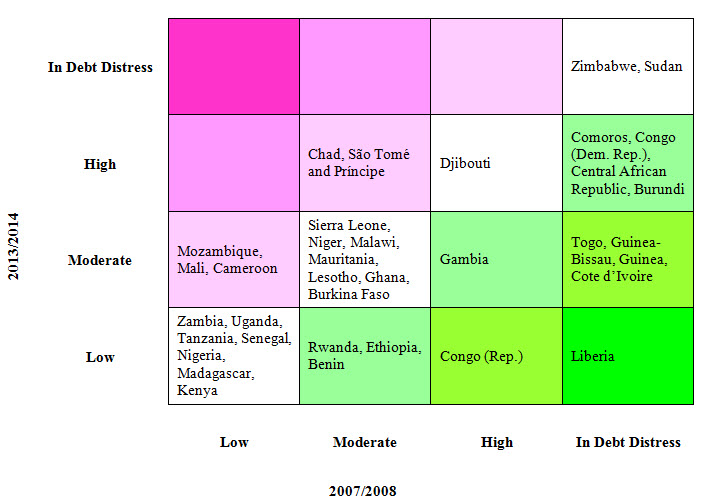

A debt sustainability analysis of the poorest sub-Saharan African countries indicates that the risk of external debt distress from adverse changes to global financial conditions is low or moderate for most sovereign issuers (Table 1). So, barring major exchange rate shocks or adjustments to external financing terms, most issuing sovereigns are expected to meet their debt obligations. Since 2007-2008 the risk of external debt distress has fallen for Rwanda and Côte d’Ivoire (from moderate to low-risk, and “in distress” to moderate risk, respectively). The levels of risk have remained unchanged for Ghana (classified as moderate risk) as well as Nigeria, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia (categorized as low risk).

Table 1. Low-Income Developing Countries: Changes in Risk Rating for External Distress

Source: IMF 2014 LIDC Report, DSAs.

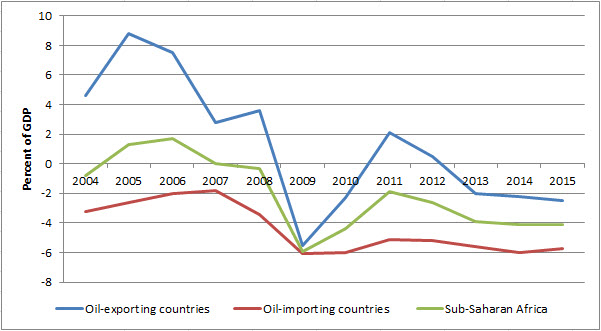

But Fiscal Risks Are Rising

While the risk of external debt distress appears manageable, fiscal sustainability is proving to be challenging for many countries (Figure 2). While oil-importing economies have typically lower overall fiscal balances due to higher expenditures on oil such as subsidies on fuel products, lower oil prices will have a negative impact on oil-exporting countries as their surpluses are sharply reduced. In addition, many countries are increasing current spending (on the provision of goods and services) to meet their urgent development needs following decades of structural adjustment, while others are stepping up capital spending (on more durable assets) to meet their infrastructure needs without compensating for these additional expenses through commensurate increases in revenues. Thus, insufficient resource mobilization is deteriorating these countries’ fiscal positions.

Figure 2. Sub-Saharan Africa: Overall Fiscal Balance, Excluding Grants

Source: IMF.

External Risks, Including Oil Price Risk, Are Rising

Recent trends and developments indicate that external push factors are becoming less favorable to sub-Saharan African countries. First, the record-low interest rates that prevail in the United States are set to increase, meaning that countries will have to start allocating larger proportions of their budgets toward paying interest, while paying off less of their debt. Second, risk appetites of foreign investors, although they remain high, may fall when global interest rates increase and growth rates decline. Third, the price of crude oil has fallen by 27 percent since July 2014 and has broken $80 a barrel for the first time since mid-2012. As a result, sub-Saharan African countries will face a higher cost of borrowing. While new issuers will have more flexibility about the timing of their debt issuance as market conditions become more challenging, recent issuers will have to pay higher refinancing costs when their bonds mature.

Oil Producers and Countries with Weak Fiscal Situations Are Becoming More Vulnerable

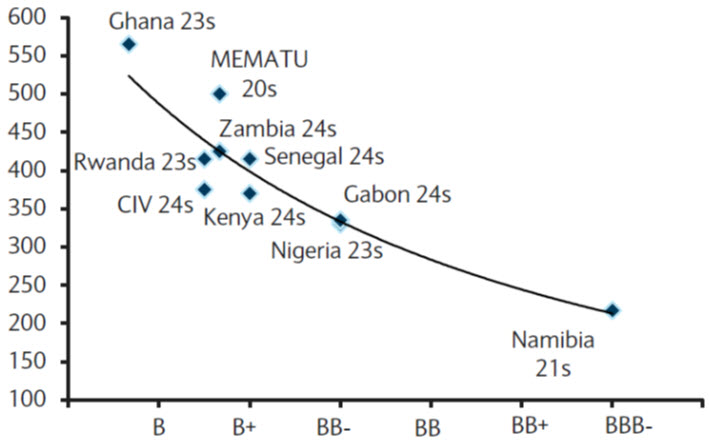

If we take, for example, Ghana, we see that it has been able to retain international sovereign bond market access but at the cost of increased cost of borrowing, as its economic performance has worsened. Ghana has been plagued by the “twin deficits” of fiscal and current account deficits (Figure 3). Higher salaries for public officials and lower gold and cocoa (and now oil) prices have led the government to spend more than it collects in terms of revenues. The country has also been importing more than it exports, causing a trade deficit and exacerbating the current account deficit. This situation cannot be sustained for long as it creates major macroeconomic imbalances. In September 2014, Ghana raised $1 billion for a 12-year bond paying a coupon of 8.125 percent at the same time it was negotiating an IMF program. However, Ghana is now paying the highest spread among sub-Saharan issuers at about 550 basis points (or 5.50 percent) over U.S. Treasury bonds (Figure 3) and has the lowest credit rating.

Oil producers will also face less favorable market conditions as their fundamentals deteriorate due to the fall in oil prices. Among sovereign issuers, Barclays (2014) estimates that a drop of $10 per barrel in oil prices would lead to a net export loss of $6.1 billion for Nigeria and $5.7 billion for Angola, thereby eroding their current account surpluses. The dependence on oil exports and revenues in these countries and other oil-exporting countries is relatively high: Oil exports make up 95 percent of total exports and over 70 percent of fiscal revenues for both Nigeria and Angola, while in Gabon oil accounts for over 80 percent of country’s exports and 60 percent of government revenues.

Figure 3. Sub-Saharan Africa: Sovereign Spreads and Credit Ratings

(in Basis Points as of October 28, 2014)

Source: Bloomberg L.P. and Barclays Research

Improving fiscal policy should be a priority for African countries gaining international sovereign bond market access, especially when their fundamentals are deteriorating. A recent blog by Moreno-Badia and Presbitero (2014) recommends improvements in several areas, including (i) stronger budgetary institutions; (ii) raising more revenues from countries’ own tax bases; (iii) improving spending efficiency, especially investment project selection and management; and (iv) comprehensive medium-term debt management strategies. However, many of these recommendations take time, and policymakers should start with “low-hanging fruit.” For example, reforming public procurement is a more readily attainable step toward improving project selection and would be a good starting point for many African governments.

Commentary

African Frontier Markets: Debt Ratios Look OK but Fiscal Clouds Loom

November 21, 2014